Estimated Impacts of Final Public Charge Inadmissibility Rule on Immigrants and Medicaid Coverage

Executive Summary

In August 2019, the Trump Administration published a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) final rule to change “public charge” inadmissibility policies. Under longstanding immigration policy, federal officials can deny entry to the U.S. or adjustment to legal permanent resident (LPR) status (i.e., a “green card”) to someone they determine to be a public charge. The new rule redefines public charge and expands the programs that the federal government considers in public charge determinations to include previously excluded health, nutrition, and housing programs, such as Medicaid for non-pregnant adults. It also identifies characteristics DHS will consider as negative factors that increase the likelihood of someone becoming a public charge, including having income below 125% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($26,663 for a family of three as of 2019). The rule is scheduled to go into effect as of October 15, 2019. Using the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 2014 Panel and 2017 American Community Survey (ACS) data, this analysis provides estimates of the rule’s potential impacts:

Nearly eight in ten (79%) noncitizens who originally entered the U.S. without LPR status have at least one characteristic that DHS could weigh negatively in a public charge determination. Over one in four (27%) have a characteristic that DHS could consider a heavily weighted negative factor. The most common negative factors among the population are lacking private health insurance (56%), not having a high school diploma (39%), and having family income below the new 125% FPL threshold (32%).

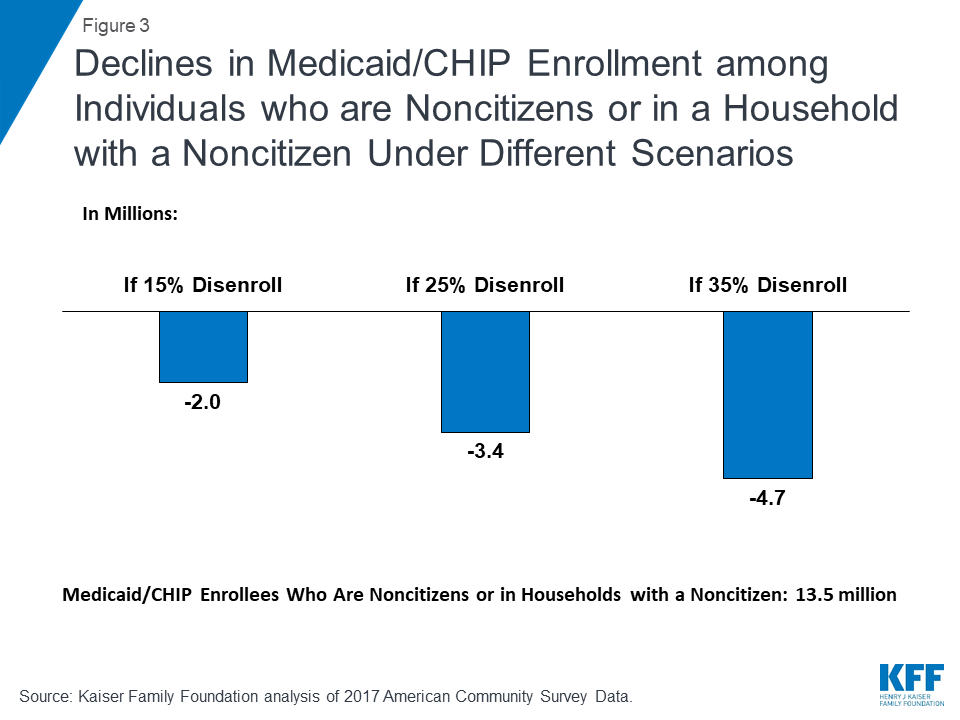

If the rule leads to disenrollment rates ranging from 15% to 35% among Medicaid and CHIP enrollees who are noncitizens or live in a household with a noncitizen, between 2.0 to 4.7 million individuals could disenroll. Previous research and recent experience suggest that the rule will likely lead to decreased enrollment in public programs among immigrant families beyond those directly affected by the rule due to fear and confusion about the changes. Even before the rule was finalized, there were reports of parents disenrolling themselves and their children from Medicaid and CHIP coverage, choosing not to renew coverage, or choosing not to enroll despite being eligible. Beyond potential disenrollment, the rule may also deter new enrollment among some of the nearly 1.8 million uninsured individuals who are eligible for Medicaid and CHIP but not enrolled and are noncitizens themselves or live in a household with a noncitizen. Decreased participation in Medicaid would increase the uninsured rate among immigrant families, reducing access to care and contributing to worse health outcomes. Coverage losses also will likely decrease revenues and increase uncompensated care for providers and have spillover effects within communities.

Key Findings

Introduction

In August 2019, the Trump Administration published a DHS final rule to change “public charge” inadmissibility policies. Under longstanding immigration policy, federal officials can deny entry to the U.S. or adjustment to LPR status (i.e., a “green card”) to someone they determine to be a public charge. Based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the SIPP 2014 Panel and 2017 ACS data, this analysis provides updated estimates of the:

- Share of noncitizens who originally entered the U.S. without LPR status who have characteristics that DHS could potentially weigh negatively in a public charge determination; and

- Number of individuals who might disenroll from Medicaid under different scenarios in response to the rule.

Background

Under longstanding policy, if authorities determine that an individual is likely to become a public charge, they may deny that person’s application for LPR status or entry into the U.S.1 Public charge determinations are a forward-looking test in which officials will assess the likelihood of someone becoming a public charge in the future. Specifically, DHS finds an individual “inadmissible” if officials determine that he or she is more likely than not at any time in the future to become a public charge.

The rule redefines public charge and broadens the programs that the federal government will consider in public charge determinations to include previously excluded health, nutrition, and housing programs (Table 1). Under previous policy, a person was considered a public charge if officials determined he or she was likely to become primarily dependent on the federal government as demonstrated by use of cash assistance programs or government-funded institutionalized long-term care. Guidance specifically clarified the exclusion of Medicaid and other non-cash programs from these decisions because of concerns that fears were limiting enrollment of families. Under the new rule, officials will determine someone to be a public charge if they determine an individual is more likely than not at any time in the future to receive one or more public benefits for more than 12 months in the aggregate within any 36-month period (such that, for instance, receipt of two benefits in one month counts as two months). Further, the rule defines public benefits to include federal, state, or local cash benefit programs for income maintenance and certain health, nutrition, and housing programs that were previously excluded from public charge determinations, such as non-emergency Medicaid for non-pregnant adults, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and several housing programs.

| Table 1: Change in Public Charge Definition and Programs Considered | ||

| Previous Policy | Policy Under New Rule | |

| Public Charge Definition | Likely to become primarily dependent on the federal government as demonstrated by use of cash assistance programs or government-funded institutionalized long-term care. | More likely than not at any time in the future to receive one or more public benefits for more than 12 months in the aggregate within any 36-month period (such that, for instance, receipt of two benefits in one month counts as two months). |

| Programs Considered in Public Charge Determinations |

|

|

Officials make public charge determinations based on the totality of the person’s circumstances. At a minimum, officials must take into account an individual’s age; health; family status; assets, resources, and financial status; and education and skills. The rule describes how DHS will consider each factor and identifies characteristics it will deem as positive factors that reduce the likelihood of an individual becoming a public charge and negative factors that increase the likelihood of becoming a public charge. DHS indicates that no single factor would govern a determination, and it appears officials would retain significant discretion in assessing factors and making determinations. The rule establishes a new income standard of 125% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($26,663 for a family of three as of 2019) and specifies that family income below that standard is a negative factor. Some other negative factors include having a lower education level, a health condition, lacking private health insurance, not being employed or a primary caregiver, and having limited English proficiency. Examples of positive factors include being of working age, being in good health, having private health coverage, and having income at or above 125% FPL. The rule also specifies certain heavily weighted negative and positive factors.

The rule identifies previous or current use of public benefits as a negative factor, but most immigrants who would be seeking admission or adjustment to LPR status are already ineligible for these programs or are exempt from a public charge determination. For example, eligibility for the programs included in the rule for immigrants without LPR status is now largely limited to humanitarian immigrants such as refugees and asylees, who are exempt from the public charge test. However, since the public charge determination is a forward-looking test, even if an individual is not currently or has not previously used a public benefit, officials will assess the likelihood of an individual using those benefits in the future.

The new rule will likely lead to decreased enrollment in Medicaid and other programs among individuals in immigrant families beyond those directly affected by the rule, including their primarily U.S.-born children. Although few people directly affected by the rule are enrolled in Medicaid and the other public benefit programs, previous experience and recent research suggest that the rule will have chilling effects that would lead individuals to forgo enrollment in or disenroll themselves and their children from programs due to confusion and fear that their or their children’s enrollment could negatively affect their or another family member’s immigration status.3 For example, prior to the final rule, there were anecdotal reports of individuals disenrolling or choosing not to enroll themselves or their children in Medicaid and CHIP due to fears and uncertainty.4 Providers also reported increasing concerns among parents about enrolling their children in Medicaid and food assistance programs,5 and WIC agencies across a number of states have seen enrollment drops that they attribute largely to fears about public charge.6 A survey conducted prior to the final rule found that one in seven adults in immigrant families reported avoiding public benefit programs for fear of risking future green card status, and more than one in five adults in low-income immigrant families reported this fear.7

Characteristics of Noncitizens without LPR status

Using SIPP 2014 Panel data, we show characteristics that DHS could consider in a public charge determination under the rule among noncitizens who originally entered the U.S. without LPR status. Specifically, the analysis examines age, self-reported health status, family income, health insurance type, employment, education, and English proficiency (Appendix B). As noted, officials also will consider previous or current use of public benefits. However, because very few people without a green card are eligible for these programs who would be subject to a public charge test, this analysis does not include estimates of use of public programs.

These estimates illustrate the share of noncitizens living in the U.S. who might face barriers to adjusting to LPR status under the rule based on certain characteristics. Due to data limitations, they do not provide a precise count of the number of people within the U.S. who would be subject to public charge determinations. The estimates do not account for people who DHS could deny entry into the U.S. due to a public charge determination and do not account for all factors that DHS could consider in a public charge determination. As noted, officials would take into account the totality of an individual’s circumstances, and no single factor would govern a determination. How DHS would operationalize its assessment of factors may differ from SIPP’s measurement of characteristics. (See Appendix A: Methods for more detail.)

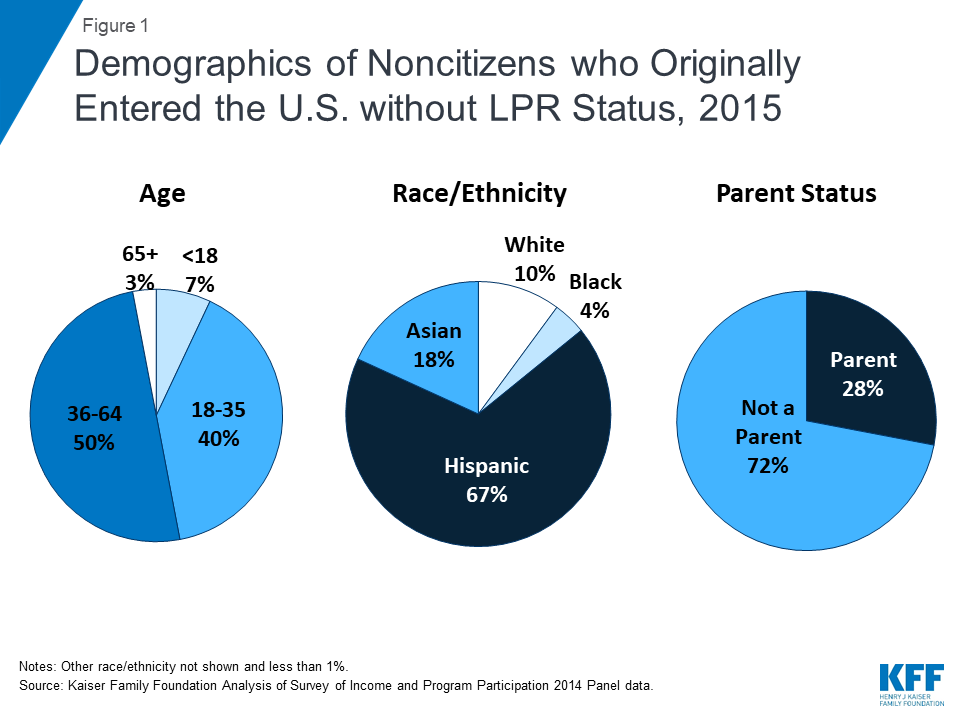

Noncitizens who entered the U.S. without LPR status include individuals across different ages, races/ethnicities, and family statuses. Although many were nonelderly Hispanic adults without a dependent child, 7% are a child, more than one in four is a parent (28%), and one-third (33%) is another race or ethnicity, including nearly one in five (18%) who is Asian (Figure 1).

Nearly eight in ten (79%) noncitizens who entered the U.S. without LPR status have at least one characteristic that DHS could weigh negatively in a public charge determination under the rule. The most common characteristics examined that DHS could consider as negative factors include no private health coverage (56%), no high school diploma (39%), and having income below the new 125% FPL8 standard established by the rule (32%). (Figure 2 and Appendix B).

More than one in four (27%) noncitizens who originally entered the U.S. without LPR status have a characteristic that DHS could consider a heavily weighted negative factor examined in this analysis. Potential heavily weighted negative factors examined in this analysis include not being employed and not a full-time student or primary caregiver (29%), and having a disability that limits the ability to work and lacking private health coverage (3%). The rule identifies other heavily weighted negative factors that were not included in this analysis, including receipt of a public benefit for more than 12 of the previous 36 months and being found previously inadmissible or deportable on public charge grounds. As noted, very few people without a green card are eligible for these programs who would be subject to a public charge test. SIPP data do not provide information on previous determinations of inadmissibility or deportability based on public charge grounds.

Nearly all of noncitizens who originally entered without LPR status have at least one characteristic that DHS could consider as a positive factor. The most common positive factors are no physical or mental health disability (95%), excellent, very good, or good health (90%), and being of working age (between age 18 and 61) (88%). Over half (55%) have a heavily weighted positive factor, which includes having private health insurance (44%) or having family income at or above 250% FPL (36%). Given the high prevalence of at least one positive factor among the population, it’s unclear how officials would weigh the presence of a positive factor in a public charge test. As noted, officials will make public charge determinations based on a totality of an individual’s circumstances. However, the rule does not specify how officials will weigh different factors against each other, leaving officials significant discretion in making determinations on a case-by-case basis.

Nearly seven in ten (68%) of U.S. citizens (U.S. born and naturalized) also had one or more characteristics that DHS could potentially weigh negatively if they were subject to a public charge determination. Citizens were more likely than noncitizens who entered the U.S. without LPR status to have certain characteristics that DHS could consider negative, including being a child or older than age 61 and reporting fair or poor health and having a physical or mental disability that limits their ability to work (Appendix B).

Impact on Medicaid Enrollment

We also illustrate the number of Medicaid and CHIP enrollees who are noncitizens or citizens living in a household with at least one noncitizen who could disenroll under different potential disenrollment scenarios. We use 2017 American Community Survey (ACS) data for this analysis as ACS provides more recent estimates of health coverage than available through SIPP. Although CHIP was not included as a public benefit in the rule, many individuals are not able to distinguish between their enrollment in Medicaid versus CHIP, and ACS data do not provide separate Medicaid and CHIP coverage measures. As noted, previous experience and recent research suggests that the proposed rule may lead to broader disenrollment among individuals in families with immigrants beyond those the rule directly affects.

We applied disenrollment rates of 15%, 25%, and 35% to the total number of Medicaid and CHIP enrollees who are noncitizens or citizens living in a household with at least one noncitizen. It is difficult to predict what actual disenrollment rates may be in response to the rule. These disenrollment rates illustrate a range of potential impacts and draw on previous research on the chilling effect welfare reform had on enrollment in health coverage among immigrant families.9 As noted, a 2019 survey fielded prior to finalization of the rule found that one in seven (13.7%) of adults in immigrant families reported avoiding public benefit programs for fear of risking future green card status, and more than one in five (20.7%) adults in low-income immigrant families reported this fear.10

According to the ACS data, there were over 13.5 million Medicaid/CHIP enrollees who were noncitizens or citizens living in a household with at least one noncitizen, including 7.6 million children, who may be at risk for decreased enrollment as a result of the rule. If the proposed rule leads to disenrollment rates ranging from 15% to 35%, between 2.0 million and 4.7 million Medicaid and CHIP enrollees who are noncitizens or citizens living in a family with at least one noncitizen would disenroll (Figure 3). Because very few noncitizens are eligible for Medicaid would be subject to public charge, this disenrollment would primarily be due to chilling effects of fear and confusion. The estimates provide illustrative examples and, due to data limitations, may reflect both an undercount of noncitizens and an overestimate of noncitizens receiving Medicaid. (See Appendix A: Methods for more detail.)

Beyond potential disenrollment, the proposed rule may also deter new enrollment among the nearly 1.8 million uninsured individuals who are eligible for Medicaid and CHIP but not enrolled and are noncitizens or live in a household with a noncitizen. Specifically, there are 652,200 noncitizen adults and 219,100 noncitizen children who are uninsured but eligible for Medicaid or CHIP. In addition, there are 366,800 uninsured citizen adults and 602,400 uninsured citizen children who are eligible for one of the programs and live in a household with a noncitizen.11 Given continually evolving immigration trends, potential effects of the new rule on lawful immigration in the future, and families’ increased fears of accessing programs, the number of people living in a household with a noncitizen who enroll in Medicaid and CHIP may continually decline over time.

Implications

The rule will make it more difficult for some individuals, particularly those with low incomes and health needs, to obtain LPR status or immigrate to the U.S. For example, a full-time worker in a family of three earning the federal minimum wage would not have sufficient annual income ($15,080) to meet the new income standard established in the rule, which would be $26,663 for a family of three. As such, the rule will affect future immigration opportunities for individuals and families. The rule may also increase barriers to family reunification and potentially lead to family separation, particularly among families with mixed immigration statuses. For example, if DHS denies an individual a green card and that individual loses permission to remain in the U.S due to a public charge determination, he or she may have to leave other family members, such as a spouse or child who is a citizen or who has LPR status, in the U.S.

Reduced participation in Medicaid and other programs would negatively affect the health and financial stability of immigrant families and the growth and healthy development of their children, who are predominantly U.S.-born. Coverage losses would reduce access to care for families, contributing to worse health outcomes. Reduced participation in nutrition and other programs would likely compound these effects. In addition, the losses in coverage would lead to lost revenues and increased uncompensated care for providers and have broader spillover effects within communities.

This brief was prepared by Samantha Artiga and Rachel Garfield, with the Kaiser Family Foundation, and Anthony Damico, an independent consultant to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Appendices

Appendix A: Methods

The findings presented in this brief are based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Wave 3 of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 2014 Panel and 2017 American Community Survey (ACS) data. SIPP enables us to directly measure individuals’ immigration status at the time they entered the U.S. and health status. SIPP also provides measures of health coverage, but 2015 is the most recent year of data available. Because 2015 was a year of substantial transition for Medicaid due to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, we base our Medicaid and CHIP disenrollment analysis on 2017 ACS data.

We classified people as not having LPR status when originally entering the U.S. based on a SIPP question that asks, “What was [respondent’s] immigration status when he/she first moved to the United States?” In addition to measuring people who might adjust to LPR status in the future, who would be subject to a public charge determination (unless they fall into an exempt category), this measure includes noncitizens who have adjusted to LPR status since arriving into the U.S. It also includes nonimmigrants and undocumented immigrants who do not have a current pathway to adjust to LPR status. Our testing of different citizenship measures led to overall similar patterns. The 2014 SIPP shows 17.8 million noncitizens, including 7.4 million of whom originally entered the country without LPR status. Due to underreporting of noncitizens and legal immigration status in the SIPP, these estimates may reflect an undercount of the total noncitizen population and especially the undocumented population. Given this potential undercount—and that the group of noncitizens without LPR status includes some individuals who have since adjusted to LPR status as well as nonimmigrants and undocumented immigrants who do not have a pathway to adjust to LPR status— our analysis of characteristics that DHS could consider negative in public charge determinations focuses on shares rather than absolute numbers of affected individuals.

For the estimates of the share of noncitizens without LPR status living within the U.S. who have characteristics that DHS could weigh negatively in a public charge determination under the proposed rule, we used SIPP to measure age, poverty and work status, insurance status, education, English proficiency, and health status and classified each factor as positive or negative based on the rule’s description of how DHS would consider the characteristic. DHS’ implementation and operationalization of its assessment of factors may differ from SIPP’s measurement of characteristics.

In our analysis of household income, we use 125% of the Census poverty threshold, or $23,848 for a family of three in 2015. Census poverty thresholds are measured slightly differently than HHS poverty guidelines but lead to similar poverty levels for incomes of similar household size. In the rule, DHS provides a specific definition of a household to be used in the calculation of household income. Thus, the final income cutoff for a particular family to meet the 125% of poverty rule as implemented may differ from our measurement or that used by other programs.

We base the Medicaid and CHIP potential disenrollment analysis on 2017 ACS data. These data show that over 13.5 million Medicaid/CHIP enrollees were noncitizens or living in a household with at least one noncitizen. These data on Medicaid enrollees reflect both an undercount of noncitizens in the survey data (as noted above) as well as an overestimate of the share of noncitizens participating in Medicaid as it includes some who may be reporting emergency Medicaid or other state or local health assistance programs as Medicaid coverage.

For estimates of potential changes in coverage due to public charge policies, we present several scenarios using different disenrollment rates for Medicaid and CHIP. These disenrollment rates drew on previous research that showed decreased enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP among immigrant families after welfare reform.12 For example, Kaushal and Kaestner found that after new eligibility restrictions were implemented for recent immigrants as part of welfare reform, there was 25% disenrollment among children of foreign-born parents from Medicaid even though the majority of these children were not affected by the eligibility changes and remained eligible.13 Using this 25% disenrollment rate as a mid-range target, we assume a range of disenrollment rates from a low of 15% to a high of 35%. However, it remains uncertain what share of individuals may disenroll from Medicaid and CHIP in response to the proposed rule. Although the welfare reform experience is instructive of chilling effects among immigrant families broadly, it was associated with changes to program eligibility for immigrants. In contrast, this rule would change the potential consequences of participating in programs on an individual’s immigration status.

Appendix B

| Characteristics that DHS Could Consider in Public Charge Determinations by Citizenship Status, 2015 | |||||

| Potential Positive or Negative Factor? | Heavily Weighted? | Non-LPR Noncitizen | Total Noncitizens | Citizens | |

| Age | |||||

| 17 or younger | Negative | 7% | 8% | 22% | |

| 18 to 61 | Positive | 88% | 84% | 58% | |

| 62 or older | Negative | 6% | 8% | 21% | |

| Health Status | |||||

| No Physical or Mental Health Disability | Positive | 95% | 94% | 86% | |

| Physical or Mental Health Disability | Negative | 5% | 6% | 14% | |

| Excellent, Very Good, or Good Health | Positive | 90% | 90% | 86% | |

| Fair or Poor health | Negative | 10% | 10% | 14% | |

| Physical or Mental Health Disability and No Private Coverage | Negative | Y | 3% | 4% | 7% |

| Family Income | |||||

| Less than 125% Federal Poverty Level (FPL) | Negative | 32% | 28% | 16% | |

| 125% to less than 250% FPL | Positive | 32% | 29% | 22% | |

| 250% FPL or more | Positive | Y | 36% | 43% | 62% |

| Health Coverage | |||||

| Private Coverage | Positive | Y | 44% | 48% | 71% |

| No Private Coverage | Negative | 56% | 52% | 29% | |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed (and age 18+) | Positive | 64% | 62% | 48% | |

| Not employed and not a caregiver (and age 18+) | Negative | 29% | 30% | 30% | |

| Not employed and not a student (and age 18+) | Negative | Y | 27% | 28% | 28% |

| Education | |||||

| Has high school diploma or higher (and age 18+) | Positive | 54% | 56% | 71% | |

| No high school diploma (and age 18+) | Negative | 39% | 36% | 8% | |

| English Proficiency | |||||

| Does Not Have Limited English Proficiency | Positive | 77% | 77% | 99% | |

| Limited English Proficiency | Negative | 23% | 23% | 1% | |

| Any Positive Factor | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Any Heavily Weighted Positive Factor | 55% | 60% | 79% | ||

| Any Negative Factor | 79% | 78% | 68% | ||

| Any Heavily Weighted Negative Factor | 27% | 29% | 29% | ||

| Notes: For each individual subject to a determination, DHS would take into account the totality of his or her circumstances and would retain discretion on how to weigh specific circumstances and factors; no single factor would govern a determination. How DHS would implement and operationalize its assessment of factors under the rule may differ from how SIPP measures characteristics.Source: Kaiser Family Foundation Analysis of Survey of Income and Program Participation 2014 Panel data. | |||||

Endnotes

- Becoming a public charge may also be a basis for deportation in extremely limited circumstances. “Public Charge Fact Sheet,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, https://www.uscis.gov/news/fact-sheets/public-charge-fact-sheet, accessed February 12, 2018. ↩︎

- Services or benefits funded by Medicaid but provided under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and school-based services or benefits provided to individuals who are at or below the oldest age eligible for secondary education as determined under state or local law are not included as a public benefit. ↩︎

- Findings show that recent immigration policy changes have increased fears and confusion among broad groups of immigrants beyond those directly affected by the changes. See Samantha Artiga and Petry Ubri, Living in an Immigrant Family in America: How Fear and Toxic Stress are Affecting Daily Life, Well-Being, & Health, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2017), https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/living-in-an-immigrant-family-in-america-how-fear-and-toxic-stress-are-affecting-daily-life-well-being-health/ and Samantha Artiga and Barbara Lyons, Family Consequences of Detention/Deportation: Effects on Finances, Health, and Well-Being, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2018), https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/family-consequences-of-detention-deportation-effects-on-finances-health-and-well-being/. Similarly, earlier experiences show that welfare reform changes increased confusion and fear about enrolling in public benefits among immigrant families beyond those directly affected by the changes. See. Neeraj Kaushal and Robert Kaestner, “Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants,” Health Services Research,40(3), (June 2005), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361164/; Michael Fix and Jeffrey Passel, Trends in Noncitizens’ and Citizens’ Use of Public Benefits Following Welfare Reform 1994-97 (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, March 1, 1999) https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/69781/408086-Trends-in-Noncitizens-and-Citizens-Use-of-Public-Benefits-Following-Welfare-Reform.pdf; Namratha R. Kandula, et. al, “The Unintended Impact of Welfare Reform on the Medicaid Enrollment of Eligible Immigrants, Health Services Research, 39(5), (October 2004), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361081/; Rachel Benson Gold, Immigrants and Medicaid After Welfare Reform, (Washington, DC: The Guttmacher Institute, May 1, 2003), https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/05/immigrants-and-medicaid-after-welfare-reform. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga and Petry Ubri, Living in an Immigrant Family in America: How Fear and Toxic Stress are Affecting Daily Life, Well-Being, & Health, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2017), https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/living-in-an-immigrant-family-in-america-how-fear-and-toxic-stress-are-affecting-daily-life-well-being-health/; Samantha Artiga and Barbara Lyons, Family Consequences of Detention/Deportation: Effects on Finances, Health, and Well-Being (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2018),https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/family-consequences-of-detention-deportation-effects-on-finances-health-and-well-being/; and Hamutal Bernstein, Dulce Gonzalez, Michael Karpman, and Stephen Zuckerman, With Public Charge Rule Looming, One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018, (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, May 2019), https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/public-charge-rule-looming-one-seven-adults-immigrant-families-reported-avoiding-public-benefit-programs-2018 ↩︎

- The Children’s Partnership, “California Children in Immigrant Families: The Health Provider Perspective,” 2018, https://www.childrenspartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Provider-Survey-Inforgraphic-.pdf. ↩︎

- Bottemiller Evich, H., “Immigrants, fearing Trump crackdown, drop out of nutrition programs,” Politico (Washington, DC, September 4, 2018). Accessed July 18, 2019, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/09/03/immigrants-nutrition-food-trump-crackdown-806292 ↩︎

- Hamutal Bernstein, Dulce Gonzalez, Michael Karpman, and Stephen Zuckerman, With Public Charge Rule Looming, One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018, (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, May 2019), https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/public-charge-rule-looming-one-seven-adults-immigrant-families-reported-avoiding-public-benefit-programs-2018 ↩︎

- In our data analysis, we use the Census poverty threshold, which was $23,848 for a family of three in 2015. Census poverty thresholds are measured slightly differently than HHS poverty guidelines but lead to similar poverty levels for incomes of similar household size. See Methods for more detail. ↩︎

- Earlier experiences show that welfare reform changes increased confusion and fear about enrolling in public benefits among immigrant families beyond those directly affected by the changes. See. Neeraj Kaushal and Robert Kaestner, “Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants,” Health Services Research,40(3), (June 2005), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361164/; Michael Fix and Jeffrey Passel, Trends in Noncitizens’ and Citizens’ Use of Public Benefits Following Welfare Reform 1994-97 (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, March 1, 1999) https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/69781/408086-Trends-in-Noncitizens-and-Citizens-Use-of-Public-Benefits-Following-Welfare-Reform.pdf; Namratha R. Kandula, et. al, “The Unintended Impact of Welfare Reform on the Medicaid Enrollment of Eligible Immigrants, Health Services Research, 39(5), (October 2004), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361081/; Rachel Benson Gold, Immigrants and Medicaid After Welfare Reform, (Washington, DC: The Guttmacher Institute, May 1, 2003), https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/05/immigrants-and-medicaid-after-welfare-reform. ↩︎

- Hamutal Bernstein, Dulce Gonzalez, Michael Karpman, and Stephen Zuckerman, With Public Charge Rule Looming, One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018, (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, May 2019), https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/public-charge-rule-looming-one-seven-adults-immigrant-families-reported-avoiding-public-benefit-programs-2018 ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2017 American Community Survey data. ↩︎

- Neeraj Kaushal and Robert Kaestner, “Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants,” Health Services Research,40(3), (June 2005), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361164/; Michael Fix and Jeffrey Passel, Trends in Noncitizens’ and Citizens’ Use of Public Benefits Following Welfare Reform 1994-97 (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, March 1, 1999) https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/69781/408086-Trends-in-Noncitizens-and-Citizens-Use-of-Public-Benefits-Following-Welfare-Reform.pdf; Namratha R. Kandula, et. al, “The Unintended Impact of Welfare Reform on the Medicaid Enrollment of Eligible Immigrants, Health Services Research, 39(5), (October 2004), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361081/; Rachel Benson Gold, Immigrants and Medicaid After Welfare Reform, (Washington, DC: The Guttmacher Institute, May 1, 2003), https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/05/immigrants-and-medicaid-after-welfare-reform. ↩︎

- Neeraj Kaushal and Robert Kaestner, “Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants,” Health Services Research,40(3), (June 2005), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361164/ ↩︎