Modern Era Medicaid: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 2015

Tricia Brooks, Joe Touschner, Samantha Artiga, Jessica Stephens, and Alexandra Gates

Published:

Executive Summary

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has contributed to a significant transformation of Medicaid, broadening it as the base of coverage for the low-income population and accelerating state efforts to move from antiquated, paper-driven enrollment processes to a new modernized enrollment experience for individuals. January 1, 2015 marks the first anniversary of key ACA Medicaid provisions, including the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults and new rules for streamlined enrollment and renewal processes that coordinate across insurance affordability programs, including Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the Health Insurance Marketplaces. Throughout 2014, states continued to develop their data-driven systems and re-engineer their business practices to fulfill the ACA’s vision. This 13th annual 50-state survey of Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost-sharing policies as of January 2015 provides a snapshot of state Medicaid and CHIP policies in place one year into the post-ACA era.

Eligibility for Adults, Children, and Pregnant Women

As of January 1, 2015, 28 states set their Medicaid income eligibility levels for parents and other adults to at least 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), reflecting their implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion. This count includes New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, which made decisions during 2014 to expand. Among these states, median income eligibility levels for adults have increased compared to pre-ACA levels, particularly for childless adults who were historically excluded from the Medicaid program (ES-Figure 1). There is no deadline for states to expand Medicaid, and additional states may decide to expand in the coming year.

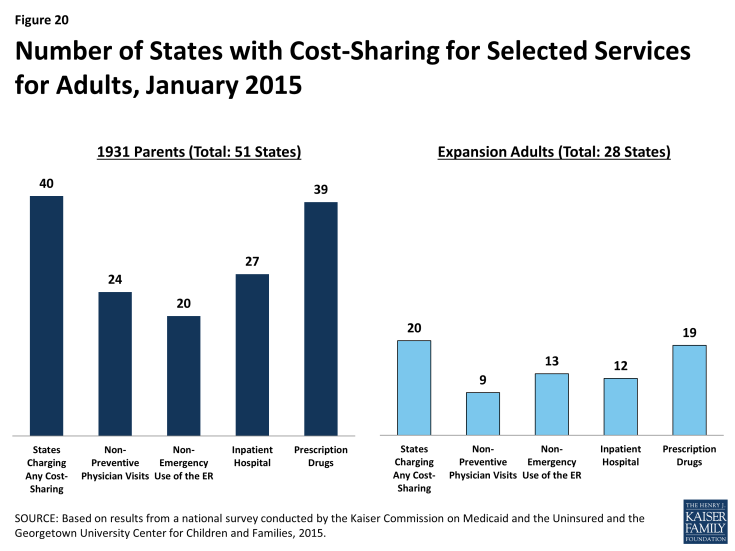

Figure ES-1: Median Medicaid Income Eligibility Levels for Adults as a Percent of the FPL in States that Adopted the Medicaid Expansion, January 2013 and January 2015

Eligibility levels remain very limited for adults in the 23 states not adopting the Medicaid expansion at this time. In all but one of these states (Wisconsin), childless adults remain ineligible for Medicaid regardless of their incomes, while Medicaid eligibility levels for parents are below poverty in 19 states (ES-Figure 2).1 In these states, many poor adults earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for tax subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage, which are not available to those with incomes below 100 percent of the FPL. Other Kaiser Family Foundation analysis finds that nearly four million poor uninsured adults fall into a coverage gap as a result of these limited eligibility levels.2

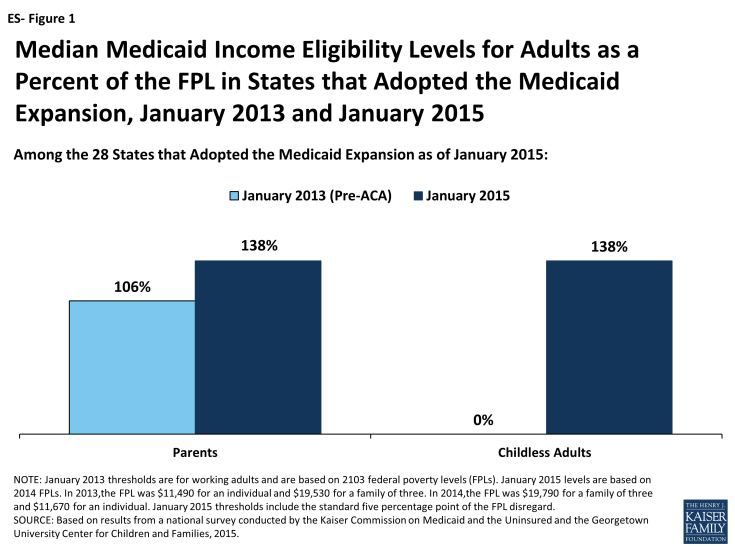

Figure ES-2: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults in States Not Adopting the Medicaid Expansion at this Time, January 2015

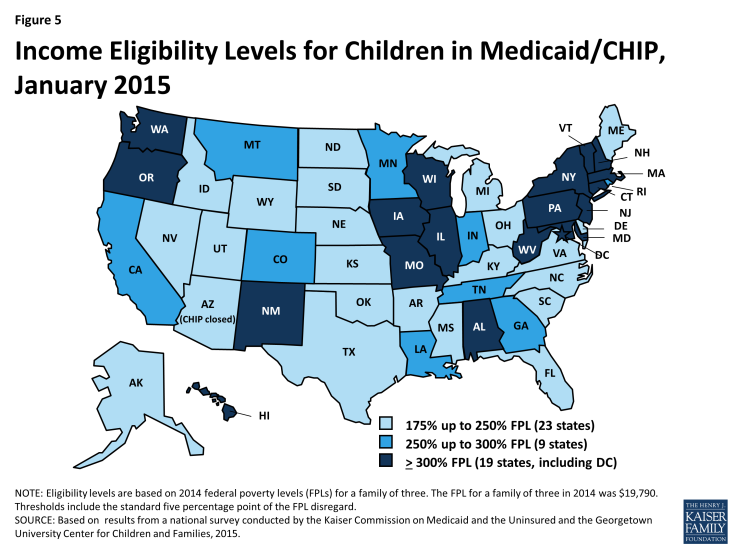

Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children and pregnant women remains strong. As of January 1, 2015, all but two states cover children at or above 200 percent of the FPL through Medicaid and CHIP with 19 states covering children at or above 300 percent of the FPL. A total of 33 states cover pregnant women at or above 200 percent of the FPL. Building on many years of progress, states also continued to take up options that expand children’s access to coverage. Consistent with the ACA’s vision of a seamless continuum of coverage options, 21 states eliminated waiting periods in CHIP, including California which transitioned its separate CHIP program into Medicaid. Illinois expanded CHIP coverage in 2013 to 317% FPL, with children above 209% FPL subject to a 3-month waiting period. Reflecting this state action, as of January 1, 2015, 33 states have no period of time that a child must be without group coverage prior to enrolling. In addition, 28 states have now eliminated the five-year waiting period for lawfully residing immigrant children, while 23 have done so for pregnant women, reflecting the recent adoption of this option in several states. Coverage for children remains protected through 2019 under ACA provisions that prohibit states from applying any restrictions in eligibility or enrollment for children.

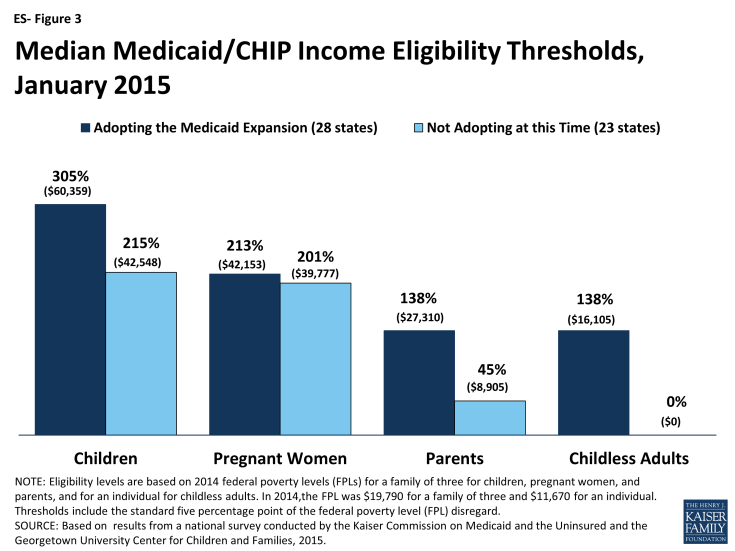

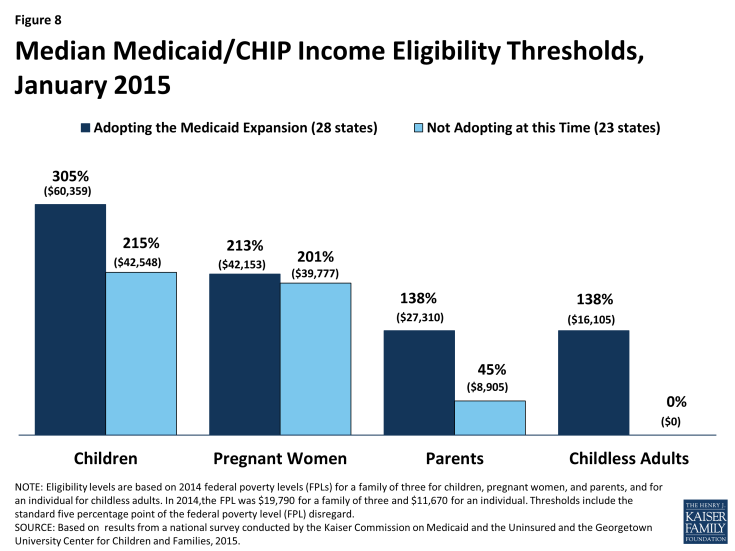

Although eligibility levels for adults markedly increased over pre-ACA standards as a result of the Medicaid expansion, they remain well below those of children and pregnant women. Among states that expanded Medicaid, the median eligibility level for both parents and other adults is 138 percent of the FPL. However, among the 23 states that have not expanded, the median eligibility level is just 45 percent of the FPL for parents and 0 percent of the FPL for childless adults. Comparatively, the median limits for children and pregnant women are significantly higher in both expansion and non-expansion states (ES-Figure 3).

Progress Toward Streamlined Enrollment and Renewal Processes

States have achieved major progress implementing the modernized and streamlined enrollment and renewal processes under the ACA, but work continues in many areas. Reflecting this ongoing effort, the functionality of eligibility and enrollment systems is rapidly changing and improving on a week-to-week basis. Thus, what is reported here is a snapshot of processes and system capabilities as of January 2015.

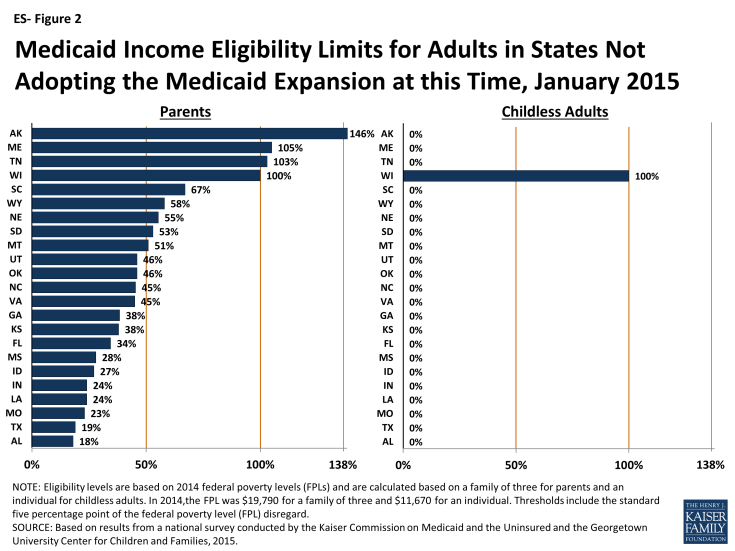

As of January 1, 2015, individuals can apply online for Medicaid at the state level in all but one state, and the majority of states are accepting Medicaid applications by phone (ES-Figure 4). Under the ACA, states must provide individuals the option to apply online for Medicaid at the state level, which currently is available in all states, except Tennessee, where individuals can only apply online through the Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM). Most states (36) also provide individuals the opportunity to create an online account for management of their Medicaid coverage. States continue to build features into these accounts, such as the ability to report changes, view notices, and upload documents. States also are required to provide individuals the option to apply by phone. Most states (47) accept telephone applications for Medicaid through the Medicaid agency and/or the State-based Marketplace (SBM), while the remaining states are delayed in providing this option.

Figure ES-4: Number of States with Online and Telephone Applications and Online Accounts in Medicaid, January 2015

States have established eligibility verification policies that seek to rely on electronic data and minimize paperwork for individuals. As required by the ACA, all states seek to rely on electronic data sources to verify incomes of Medicaid and CHIP applicants, with 40 states verifying income prior to enrollment and 11 verifying after enrollment. Some states are relying solely on the federal data services hub, which consolidates data from the Internal Revenue Services, the Social Security Administration, the Department of Homeland Security, and a commercial wage database, while others are tapping state data sources in addition to or in lieu of the federal data hub. For cases in which there are differences between self-reported income and data from electronic sources, two-thirds of states (33) have elected to provide a broader standard than required to consider the data to be “reasonably compatible” and accept the self-reported income. Further, most states have taken up options to minimize paperwork burdens for applicants and states by relying on self-attestation of at least some non-financial eligibility criteria, such as age, state residency, and/or household size.

Work continues to implement streamlined renewal processes. Similar to enrollment processes, the ACA also calls for highly automated, paperless renewal procedures for Medicaid and CHIP. To ease the transition to new renewal processes, CMS offered states an option to temporarily delay renewals, which 34 states took up in Medicaid and 22 states took up in CHIP during 2014. Most states have completed all renewals that were originally due in 2014, although 17 states are extending some of these renewals into 2015. However, many states are continuing work to transition to new streamlined renewal procedures and face a range of challenges, including developing system capacity, transferring data for existing enrollees from old mainframe-based systems to their new modern technology platforms, and generating notices for individuals. In the interim, a number of states are relying on mitigation strategies such as mailing forms to individuals to request the information needed to complete renewal.

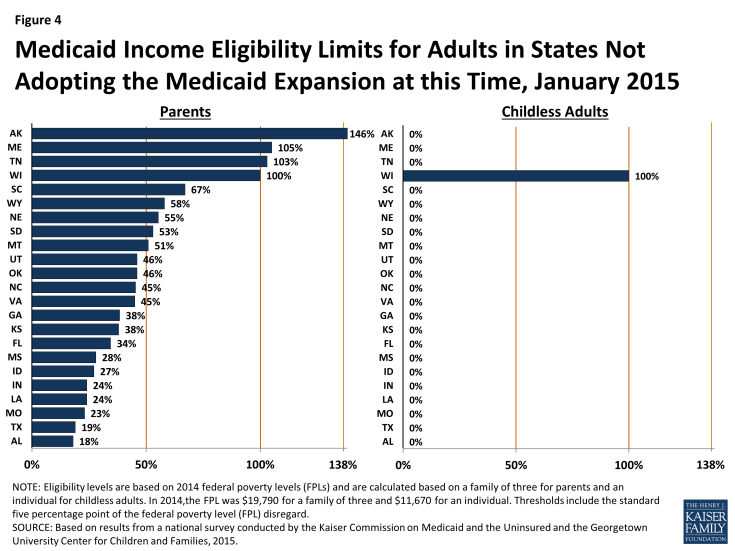

A range of additional options facilitates enrollment and renewal of eligible individuals in some states. The ACA establishes new authority for hospitals to provide temporary access to Medicaid coverage by conducting presumptive eligibility determinations while a full application is in process, which states are in varying stages of implementing. In addition, longstanding policy allows states to authorize qualified entities, such as hospitals, community health centers, and schools, to make presumptive eligibility determinations for children and pregnant women, which the ACA expanded to include parents and other adults. As of January 2015, 28 states authorize entities to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations for children, pregnant women, parents, or other adults (ES-Figure 5). Moreover, since Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) was established in 2009, states have had the option to use findings from other means-tested programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to determine children eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, which ten states currently utilize. In 2013, CMS offered states additional facilitated enrollment options, including using SNAP data to identify and enroll eligible individuals and using child enrollment data to expedite parent enrollment. Eight states have taken up one or both of these strategies, which have contributed to success enrolling newly eligible adults and children and reduced administrative costs.3 In addition, to support stable coverage over time, nine states utilize ELE at renewal and 31 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid or CHIP.

Figure ES-5: Number of States Adopting Targeted Strategies to Streamline Enrollment and Renewal of Eligible Individuals, January 2015

States’ choices with regard to the integration of their Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility determination systems affect coordination across coverage programs. All states must maintain a Medicaid eligibility determination system, but states with an SBM may operate a single, integrated system that determines eligibility for both Medicaid and Marketplace coverage, which 12 states do. The remaining states have separate eligibility determination systems for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. In states with separate systems (including all 37 states relying on the FFM for eligibility and enrollment functions and 2 SBM states with separate state-level Medicaid and Marketplace systems), electronic data, known as account transfers, must be exchanged between the systems to provide a seamless enrollment experience for individuals. During 2014, difficulties with this coordination contributed to delays in Medicaid enrollment. The federal government and states have sought to address these issues, but the extra steps needed to determine eligibility, along with the higher volume of applications during open enrollment, may still result in backlogs in some states.4

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

In general, premiums and cost-sharing remain limited in Medicaid and CHIP. As of January 2015, 30 states charge premiums or enrollment fees for children, primarily in CHIP, and 26 states have cost-sharing for children. No states charge premiums for parents or ACA expansion adults in traditional Medicaid, reflecting the fact that eligibility limits for adults in most states are below the level at which they can be charged under federal rules. However, four states (AR, IA, MI, and PA) have received waiver approval to charge monthly payments not otherwise allowed under federal rules for some adults. Most states charge nominal cost-sharing for low-income parents and expansion adults.

Looking Ahead

One year after the launch of the major Medicaid provisions of the ACA, there have been significant gains in coverage opportunities for low-income adults, most notably with increased eligibility levels for parents and childless adults in states that have expanded Medicaid. There is no deadline for states to expand Medicaid, and debate over the adult expansion will continue in some states in 2015. Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children and pregnant women remains strong across states, but without Congressional action there will not be continued funding for CHIP beyond September 2015. If CHIP funding expires, some children may lose coverage and some may face higher premiums and cost-sharing for coverage.5 The loss of enhanced CHIP funding would also have budgetary implications for states. On the operational and systems side, many states have achieved significant progress toward realizing the ACA’s vision of a modernized, streamlined enrollment system, but work continues in many areas, including establishing automated renewal processes as well as enhancing and expanding the functionalities of their systems.

Introduction

At the one-year anniversary of implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) coverage provisions, states continue work to transform Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to realize the ACA’s goals of expanded coverage and a streamlined enrollment system. While many states have worked to enhance access to coverage and simplify Medicaid and CHIP enrollment and renewal processes for a number of years, particularly for children, the ACA has served as a key impetus to accelerate these efforts and move the Medicaid program into a new era to serve as a broad base of coverage for the low-income population and provide a modernized enrollment experience for individuals.

Pivotal action took place in 2014, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and states working together to implement the ACA’s new eligibility, enrollment, and renewal rules. More than half of the states moved forward with the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, and states made significant headway in adopting the law’s streamlined enrollment and renewal processes. However, implementation remains a work in progress with some states further ahead than others. Looking ahead, many states are now focused on enhancing and improving system functionalities, smoothing out transitions between Medicaid and Marketplace coverage, and progressing to highly-automated renewal procedures.

This report annually surveys Medicaid and CHIP program officials to track eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and premium and cost-sharing policies. Given the fast-paced policy environment leading up to January 1, 2014, when key ACA coverage provisions went into effect, an abbreviated report based on publicly available data was released in November 2013. For this 13th annual report, we return to conducting interviews with state Medicaid and CHIP officials to gather information on key policies that are in effect as of January 1, 2015.

The report includes information on Medicaid policies for children, pregnant women, parents, and the new adult expansion group, as well as coverage for children and pregnant women under CHIP.1 Given that state eligibility and enrollment systems and ACA implementation efforts are rapidly evolving, this report provides a point-in-time view, a snapshot. Importantly, it provides a key measure of state Medicaid and CHIP policies in a new era under the ACA. The report is organized into four sections: Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment and Renewal Processes, Eligibility Determination Systems, and Premiums and Cost-Sharing. State-specific information is available in Tables 1 to 19 at the end of the report.

Report

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

As enacted, the ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($27,310 for a family of three in 2014), although this core provision was effectively made a state option by the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling on the ACA. However, other eligibility changes in the law were unaffected by the Court’s decision, including establishing a new minimum coverage level of 138 percent of the FPL for children of all ages in Medicaid, helping to align Medicaid coverage across children. The ACA also changed the method for determining financial eligibility for Medicaid for children, pregnant women, parents, and adults and CHIP to a standard based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI).1 This new approach is intended to prevent gaps in coverage between programs by largely adopting the rules for determining eligibility for subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage. While these changes went into effect on January 1, 2014, some states continued to refine the conversion of their pre-ACA eligibility levels to MAGI-based standards. The findings below reflect eligibility levels for parents and other non-disabled adults, children, and pregnant women in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 1, 2015. They highlight Medicaid’s expanded role for low-income adults under the ACA and its continued role as a primary source of coverage for children and pregnant women.

Parents and Adults

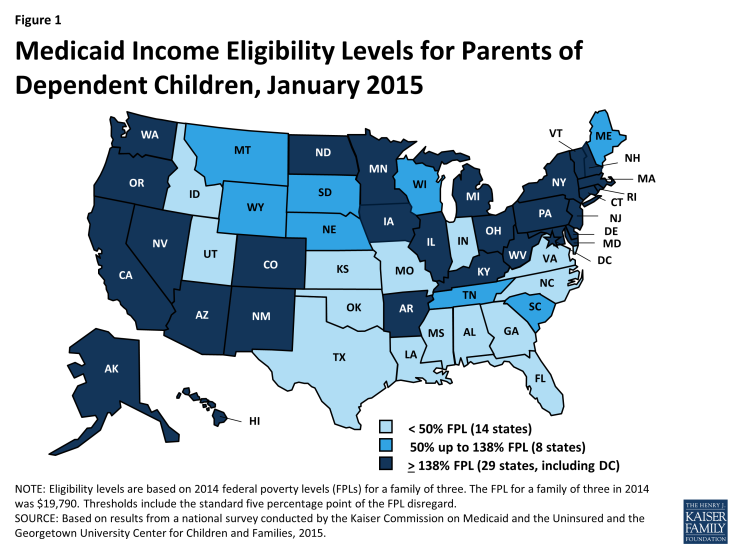

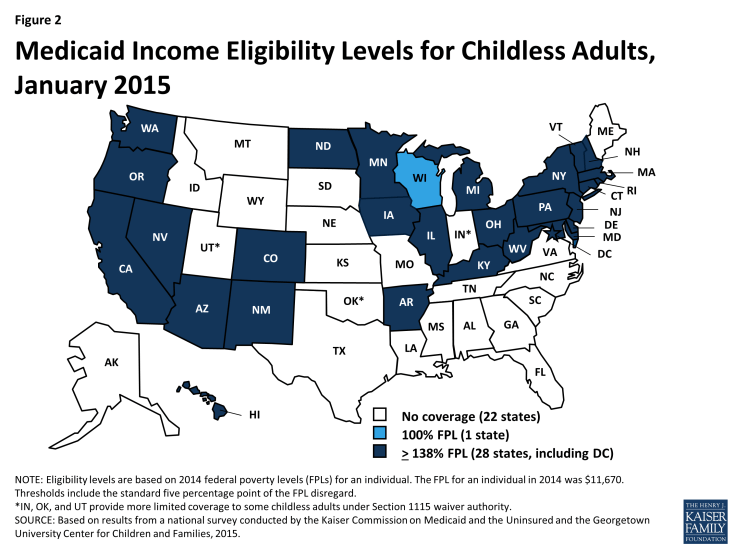

As of January 1, 2015, 28 states set their Medicaid income eligibility levels for parents and other adults to at least 138 percent of the FPL, reflecting their implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion (Figures 1 and 2). This count includes New Hampshire and Pennsylvania, which made decisions during 2014 to expand. Most states adopted the expansion consistent with federal rules and options provided under the ACA, but four states (AR, IA, MI, and PA) obtained Section 1115 waivers to expand Medicaid in ways that extend beyond the flexibility provided by the law.2 There is no deadline for states to expand Medicaid and additional states may decide to expand in the coming year. Two expansion states extend Medicaid income eligibility for adults to higher levels. Specifically, in the District of Columbia, parents with incomes up to 221 percent of the FPL and other adults with incomes up to 215 percent of the FPL are eligible, and Connecticut covers parents with incomes up to 201 percent of the FPL. Minnesota became the first state to implement a Basic Health Program (BHP) established by the ACA and transferred coverage for Medicaid enrollees with incomes between 138 and 200 percent of the FPL to the BHP as of January 1, 2015.

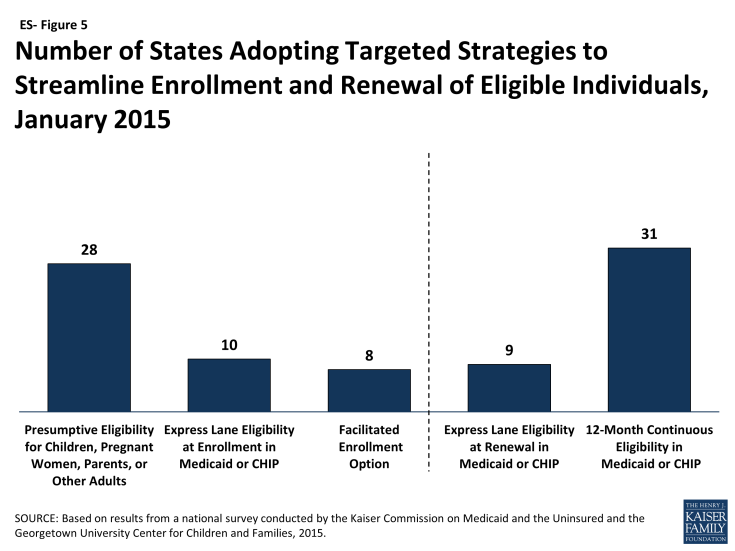

Among states that have implemented the Medicaid expansion, there have been increases in income eligibility levels for adults compared to pre-ACA levels. In these states, the median income eligibility level for parents rose from 106 percent of the FPL to 138 percent of the FPL. Increases in income eligibility levels for childless adults were even more significant, rising from a median of 0 to 138 percent of the FPL, reflecting the historic exclusion of childless adults from Medicaid prior to the ACA (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Median Medicaid Income Eligibility Levels for Adults as a Percent of the FPL in States that Adopted the Medicaid Expansion, January 2013 and January 2015

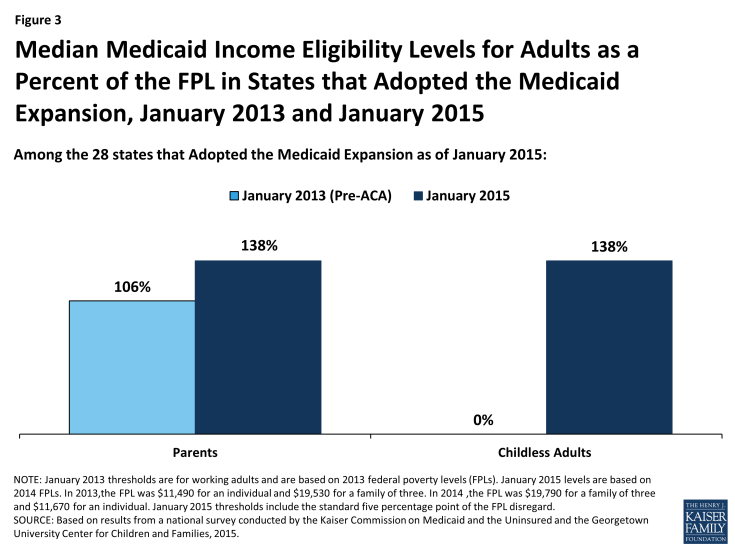

Medicaid income eligibility levels for parents remain very low, and, with only one exception, childless adults are ineligible for Medicaid in the 23 states that are not adopting the Medicaid expansion at this time. Fourteen states limit parent eligibility levels to less than half of the poverty level, and only four of the non-expansion states set their income eligibility levels for parents at or above 100 percent of the FPL, including Maine and Wisconsin, which both reduced eligibility levels for parents from pre-ACA levels (Figure 4). Wisconsin is also the only non-expansion state providing full Medicaid coverage to any childless adults, although eligibility at 100 percent of the FPL remains below the expansion level.3 In the other non-expansion states, where Medicaid income eligibility limits for adults are below poverty, many adults earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for tax subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage, which are not available to those with incomes below 100 percent of the FPL. Other Kaiser Family Foundation analysis finds that nearly four million poor uninsured adults fall into a coverage gap as a result of these limited eligibility levels.4 While this study reports FPL equivalents, it also is important to note that 17 non-expansion states base eligibility for parents on dollar thresholds. Most of these states do not routinely update these dollar-based standards, resulting in eligibility levels that erode over time relative to the cost of living.

Figure 4: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults in States Not Adopting the Medicaid Expansion at this Time, January 2015

Children and Pregnant Women

Coverage for children in Medicaid and CHIP remains strong and steady with the median income eligibility limit at 255 percent of the FPL. As of January 1, 2015, 28 states cover children with family incomes at or above 250 percent of the FPL, with 19 extending coverage to 300 percent of the FPL or higher (Figure 5). Only two states (ID, ND) limit children’s eligibility to below 200 percent of the FPL. Underlying these upper limits, eligibility levels reflect the ACA’s new minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138 percent of the FPL for children of all ages. This change resulted in the shift of older children (ages 6 up to 19) with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the FPL from CHIP to Medicaid in 18 of the 36 states maintaining separate CHIP programs, while California, New Hampshire, and Vermont have transitioned all of the children from their separate CHIP programs to Medicaid. States still receive enhanced federal CHIP matching funds for children transferred from CHIP to Medicaid under this requirement. Enrollment remains open for children in all states with separate CHIP programs, except for Arizona, which froze enrollment in its separate CHIP program prior to the ACA. The ACA established protections that prohibit states from applying any restrictions in eligibility or enrollment for children through September 2019.

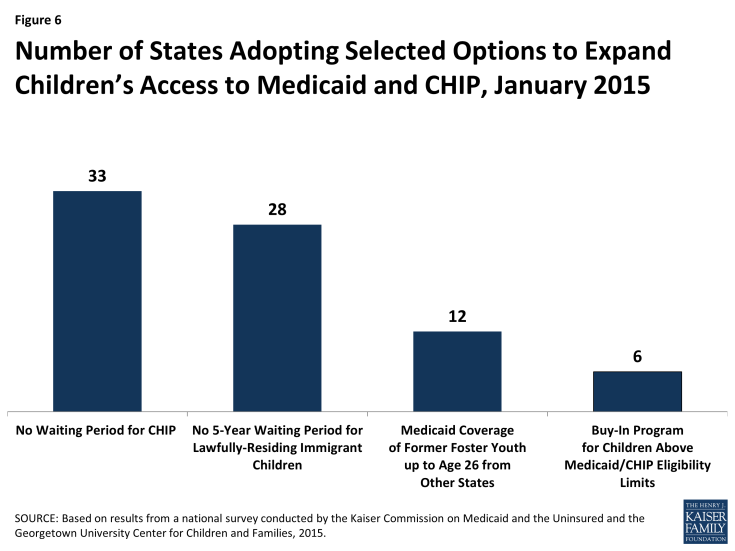

States have continued to take up options that expand children’s access to coverage. Consistent with the ACA’s vision of a seamless continuum of coverage options, 21 states eliminated waiting periods in CHIP, including California which transitioned its separate CHIP program into Medicaid, and seven states reduced their waiting periods to 90 days or less, consistent with new federal rules. Illinois expanded CHIP coverage in 2013, with the expansion group between 209% and 317% FPL subject to a three-month waiting period. Reflecting this state action, as of January 1, 2015, 33 states do not have a waiting period that requires that a child be without group coverage for a specified period of time before enrolling in CHIP (Figure 6). In addition, more than half of all states (28) have taken up the option, established in 2009, to eliminate the five-year waiting period for lawfully-residing immigrant children, with Kentucky, Ohio and, West Virginia recently adopting the option. Additionally, seven states provide fully state- or locally-funded coverage to some children regardless of their immigration status. Under the ACA, all states must provide Medicaid coverage to former foster youth up to age 26 if they were in foster care in the state and enrolled in Medicaid on their 18th birthday. Nearly a quarter of states (12) have chosen to extend this coverage to former foster youth from other states. Six states have maintained programs that allow families with incomes over the upper limit for children’s coverage to buy into Medicaid or CHIP for their children, although this number has declined from its peak of 15 in 2011, reflecting the fact that higher income families now have new coverage options through the Marketplaces.

Figure 6: Number of States Adopting Selected Options to Expand Children’s Access to Medicaid and CHIP, January 2015

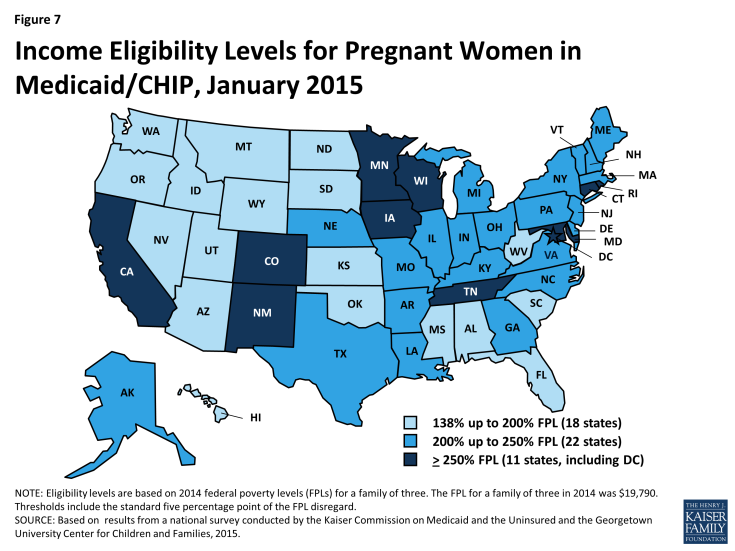

Nearly two-thirds of states (33) cover pregnant women with incomes at or above 200 percent of the FPL (Figure 7). This count reflects the reinstatement of CHIP coverage for pregnant women with incomes up to 205 percent of the FPL in Virginia during 2014. Ohio, West Virginia, and Wyoming also recently took up the option to eliminate the five-year waiting period for lawfully residing immigrant pregnant women, increasing the total number of states that have adopted this option since it was established in 2009 to 23. Further, 15 states cover income-eligible pregnant women regardless of immigration status through CHIP’s unborn child option, while four states provide fully state-funded coverage to some immigrant pregnant women.

Even with the Medicaid expansion, income eligibility levels for parents and other adults remain lower than those for children and pregnant women. The differences between parents and other adults and children and pregnant women are even starker among states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion. In the non-expansion states, the median Medicaid income eligibility level is 45 percent of the FPL for parents and 0 percent of the FPL for other adults, compared to 138 percent of the FPL for parents and adults in expansion states and the significantly higher median Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children and pregnant women in both expansion and non-expansion states (Figure 8).

Enrollment and Renewal Processes

The ACA enacted sweeping changes to transform application, enrollment, and renewal processes in Medicaid and CHIP and coordinate with the new Marketplaces. Together these processes are intended to achieve the ACA’s vision to provide “no wrong door” access to all health coverage options, minimize the paperwork burden on consumers and state agencies, and enhance the consumer experience. Specifically, under the ACA, states must provide multiple options for individuals to apply for health coverage, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person, using a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. In addition, states must seek to rely on electronic data to verify eligibility criteria and renew coverage based on electronic data matches. Adoption of these procedures represents major modernization in many states that previously had relied on antiquated, paper-based enrollment processes for Medicaid and CHIP. States have achieved significant progress adopting many of these processes, but work continues in many areas.

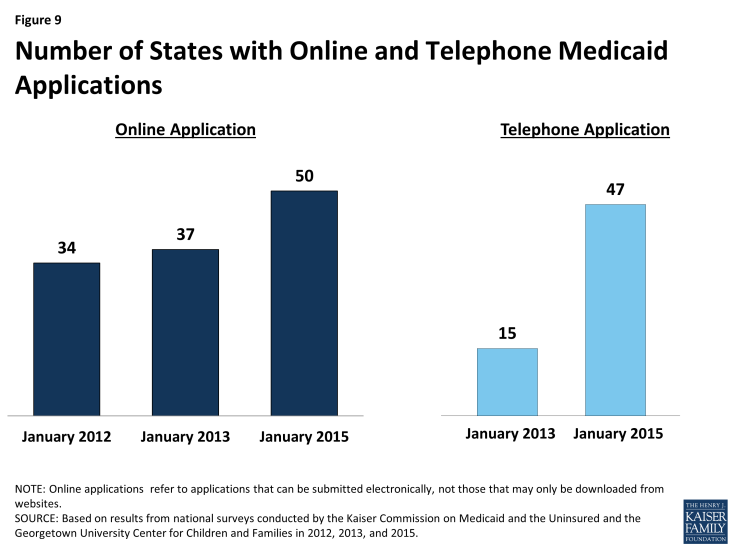

Applications

As of January 1, 2015, individuals can apply online for Medicaid at the state level in all states, except Tennessee. Most states with a State-based Marketplace (SBM) (12 of 17) provide a single integrated online application portal for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. All states relying on the Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM) for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions maintain their own online Medicaid application separate from Healthcare.gov, as required, except Tennessee, where individuals can only apply online for Medicaid through Healthcare.gov. In about half of all states (25), an online multi-benefit application is available that allows individuals to apply simultaneously for Medicaid and other benefits, such as SNAP or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). The availability of an online Medicaid application in nearly all states represents substantial progress from just several years ago; an online option was available in only two-thirds of states (34) as of January 2012 and 37 states as of January 2013 (Figure 9).

The majority of states are accepting Medicaid applications by phone as of January 1, 2015. Medicaid applications can be submitted by telephone at the state level in most states (47) either through the Medicaid agency or the SBM call center, but work continues in the remaining states to support phone-based applications. The broad availability of a telephone application across states also represents marked progress among states in modernizing enrollment processes as only 15 provided this option as of January 2013.

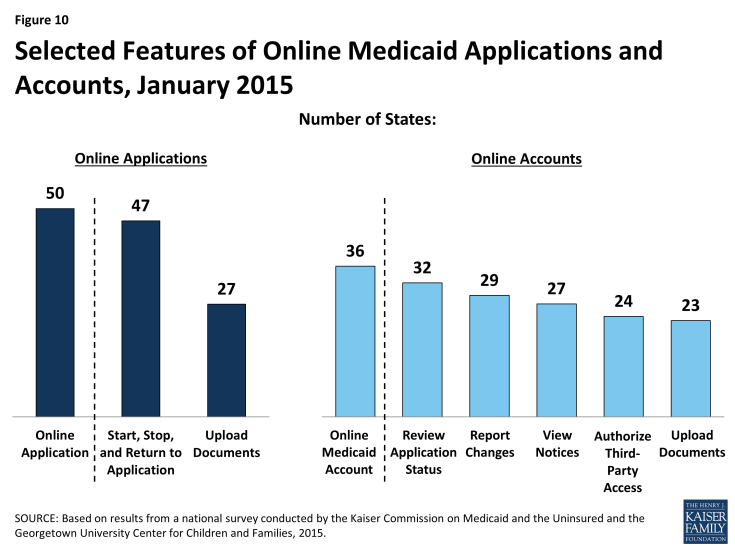

There is variation across states in the functions of online applications and the availability and features of online Medicaid accounts. In most states (47), applicants can start, stop, and return to the online application, and, in just over half of states (27), the online application provides applicants the ability to upload electronic copies of documentation if it is required (Figure 10). More than two-thirds of states (36) also provide individuals the opportunity to create an online account for ongoing management of their Medicaid coverage, which may include the ability to review the status of their application (32 states), report changes (29 states), view notices (27 states), authorize third-party access (24 states), and upload documentation (23 states). Many of these states plan to add capabilities over time and additional states plan to add online accounts in 2015 or beyond.

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

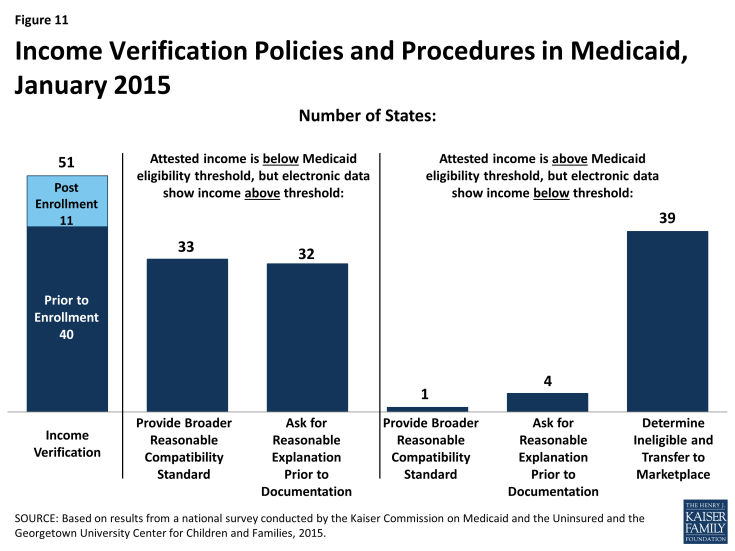

All states are developing their capacities to tap electronic data sources to verify incomes of Medicaid and CHIP applicants, as required by the ACA. States must verify income using electronic data sources to the extent possible. Forty states confirm applicants’ income prior to enrollment, while 11 states process eligibility based on an applicant’s attestation and verify after enrollment (Figure 11). To facilitate electronic verification, a federal data hub was established that allows states to access information from multiple federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration, and the Department of Homeland Security. In addition, states can access other databases that collect state wage information, unemployment compensation, vital statistics, and eligibility for other public programs. Verifying eligibility elements is not only technically complicated, but also requires the establishment of data sharing agreements between agencies that protect the privacy and security of personally identifiable information. These challenges can slow state progress in accessing electronic data sources on a timely basis to verify eligibility. Looking ahead, states are continuing to enhance their data matching capabilities.

Over half of states have opted to set a broader “reasonable compatibility standard” than required to address cases in which there are differences between self-reported income and data from electronic sources. Federal rules require states to disregard differences between self-reported income and an electronic data source if the difference does not affect eligibility (i.e., both are at, above, or below the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility threshold). Thirty-three states have taken up an option to establish a broader reasonable compatibility standard for cases in which self-attested income is below but electronic data sources show income above the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility limit. If the difference is within this reasonable compatibility standard, which is most often 10 percent, the self-reported income is accepted. Regardless of whether they have set a broader reasonable compatibility standard, if data are not reasonably compatible, states may accept a reasonable explanation of the difference (e.g., the individual lost a job) before requiring paper documentation, which 32 states do. Only one state (New Jersey) provides a broader reasonable compatibility standard for cases in which self-reported income is above the Medicaid or CHIP income threshold and electronic data sources show income below the threshold. In these circumstances, most states (39) determine the individual ineligible for Medicaid or CHIP and transfer the account to the Marketplace for determination of eligibility for subsidies.

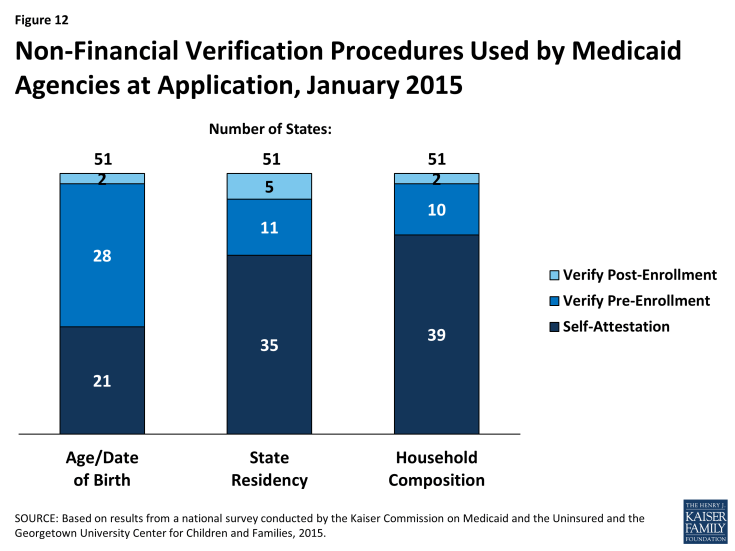

Many states minimize burdens for applicants and states by relying on self-attestation of non-financial eligibility criteria. As is the case with income, states must verify citizenship and immigration status for new applicants through electronic data sources. However, states have additional options to verify other non-financial eligibility criteria, including age/date of birth, state residency, and household composition. For these criteria, states can either verify pre- or post-enrollment or accept self-attestation. Many states accept self–attestation of age/date of birth (21), state residency (35), or household size (39), although verification is required if a state has any conflicting information on file (Figure 12). The remaining states confirm these eligibility criteria prior to enrollment or post enrollment, although most do not verify the information at renewal. Accepting self-attestation simplifies the enrollment process for states and applicants, and past experience shows that reducing paperwork burdens boosts enrollment and retention.1 Historically, some states have been reluctant to minimize documentation requirements due to concerns about penalties associated with inaccurate eligibility determinations. However, moving forward, audits of state eligibility determinations will focus on validating that states’ systems and processes are consistent with the verification plans they must submit to CMS that outline their policies for determining eligibility.

Figure 12: Non-Financial Verification Procedures Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application, January 2015

Facilitated Enrollment Options

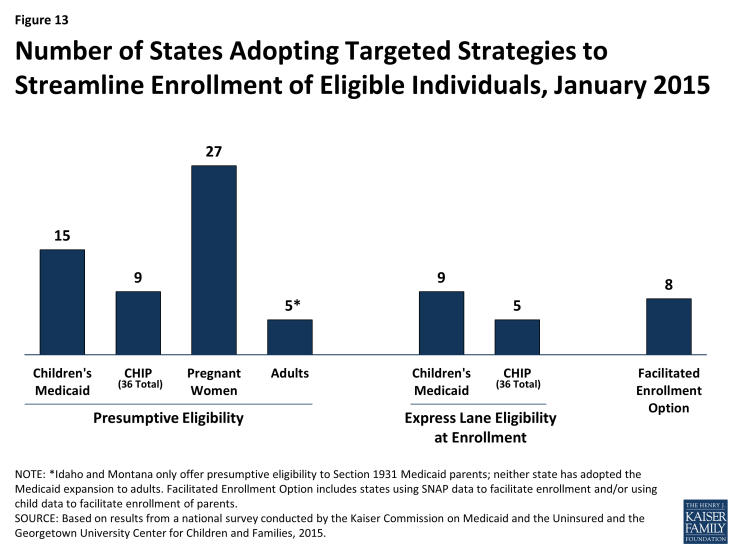

A range of additional streamlining options further facilitate enrollment of eligible individuals in some states. Under the longstanding presumptive eligibility option in Medicaid and CHIP, states can allow qualified entities to expedite access to coverage for children and pregnant women. The ACA allows states to expand this option to parents and other adults if the state offers it to children or pregnant women. States have taken mixed action with regard to providing presumptive eligibility. Since 2013, several states have eliminated presumptive eligibility for children (MA, MI and UT) or pregnant women (AR, DE, MA, MI, and OK), likely given that new data-driven enrollment processes are designed to enable faster eligibility determinations. Conversely, five states (ID, MT, NH, NJ and OH) have expanded presumptive eligibility to parents or other adults. Following this state action, as of January 2015, 15 states provide presumptive eligibility for children in Medicaid, 9 for children in CHIP, 27 for pregnant women, and 5 for adults (Figure 13). The ACA also establishes new authority for hospitals to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations, although states are in various stages of effecting this requirement. In addition, since 2009, states have had the option to utilize Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) to enroll children in Medicaid or CHIP based on eligibility findings from other programs, like SNAP. As of January 1, 2015, nine states use ELE to enroll children in Medicaid, while five use ELE to enroll CHIP-eligible children. In 2013, CMS offered states additional facilitated enrollment options, including using SNAP data to identify and enroll eligible individuals and using child enrollment data to expedite parent enrollment. To date, eight states have taken up one or both of these strategies, which analysis has shown contributed to success in enrolling newly eligible adults and children and reducing administrative costs.2 These options remain available for other states to take up moving forward.

Figure 13: Number of States Adopting Targeted Strategies to Streamline Enrollment of Eligible Individuals, January 2015

Renewal

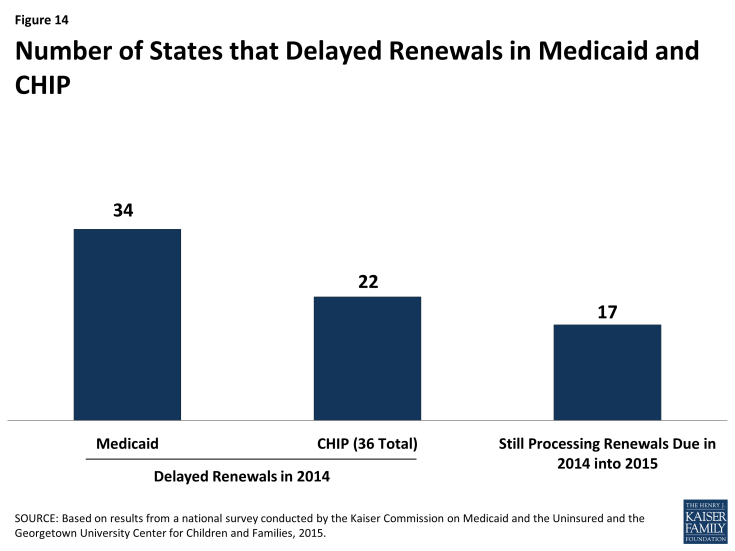

States are making progress adopting automated renewal processes, but transition work continues. Similar to enrollment processes, the ACA calls for new highly automated, paperless renewal processes for Medicaid and CHIP. When possible, states must use available data to renew coverage automatically (also called ex parte renewal). Many states are still implementing and transitioning to these new processes, given a range of challenges including developing system capacity to process automated renewals, transferring data for existing enrollees from old legacy systems to new systems, and creating notices for individuals. In the interim, a number of states are relying on mitigation strategies such as mailing forms to individuals to request the information needed to complete renewal. To ease the transition to new renewal procedures, CMS offered states the opportunity to temporarily delay renewals, an option which 34 states took up for Medicaid and 22 states took up in CHIP during 2014 (Figure 14). About half have completed all of their delayed renewals, although 17 states have extended some of these renewals into 2015. Continued work to address the challenges of adopting new automated renewal processes will be important for preventing coverage losses and gaps and supporting more stable coverage over time.

In July 2014, CMS offered states additional flexible renewal strategies. CMS clarified that states can continue to conduct renewals based on available information without collecting the additional information necessary to coordinate with Marketplace coverage, which includes tax-filing status and access to employer coverage. However, states can only affirmatively renew coverage using this approach and cannot deny coverage without collecting all required information. Additionally, states can receive expedited waiver approval from CMS to renew coverage using information from SNAP, as well as to facilitate renewals for enrollees with no change in circumstances that affect eligibility.

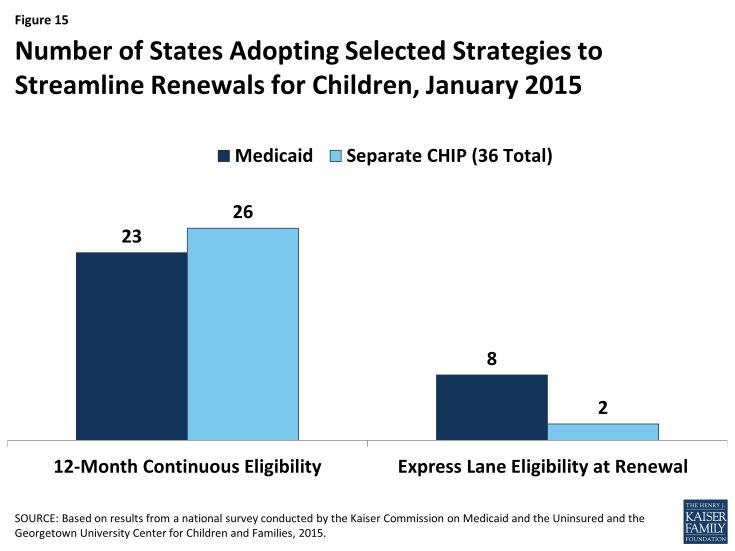

Some states are utilizing other policy options to boost retention and support stable coverage over time. Under the ACA, all states must conduct renewals once every 12 months. States can further support stable coverage and reduce churn resulting from small fluctuations in income by opting to provide 12-month continuous eligibility, which allows individuals to remain enrolled for a full year regardless of changes in circumstances. As of January 1, 2015, 23 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid, and 26 have adopted it in their separate CHIP programs (Figure 15). States also can extend 12-month continuous eligibility to parents and other adults under Section 1115 waiver authority, which New York has done for parents to provide consistent procedures for all enrolled family members. Another option available to states to streamline renewal is ELE, which eight states use to renew children’s Medicaid coverage and two states utilize for CHIP renewals. Massachusetts is also using ELE to renew parents in Medicaid under Section 1115 waiver authority.

Figure 15: Number of States Adopting Selected Strategies to Streamline Renewals for Children, January 2015

Eligibility and Enrollment Systems

In order to implement the new modernized, data-driven enrollment and renewal processes outlined in the ACA, most states needed to make major improvements to or build new Medicaid and CHIP eligibility determination systems, often replacing decades-old legacy systems. Harnessing technology within Medicaid and CHIP can enhance the consumer experience and improve the reliability, timeliness and administrative efficiency of eligibility determinations and ongoing case management for enrollees. To support system upgrades and builds, the federal government provided 90 percent federal funding for system design and development. This increased funding was initially set to expire at the end of 2015, but, in October 2014, CMS announced plans to extend the higher federal match permanently.1 The ongoing availability of enhanced funding will give states more time to phase in additional functionality and help systems stay current as technology evolves in the future. States have made significant progress developing efficient, interconnected eligibility and enrollment systems, but ongoing efforts will be needed to refine and enhance systems to fulfill the vision of the ACA.

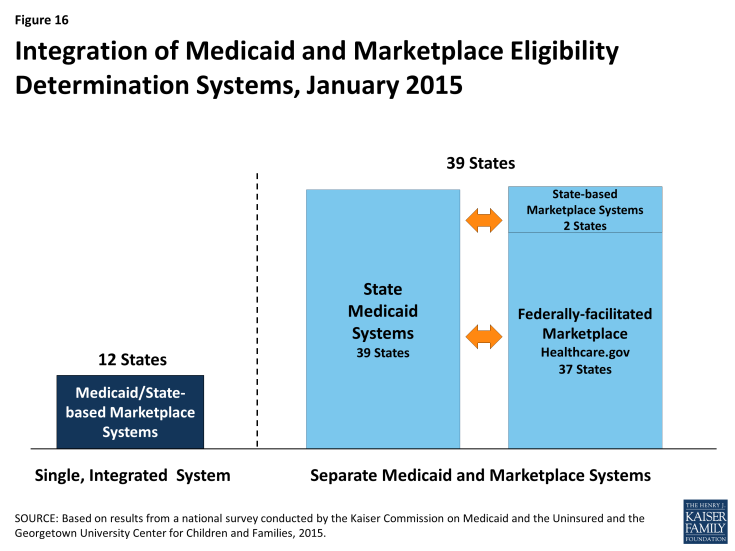

States have made varied choices with regard to the integration of their Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility determination systems, largely influenced by their Marketplace structure. All states must have a Medicaid eligibility determination system, but SBM states may operate a single, integrated system that makes eligibility determinations for both Medicaid and Marketplace coverage, which 12 states do. In the remaining 39 states, separate eligibility determination systems are used for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. These include two SBM states that have separate state-level systems, three SBM states that are relying on the FFM for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions, and all 34 FFM and Partnership Marketplace states (Figure 16). Nearly all states with a separate CHIP program (34 of 36) have integrated CHIP into their Medicaid eligibility determination system.

When systems are not integrated, coordination between Medicaid and Marketplace systems is key to smooth enrollment. The SBM states with a single integrated Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility determination system do not need to transfer accounts between systems to coordinate eligibility determinations across coverage programs, although, in some cases, transfers of data and additional actions must occur after the eligibility determination to complete enrollment. However, in states with separate systems, including all 37 states relying on the FFM for eligibility and enrollment functions, electronic data, known as account transfers, must be exchanged between systems to provide a coordinated, seamless enrollment experience for individuals, as envisioned by the ACA. Ten of the FFM states have authorized the federal system to make final Medicaid eligibility determinations, which can speed the enrollment process. Alternatively, 27 states allow the FFM only to assess rather than determine Medicaid eligibility. These states must review accounts transferred from the FFM and potentially check other data sources or gather additional information from applicants prior to making a final Medicaid eligibility determination. There were technical difficulties with Medicaid and Marketplace coordination during 2014 that contributed to some delays in Medicaid enrollment. The federal government and states have sought to address these issues for 2015, but the extra steps needed to determine eligibility, along with the higher volume of applications generated during open enrollment, may still result in backlogs in some states.2

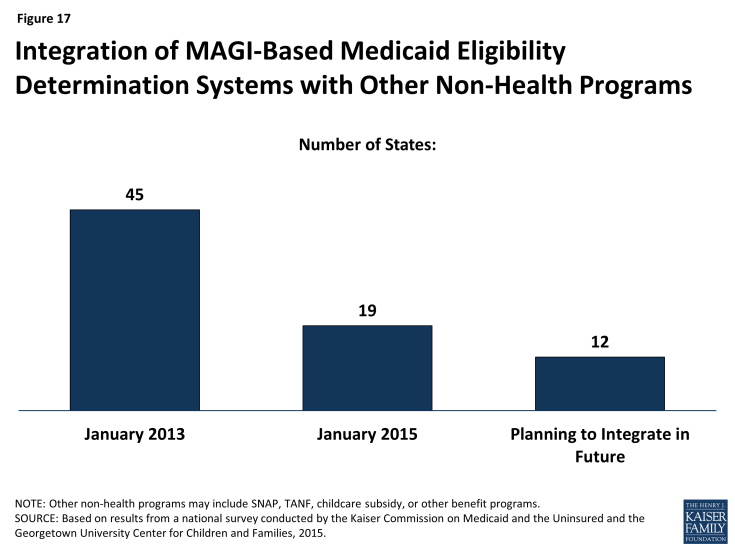

Many states delinked Medicaid eligibility determination systems from other benefit programs as they deployed new MAGI-based systems, but a number plan to reintegrate eligibility for other programs in the future. Prior to the ACA, the majority (45) of state Medicaid eligibility determination systems were integrated with other assistance programs, such as SNAP or TANF. As states implemented new ACA eligibility determination and enrollment processes for Medicaid and upgraded or built new eligibility systems, many delinked Medicaid from these other programs due to the large scale of the changes. As of January 1, 2015, 19 states maintain systems that administer eligibility for Medicaid and other benefit programs (Figure 17). However, this number will likely grow over time, as 12 states indicate that they plan to phase in other assistance programs in 2015 or beyond. These efforts are further supported by CMS’ intent to extend the opportunity for non-health programs to pay only the add-on costs associated with integrating into newly enhanced Medicaid systems through 2018.3

Figure 17: Integration of MAGI-Based Medicaid Eligibility Determination Systems with Other Non-Health Programs

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

Recognizing the limited family budgets of low-income individuals, federal rules set parameters in Medicaid and CHIP on the amount of premiums and cost-sharing, such as copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles, that states may charge (see Box 1). Consistent with federal rules, the findings presented below show that premiums and cost-sharing for selected services generally remain low in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 1, 2015. Even with flexibility to charge premiums and cost-sharing, many states limit charges in their programs to minimize barriers for enrollees in accessing care and reduce administrative burdens and complexities for state agencies.

Box 1: Premium and Cost-Sharing Rules for Medicaid and CHIP

The ACA did not make direct changes to premium and cost-sharing rules for Medicaid and CHIP, but its adjustments to eligibility thresholds impacted how some states assess premiums and cost-sharing. Specifically, the ACA’s establishment of a minimum threshold for children’s Medicaid eligibility at 138 percent of the FPL effectively raised the income level at which premiums and cost-sharing start in some states. All children, regardless of age, with family incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the FPL now fall under Medicaid’s premium and cost-sharing protections. As a result, the income threshold above which premiums begin for children increased to 138 percent of the FPL in seven states. Similarly, changes in eligibility thresholds resulted in an increase in the income level at which cost-sharing begins in 14 states that charge cost-sharing in CHIP but not Medicaid. Other states adjusted the income level at which cost-sharing begins to align with their MAGI-converted eligibility thresholds.2

Premiums

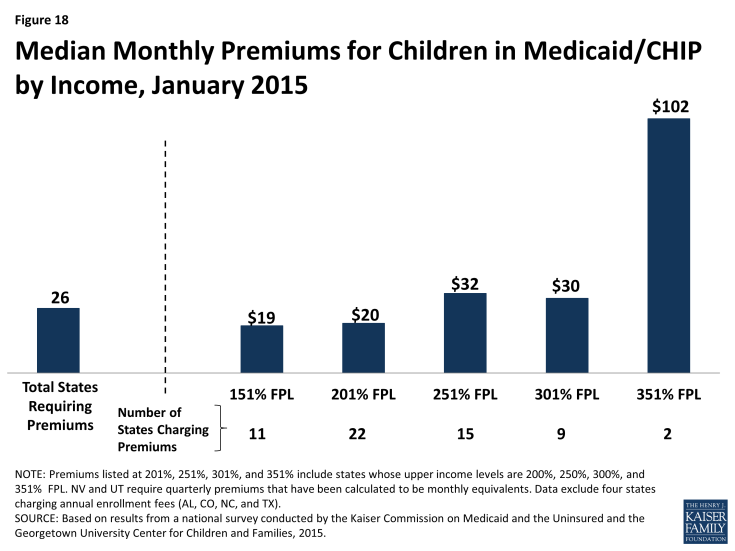

Overall, 30 states charge premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid or CHIP. This total includes three states (CA, MD and VT) that charge premiums for children in Medicaid with incomes above 150 percent of the FPL, 23 states that charge monthly or quarterly premiums in their CHIP programs, and four states that charge annual enrollment fees in CHIP. The greater prevalence of premiums and enrollment fees in CHIP reflects the relatively higher family incomes of children covered by the program as well as its more flexible premium rules. Among the 26 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums for children in Medicaid or CHIP, most (21) limit the charges to children in families with incomes at or above 150 percent of the FPL, including eight that only assess the charges at income levels at or above 200 percent of the FPL. Median premium amounts per child range from $19 at 151 percent of the FPL to $102 at 351 percent of the FPL, although only two states provide coverage at this income level (Figure 18). The ACA protects children’s coverage through 2019, and, thus, premium increases are permitted only if specific methods for raising premiums were approved in the state Medicaid or CHIP plan as of March 23, 2010.

There is variation across states in policies related to non-payment of premiums.3 If states charge premiums in Medicaid, they must offer a 60-day grace period before coverage can be cancelled for nonpayment. While unpaid premiums may result in termination of Medicaid coverage, states cannot require enrollees to repay premiums as a condition for re-enrollment, nor can they prevent eligible individuals from re-enrolling immediately. In CHIP, states are required to offer a minimum grace period of 30 days. Grace periods vary across the 23 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums in CHIP, with seven states providing the minimum 30-day grace period and 17 states providing grace periods of 60 days or longer. Following cancellations of coverage for nonpayment of premiums, states may delay re-enrolling former enrollees in CHIP coverage, but the ACA limits such lock-out periods to no more than 90 days. As of January 1, 2015, 13 of 23 states that charge monthly or quarterly premiums in their separate CHIP programs have lock-out periods. This count reflects newly established lock-out periods in eight states (IN, KS, LA, MA, NV, UT, VT and WA) and the elimination of lock-out periods in four states (CT, IL, OR, and WV) since January 2013. Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin also reduced their lock out periods for non-payment of premiums from six months to 90 days. In 16 states, families who have been dis-enrolled due to non-payment of premiums must reapply to re-enroll in coverage. Eight states allow families to receive retroactive coverage if they pay outstanding premiums.

In general, states do not charge low-income parents and other adults premiums in Medicaid. This reflects the fact that eligibility for parents and other adults is generally limited to levels below which premiums can be charged. However, four states (AR, IA, MI, and PA) have received Section 1115 waiver approval to impose monthly payments that are not otherwise permitted under federal rules for some adults covered through their Medicaid expansions. As of January 1, 2015, these payments had been implemented in Iowa and Michigan. Although the specific policies vary across the four states, payment of these monthly contributions is not always a condition of enrollment, and, in some cases, individuals do not have to make the payments if they participate in certain activities or obtain an exemption.

Cost-Sharing

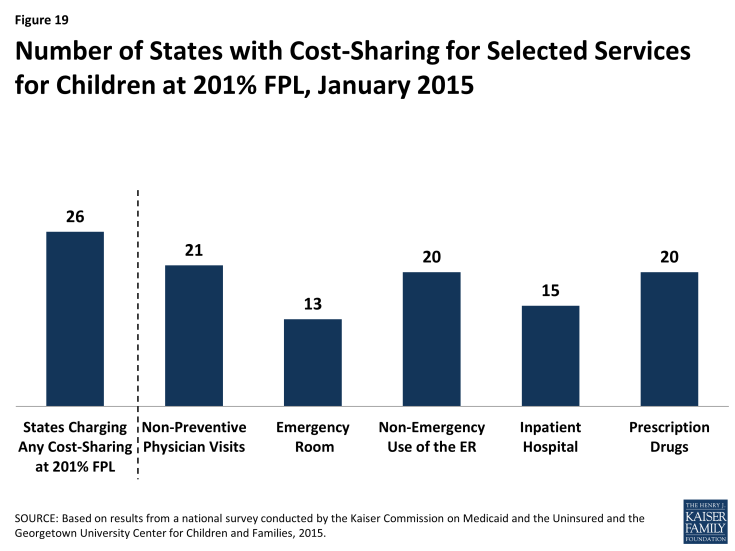

Overall 26 states charge cost-sharing for children in Medicaid or CHIP. Four states charge cost-sharing for children in Medicaid, while 24 of 36 states with separate CHIP programs charge cost-sharing, although cost-sharing requirements vary by income. Cost-sharing for children begins at or above 133 percent of the FPL in all of these states, except Tennessee, which assesses cost-sharing at lower income levels under Section 1115 waiver authority. Cost-sharing also varies by service type. For example, for a child with family income at 201 percent of the FPL, 21 states charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 13 charge for an emergency room visit, 20 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 15 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 20 have charges for prescription drugs, although, in some cases, charges only apply to brand name or non-preferred brand name drugs (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Number of States with Cost-Sharing for Selected Services for Children at 201% FPL, January 2015

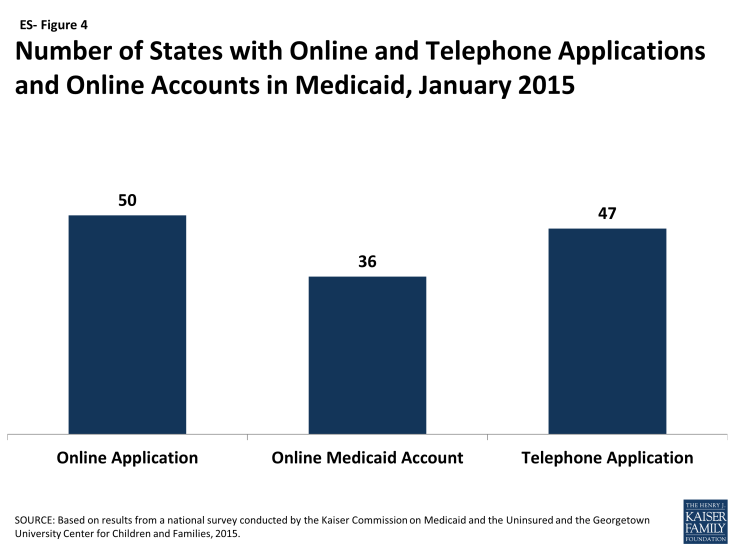

Most states (40) charge cost-sharing for Section 1931 parents in Medicaid and 20 of the 28 states that have expanded Medicaid have cost-sharing for expansion adults (Figure 20). Reflecting the low incomes of parents and adults covered by Medicaid, this cost-sharing is generally limited to nominal amounts. For parents, 24 states charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 20 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 27 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 39 charge for prescription drugs, although, in some cases, the charges only apply to brand name drugs. Among the 28 states with coverage for Medicaid expansion adults, 9 charge cost-sharing for a physician visit, 13 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 12 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 19 charge for prescription drugs.

Looking Ahead

Taken together, these findings show that, one year into implementation, the ACA has accelerated meaningful transformation of the Medicaid program, broadening it as a base of coverage for the low-income population and leading to substantial modernization of its enrollment processes and systems. There have been significant increases in eligibility levels for low-income adults in states that expanded Medicaid, but eligibility levels remain low in states that have not expanded, resulting in gaps in coverage. Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children and pregnant women remains strong across states. On the operational and systems side, many states have achieved notable progress toward realizing the ACA’s vision of a streamlined, technology-driven enrollment system, but work continues in many areas.

Looking ahead to 2015, state and federal officials will continue efforts to refine Medicaid and CHIP procedures and systems to move closer toward the ACA’s vision of a real-time, data-driven eligibility and enrollment experience. Enhancing information technology systems, implementing streamlined renewal processes, and improving coordination between Medicaid and the Marketplaces will be among the top priorities going forward. At the same time, other changes in Medicaid and the broader health care system, such as delivery and payment system reforms, CHIP reauthorization, and continued action related to the ACA, including the Supreme Court’s consideration of King v. Burwell regarding the provision of premium tax credits in FFM states, all have important implications for coverage. Following are key issues to consider looking ahead to 2015.

The Medicaid expansion to low-income adults will likely lead to continued gains in enrollment. Newly tracked Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment performance metric data released monthly by CMS show large gains in Medicaid enrollment across states since the initial open enrollment period for the Marketplaces began in October 2013.1 The data show that Medicaid expansion states have experienced significantly greater enrollment gains than states that have not yet expanded. However, there have been gains across nearly all states, reflecting increased enrollment among both adults made newly eligible by the expansion as well as individuals who were previously eligible but not enrolled who were reached through outreach and enrollment efforts. Emerging data also suggest that these gains in Medicaid enrollment are leading to reductions in the number of uninsured. Although data from the large federal population-based surveys are not yet available to measure changes in uninsured rates, several recent private surveys have consistently shown corresponding reductions in the uninsured rate since implementation of the ACA, and one study found that the uninsured rate dropped by 4 percentage points in expansion states, compared to 1.4 percentage points in non-expansion states.2 However, gaps in coverage remain in the 23 states that have not expanded Medicaid, leaving nearly four million poor adults without access to an affordable health coverage option. Moreover, continued progress in adopting streamlined renewal procedures will be important for preventing potential coverage losses or gaps over time.

Additional states may move forward with the Medicaid expansion. There is no deadline by which states must decide to implement the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults and debate continues in several states. However, the 100 percent federal financing for newly eligible individuals begins to phase down after 2016 to 90 percent by 2020. To date, a limited number of states have obtained or are seeking approval through Section 1115 waivers to implement the expansion in ways that extend beyond the flexibility provided by the law. Looking ahead, more states may pursue alternative models through waivers to extend coverage with federal dollars. These waivers are intended to be research and demonstration projects, and, as such, it will be important to evaluate their impacts to provide greater insight into serving Medicaid’s low-income beneficiaries. What happens with Medicaid waivers between 2014 and 2016 also will be important to inform the use of the new state innovation waiver authority available in 2017, which will allow states waive certain Marketplace provisions and may be combined with Medicaid waivers to implement state-specific health reform approaches.

As of 2015, states may also expand coverage through a new option established by the ACA, the Basic Health Program (BHP). In March 2014, CMS published final regulations that describe how states can provide coverage through a BHP for individuals who do not qualify for Medicaid or CHIP but have income under 200 percent of the FPL. This option allows states to finance a state-run program with 95 percent of the federal funding these enrollees would receive for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions. As noted, Minnesota became the first state to implement a BHP and converted existing Medicaid coverage for enrollees with incomes between 138 and 200 percent of the FPL to a BHP. In addition, New York has indicated plans to pursue a BHP.

States will continue work to advance enrollment and renewal processes and enhance their system functionality, supported by ongoing 90 percent federal funding for Medicaid eligibility and enrollment systems. High-performing eligibility and enrollment systems are central to moving toward a paperless process for determining eligibility for new applicants and keeping eligible enrollees covered at renewal. While challenges exist to achieving real-time, data-driven eligibility determinations, the shift from paper documentation to electronic sources will improve over time as states use the enhanced federal funds to harness technology and secure access to more data sources. Moreover, the funding will help support continued system enhancement to move states closer toward the automated, electronic data-driven renewal processes called for in the ACA, as states work to resolve challenges transitioning to new renewal processes and phase out mitigation strategies. Similarly, continued work will be important for ensuring smooth account transfers between Medicaid and Marketplaces to assure “no wrong door” access to coverage and prevent delays in enrollment. In addition, the three-year extension of flexibility to charge other public benefits programs only the added cost of consolidating eligibility determinations into the new Medicaid systems will support state efforts to phase-in integration of other programs.

Lastly, 2015 will be a pivotal year for children’s health coverage as CHIP funding will not extend beyond September 2015 without congressional action. Together, CHIP and Medicaid have led the way to historically high levels of coverage for children. When CHIP was enacted, it spurred improvements in children’s coverage, which have served as a catalyst for many of the innovations in streamlining eligibility and enrollment that were adopted by the ACA. The future of CHIP will have important implications for children’s coverage. As debates over extended funding for CHIP advances, it will be important to consider barriers to coverage as well as differences in coverage between CHIP and the Marketplace to understand the implications of CHIP funding decisions.

The authors extend our sincere appreciation to the many state officials who generously shared their time and expertise with us to participate in this survey and help us to understand the nuances of their programs. This report would not be possible without them, and we greatly value their contributions during such a busy time. We also extend our thanks to Martha Heberlein, formerly with the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, for her work on this report.

Tables

Table 1: Adult Income Eligibility Limits as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level

Table 3: Waiting Period for CHIP Enrollment

Table 4: Optional Medicaid and CHIP Coverage for Children

Table 5: Medicaid and CHIP Coverage for Pregnant Women

Table 6: Online and Telephone Medicaid Applications

Table 7: Online Account Capabilities for Medicaid

Table 8: Income Verification Procedures Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application

Table 9: Non-Financial Eligibility Criteria Verification Procedures Used by Medicaid Agencies

Table 10: Adoption of Targeted Strategies to Streamline Enrollment of Eligible Individuals

Table 11: Renewal Delays and Targeted Strategies to Streamline Renewal

Table 12: Integration between Eligibility Systems for Medicaid and Other Programs

Table 13: Premium, Enrollment Fee, and Cost-Sharing Requirements for Children

Table 14: Premiums and Enrollment Fees for Children at Selected Income Levels

Table 15: Disenrollment Policies for Non-Payment of Premiums in Children’s Coverage

Table 16: Cost-Sharing Amounts for Selected Services for Children at Selected Income Levels

Table 17: Cost-Sharing Amounts for Prescription Drugs for Children at Selected Income Levels

Table 18: Premium and Cost-Sharing Requirements for Selected Services for Section 1931 Parents

Table 19: Cost-Sharing for Selected Services for Medicaid Expansion Adults

Endnotes

Executive Summary

Indiana, Oklahoma, and Utah provide more limited coverage to some childless adults under Section 1115 waiver authority.

R. Garfield, et al., “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in State that Do Not Expand Medicaid – An Update,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2014.

J. Guyer, T. Schwartz, S. Artiga, “Fast Track to Coverage: Facilitating Enrollment of Eligible People into the Medicaid Expansion, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2013.

Smith, V., et al.., “Medicaid in an Era of Health and Delivery System Reform: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 14, 2014, https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-in-an-era-of-health-delivery-system-reform-eligibility-and-enrollment/

The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP,” June 2014.

Introduction

As in past reports, information is not included for low income seniors or people with disabilities covered by Medicaid.

Report

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

The ACA established new standards for determining eligibility based on tax law in order to align coverage across the insurance affordability programs, including Medicaid, CHIP and subsidies in the health insurance marketplaces. MAGI rules establish specific guidelines for counting income and household size, although there are some exceptions in determining Medicaid eligibility only. States can no longer use asset tests in determining eligibility and were required to convert their pre-ACA eligibility levels accounting for the use of income disregards and deductions to the new MAGI standards, which were implemented on January 1, 2014. A standard five-percentage point disregard applies to the upper eligibility limits in determining MAGI-based eligibility. MAGI rules apply only to coverage for children, pregnant women, parents and the new expansion adult group, not to seniors or the disabled.

The newly elected governor in Pennsylvania has indicated plans to move to the state option for expansion.

Indiana, Oklahoma, and Utah provide more limited coverage to some childless adults under Section 1115 waiver authority.

R. Garfield, et al., “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in State that Do Not Expand Medicaid – An Update,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2014.

Enrollment and Renewal Processes

J. Edwards, et al., “Reducing Paperwork to Improve Enrollment and Retention in Medicaid and CHIP,” Medical Institute at United Hospital Fund, October 2009.

J. Guyer, T. Schwartz, S. Artiga, “Fast Track to Coverage: Facilitating Enrollment of Eligible People into the Medicaid Expansion, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November 2013.

Eligibility and Enrollment Systems

CMS announced its plan in a letter dated October 28, 2014 from Cindy Mann, Director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, to the American Public Human Services Association and the National Association of Medicaid Directors. http://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Letter-to-APHSA-and-NAMD-from-Cindy-Mann-10-28-14-.pdf

Smith, V., et al.., “Medicaid in an Era of Health and Delivery System Reform: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 14, 2014, https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-in-an-era-of-health-delivery-system-reform-eligibility-and-enrollment/

Letter from Cindy Mann, October 28, 2014, op cit.

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

CHIP rules also limit the amounts that may be charged to enrollees. For families earning less than 150 percent of FPL, premiums cannot exceed $19 per month depending on income and family size while co-payments and other cost-sharing limits are slightly higher than Medicaid. No limits apply to families with income above 150 percent of the FPL, except the total annual cost-sharing cap of five percent of income, which applies to all CHIP enrollees.

An interim study published in November 2013 compares the pre-ACA eligibility levels with the MAGI-converted levels. For more information see, “Getting into Gear for 2014: Shifting New Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Policies into Drive.”

If states charge premiums in Medicaid, they must provide a 60-day grace period because cancelling coverage due to nonpayment of premiums. Additionally, they are prohibited from locking beneficiaries out of coverage or making them repay outstanding amounts in order to re-enroll. See 42 CFR 447.55.

Looking Ahead

CMS posts state-by-state, monthly Medicaid and CHIP application and enrollment data, which can be found at http://medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/medicaid-and-chip-application-eligibility-determination-and-enrollment-data.html.

L. Clemans-Cope, et al., “Increase in Medicaid under the ACA Reduces Uninsurance, According to Early Estimates,” The Urban Institute, June 25, 2014.