Implications of the Expiration of Medicaid Long-Term Care Spousal Impoverishment Rules for Community Integration

Introduction

Seniors and people with disabilities or chronic illnesses may need long-term services and supports (LTSS) for help with self-care tasks (such as eating, bathing, or dressing) and household activities (such as preparing meals, managing medication, or housekeeping). Medicaid is the primary payer for LTSS, covering over half of national spending on nursing home care and home and community-based services (HCBS) as of 2017.1 To financially qualify for Medicaid LTSS, an individual must have low income and limited assets. When one spouse in a married couple needs LTSS, Medicaid spousal impoverishment rules protect some income and assets to support the other spouse’s living expenses, in an effort to prevent her “financial devastation from paying the high cost of [her spouse’s] nursing home care.”2

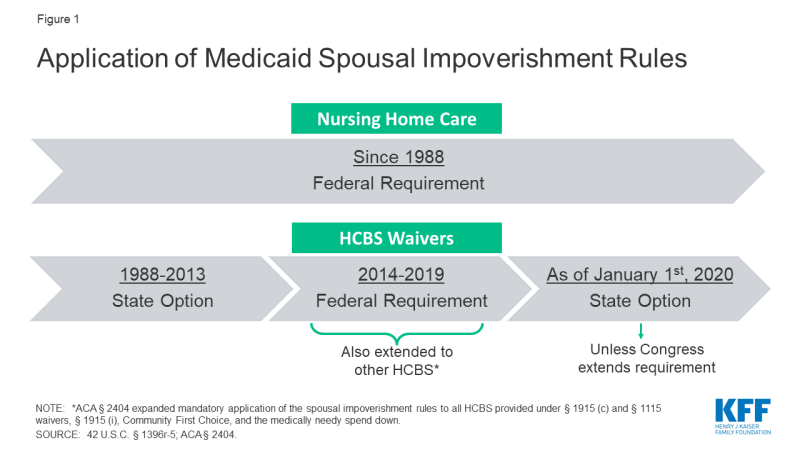

Since Congress enacted the spousal impoverishment rules in 1988, federal law has required states to apply them when a married individual seeks nursing home care.3 Prior to 2014, states had the option to apply the rules when a married individual sought home and-community based waiver services.4 However, from January 1, 2014 through December 31, 2019, Section 2404 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has required states to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS waivers.5 Section 2404 also expanded the spousal impoverishment rules to the Section 1915 (i) HCBS state plan option, Community First Choice (CFC) attendant care services and supports, and individuals eligible through a medically needy spend down. If Congress does not reauthorize Section 2404, the spousal impoverishment rules will revert to a state option for HCBS waivers and will not apply to other HCBS, as of January 1, 2020 (Figure 1).

This issue brief answers key questions about the spousal impoverishment rules,6 presents new data from a 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) 50-state survey about state policies and future plans in this area, and considers the implications if Congress does not extend Section 2404.

Key Questions About Medicaid LTSS Spousal Impoverishment Rules

1. What are the general Medicaid LTSS financial eligibility rules?

Federal law limits Medicaid LTSS eligibility to people with low incomes and limited assets. At minimum, states generally must cover nursing home care for people who have qualifying functional needs and receive federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits7 ($771 per month for an individual, and $1,157 for a couple in 2019).8 States can choose to adopt the “special income rule,” to increase the Medicaid nursing home income limit to 300% of SSI ($2,313 per month for an individual in 2019),9 and 43 states do so in 2018.10 States also can choose to apply the “special income rule” when determining Medicaid financial eligibility for people receiving HCBS under a waiver, and all but one of the states using the “special income rule” elect this option to expand HCBS financial eligibility; this eligibility pathway known as the “217-group.”11 Additionally, people who qualify for Medicaid institutional LTSS or HCBS under the “special income rule” typically are subject to an asset limit, and most states apply the SSI asset limits of $2,000 for an individual, and $3,000 for a couple.

Once eligible for Medicaid LTSS, individuals generally must contribute a portion of their monthly income to the cost of their care. These “post-eligibility treatment of income” (PETI) rules apply to both nursing home services and HCBS waivers. For those in nursing homes, a small “personal needs allowance” is permitted to pay for items not covered by Medicaid, such as clothing;12 the federal minimum personal needs allowance is $30 per month and the state median was $50 per month in 2018.13 Individuals in the “217-group” are subject to PETI under HCBS waivers and may have a higher “maintenance needs allowance,” recognizing that individuals living in the community must pay for room and board. There is no federal minimum for HCBS maintenance needs; instead, states may use any amount as long as it is based on a “reasonable assessment of need” and subject to a maximum that applies to all enrollees under the waiver.14

2. What policy considerations led Congress to enact the spousal impoverishment rules?

Congress created the spousal impoverishment rules in 1988, to protect a portion of a married couple’s income and assets to support the “community spouse’s” living expenses when the other spouse sought Medicaid LTSS. The spousal impoverishment rules supersede rules that would otherwise require eligibility determinations to account for a spouse’s financial responsibility for a Medicaid applicant or beneficiary.15 They were enacted “in response to evidence that at-home spouses – typically elderly women with little or no income of their own – faced poverty and a radical reduction in their standard of living before their spouses living in a nursing home could qualify for Medicaid.”16 Prior to the spousal impoverishment rules, “married individuals requiring Medicaid-covered LTSS were commonly faced with either forgoing services or leaving the spouse still living at home with little income or resources.”17

Concerns about potentially financially devastating LTSS costs that motivated Congress to add the spousal impoverishment rules to Medicaid 30 years ago remain relevant today. LTSS costs are difficult for most people to afford out-of-pocket, and private insurance coverage of LTSS is limited. In 2019, a year of nursing home care averages over $90,000; average annual home health aide services cost over $52,000; and average annual adult day health care services total nearly $20,000.18 As in 1988, the high cost of LTSS “can rapidly deplete the lifetime savings of elderly couples”19 today. The spousal impoverishment rules “help ensure. . . that community spouses are able to live out their lives with independence and dignity.”20 While the amounts protected under the rules (discussed below) might be considered “quite modest or even inadequate to sustain the at-home spouse’s accustomed standard of living, they far exceed the income and asset levels that may be retained in the case of unmarried recipients of Medicaid long-term care services”21 (described above, e.g., typically $2,000 in countable assets and a minimum of $30 monthly personal needs allowance for nursing home enrollees).

3. How do the spousal impoverishment rules affect Medicaid LTSS financial eligibility?

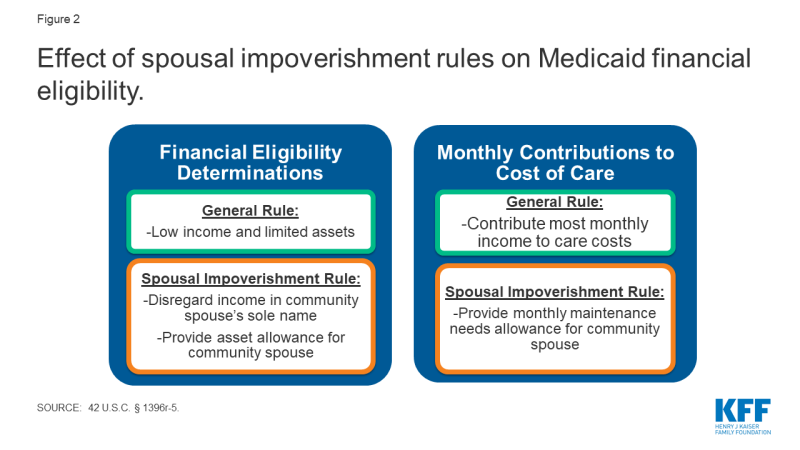

Since 1988, Congress has required states to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to long-term nursing home services to provide financial support for the “community spouse.”22 Specifically, states must disregard a portion of income and assets at two points when a married individual is seeking nursing home services: (1) when determining and renewing the individual’s Medicaid financial eligibility; and (2) when determining the individual’s monthly required contribution to his care costs under the PETI rules (Figure 2). The rules apply to long-term nursing home stays, which are those expected to last at least 30 consecutive days.23 The spousal impoverishment rules apply when a married individual seeks or receives Medicaid LTSS, and his spouse is not in a nursing home or other medical institution.24 The rules do not apply when both spouses seek long-term Medicaid nursing home care.25 The amounts protected under the spousal impoverishment rules are updated annually and are in addition to the general Medicaid LTSS income and asset limits described above. Box 1 provides additional detail about how protected amounts are determined under the rules.

Box 1: General Application of Medicaid Spousal Impoverishment Rules26

Income. When determining financial eligibility for a married individual seeking Medicaid LTSS,27 and when determining his required contribution from monthly income to the cost of care,28 any income in the “community spouse’s” sole name is not deemed available to the Medicaid spouse. Additionally, when determining the required contribution from monthly income to the cost of care, the starting point is that half of any income in the couple’s joint name is deemed available to the Medicaid spouse.29 The rules also provide for a “monthly maintenance needs allowance” (MMNA) for the community spouse, subject to both minimum and maximum limits.30 If the “community spouse’s” sole income, plus half of the couple’s joint income, is less than the minimum MMNA, the “community spouse” can retain additional income, enough to reach the minimum. The minimum MMNA is 150% FPL ($2,057.50 per month for a household of two in 2019).31 The “community spouse’s” MMNA cannot exceed a maximum limit ($3,160.50 in 2019).32

Assets. When determining Medicaid LTSS financial eligibility, the starting point is that half of the couple’s assets (including any countable assets in which either or both spouses have an ownership interest at the time of the Medicaid spouse’s most recent period of continuous institutionalization33) potentially can be retained by the “community spouse.34 The rules also provide for a “community spouse resource allowance” (CSRA), subject to minimum and maximum limits.35 If the “community spouse’s” half of the assets is less than the minimum CSRA ($25,284 in 2019; and higher at state option), the Medicaid spouse can transfer to her enough assets to reach the minimum CSRA. If the “community spouse’s” half of the assets exceeds the maximum CSRA ($126,420 in 2019), she can retain only the amount up to the maximum, with remaining assets considered available to the Medicaid spouse.36 After Medicaid eligibility is established, none of the “community spouse’s” assets are deemed available to the Medicaid spouse.37

From the rules’ creation in 1988, until ACA Section 2404 took effect in January 2014, states had the option to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS waivers.38 Specifically, states could choose whether to apply the rules to HCBS waivers in two instances: first, states could decide whether to apply the rules when determining and renewing financial eligibility under HCBS waivers for the “217-group.” These are individuals for whom states have opted to expand the minimum Medicaid LTSS financial eligibility limits under the “special income rule” (described above), who would be eligible under the Medicaid state plan if institutionalized, meet an institutional level of care, and would be institutionalized if not receiving waiver services. The option to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS waivers is specifically limited to the 217-group, even though states also can include people eligible through other Medicaid eligibility pathways in their HCBS waivers.39 Second, if states apply the spousal impoverishment rules when determining and renewing Medicaid financial eligibility for the 217-group under HCBS waivers, they also can opt to apply the rules to this group when determining any required monthly contribution from income to their cost of care under the PETI rules (described above). The 217-group is the only Medicaid HCBS population subject to PETI.

Prior to Section 2404 taking effect in 2014, most, but not all states, opted to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS waivers. In 2009 (the most recent year for which data are available prior to 2014), five states (Alabama, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and West Virginia) chose not to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS waivers, and these data were not reported for one state (Illinois).40

4. How Did ACA Section 2404 change the Medicaid spousal impoverishment rules?

Section 2404 currently requires states to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to Medicaid HCBS waivers from January 1, 2014 through December 31, 2019. Under the ACA, Section 2404 was set to expire on December 31, 2018, but Congress has temporarily extended the provision first through March 31, 2019, then through September 30, 2019, and most recently through December 31, 2019. Section 2404 removes the state option for applying the rules to HCBS waivers and instead makes the rules mandatory for determining both financial eligibility and PETI when a married individual seeks Medicaid home and community-based waiver services.41

Additionally, Section 2404 expands the types of HCBS to which states must apply the spousal impoverishment rules from 2014 through 2019. First, Section 2404 applies the spousal impoverishment rules to all individuals under Section 1915 (c) HCBS waivers, not just the 217-group. Section 2404 also applies the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS provided under Section 1115 waivers. Finally, Section 2404 requires states to apply the rules when determining Medicaid financial eligibility for HCBS provided through additional authorities, including the Section 1915 (i) state plan option, CFC attendant care services and supports, and medically needy/spend down pathways. Table 1 summarizes federal requirements and state options to apply the spousal impoverishment rules over time.

| Table 1: Federal Requirements and State Options to Apply Medicaid Spousal Impoverishment Rules | |||

| LTSS Authority | 1988-2013 | 2014-2019, under Section 2404 | As of Jan. 1, 2020, unless Section 2404 reauthorized |

| Institutional care | |||

| Nursing homes | Required | Required | Required |

| Medical institutions | Required | Required | Required |

| HCBS | |||

| 217-group in Section 1915 (c) waivers | State option* | Required | State option* |

| Other groups in Section 1915 (c) waivers | Not allowed** | Required | Not allowed** |

| HCBS under Section 1115 waivers | Not allowed** | Required | Not allowed** |

| Section 1915 (i) state plan HCBS | Not allowed** | Required | Not allowed** |

| Community First Choice | Not allowed** | Required | Not allowed** |

| Medically needy/spend down | Not allowed** | Required | Not allowed** |

| NOTES: *States opt whether to apply the rules to financial eligibility for the 217-group, and if so, separately opt whether to also apply the rules to that group’s PETI. **States may obtain § 1115 waivers to apply the rules to individuals other than the 217-group. SOURCE: 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-5; ACA § 2404. | |||

5. What are the implications if ACA Section 2404 expires in December 2019?

If Congress does not extend Section 2404, application of the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS waivers will return to a state option as of January 1, 2020,42 and will no longer apply to the other HCBS authorities (Table 1). Without Section 2404, states would have to obtain a Section 1115 waiver to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to HCBS waiver enrollees other than the 217-group, Section 1915 (i) state plan HCBS, CFC, or individuals eligible through a spend down.43 Facing impending expiration of the rules first in December 2018, and again in April 2019, September 2019, and December 2019, CMS has issued guidance directing states to take the following actions if Section 2404 expires: (1) redetermine financial eligibility, without applying the spousal impoverishment rules, for all individuals receiving HCBS under Section 1915 (i) and CFC, and for those eligible under HCBS waivers (other than the 217-group if the state elects the option); (2) recalculate PETI for individuals receiving services under HCBS waivers, (other than the 217-group if the state elects the option); and (3) stop applying the rules to new Medicaid HCBS applicants (other than the 217-group if the state elects the option.44

If Section 2404 expires, over three-quarters (40 of 51) of states plan to continue applying the spousal impoverishment rules to at least some HCBS waiver populations (the 217-group), while five states’ plans were unknown at the time of our survey.45 Among the 40 states with plans to continue the spousal impoverishment rules for 217 waiver groups, all will apply them to eligibility determinations, 30 states will apply them to PETI, and 29 states will apply them to both determinations. Some state responses varied by waiver program. For example, 14 states were uncertain of continuation plans for at least one HCBS waiver.46 If the Section 2404 requirement expires, states will have the option to continue to apply the rules to the 217-group covered under Section 1915 (c) HCBS waivers.

Thirteen states already have or will seek a Section 1115 waiver to allow them to continue to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to non-217-group HCBS waiver enrollees, while 14 states will not seek such a waiver. Specifically, three states (AL, NV, OK) will seek a new Section 1115 waiver to continue to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to non-217 group waiver enrollees, and 10 states with existing Section 1115 waivers noted that this authority is included under their current waivers and will continue.47 By contrast, 14 states will not seek a Section 1115 waiver to continue the policy for non-217-group waiver enrollees.48 Sixteen states’ plans in this area were undecided at the time of our survey.49

Two of 11 states plan to continue applying the spousal impoverishment rules to Section 1915 (i) state plan HCBS enrollees if Section 2404 expires. These states (IA and NV) will seek a Section 1115 waiver to authorize this policy. By contrast, five states do not plan to continue applying the spousal impoverishment rules to Section 1915 (i) state plan HCBS if Section 2404 expires (CA, CT, ID, IN, TX). One state’s plans in this area were undecided (OH).50

None of the eight states offering CFC attendant services reported plans to continue applying the spousal impoverishment rules to CFC enrollees if Section 2404 expires.51 If Section 2404 expires, states would have to obtain a Section 1115 waiver to continue applying the spousal impoverishment rules to CFC enrollees. California, Oregon, and Washington would not seek such a waiver, while Connecticut, Maryland, Montana, and Texas were undecided.

Fourteen states report that the expiration of Section 2404 would have an impact on financial eligibility for individuals currently enrolled under HCBS waivers.52 Among these states, 10 expected that fewer individuals would be eligible for waiver services;53 five expected that more individuals would have a higher share of cost requirement under the PETI rules;54 and five expected that at least some waiver enrollees potentially would have to move to institutions due to loss of HCBS eligibility.55 Michigan indicated that the expiration of spousal impoverishment protections would result in 3,000 fewer individuals eligible under an HCBS waiver serving seniors and adults with physical disabilities. Without Section 2404, the spousal impoverishment rules will revert to a state option for HCBS waivers and will no longer apply to HCBS provided under other Medicaid authorities, unless states obtain a Section 1115 waiver, as of January 1, 2020.

Eight states report that the repeated temporary extensions of Section 2404 to date have affected the state and/or HCBS waiver enrollees. Among these states, six indicated confusion among waiver enrollees,56 and five noted increased staff workload.57 One state reported that state staff were unable to focus on other priorities due to the need to redetermine waiver eligibility and PETI in advance of the expiration date,58 while two states reported other impacts.59 Each time that the date on which Section 2404 was set to expire approached, states must redetermine enrollees’ financial eligibility, and if applicable PETI, without applying the spousal impoverishment rules, and send notice of any changes to enrollees before the expiration date, according to the CMS guidance described above. At minimum, states must do this for non-217 waiver enrollees, Section 1915 (i) enrollees, and CFC enrollees. States also must do this for the 217-group if they do not elect the option to continue to apply the rules. Then, each time after Congress enacted another temporary extension, states had to notify enrollees that the anticipated changes would not take effect, redetermine financial eligibility and PETI, this time applying the spousal impoverishment rules, and again send enrollees notice of any changes. This cycle has been repeated for scheduled expirations in December 2018, April 2019, September 2019, and December 2019,

Applying the same financial eligibility rules to Medicaid nursing facility care and HCBS helps alleviate bias in favor of institutional care.60 If financial eligibility limits are less stringent for nursing home care than for HCBS, an individual in need of LTSS may qualify only for institutional care. Even if an individual financially qualifies for both nursing home care and HCBS, he may be incentivized to choose nursing home care if that option will protect additional income and assets to support his spouse at home, due to differential application of the spousal impoverishment rules.

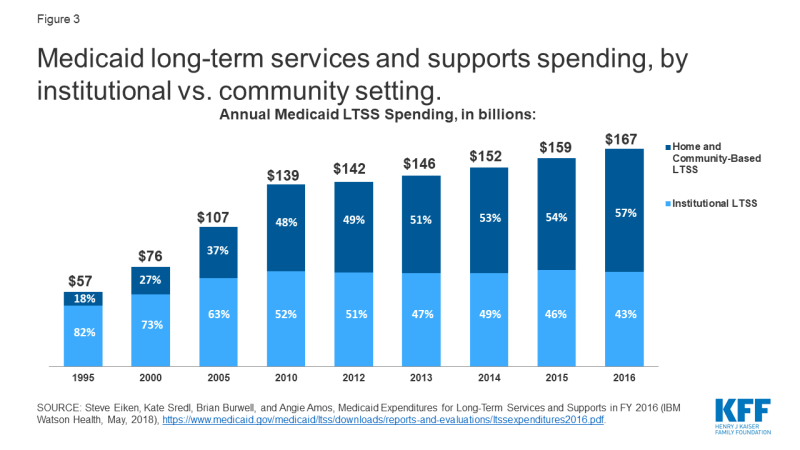

Applying more stringent income and asset rules to HCBS, compared to nursing home care, could impact the progress that states have made in expanding access to HCBS. The share of Medicaid LTSS spending devoted to HCBS instead of institutional care has been steadily increasing in recent decades. A majority of Medicaid LTSS spending went to HCBS for the first time in 2013, and reached 57% in 2016 (Figure 3). Although not required by federal Medicaid law, states have an independent community integration obligation under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) when administering services, programs, and activities.61 The Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision found that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities is illegal discrimination under the ADA, and Medicaid plays a key role in helping states meet their community integration obligations.62 Applying financial eligibility rules to HCBS that are more restrictive than those for institutional care could be challenged under the ADA, even if permitted by Medicaid law.

Figure 3: Medicaid long-term services and supports spending, by institutional vs. community setting.

Looking Ahead

Congress could consider legislation to extend Section 2404 in the coming weeks, before the provision expires at the end of December 2019. There does not appear to be a substantive debate over the issue like with other health programs, but there are always competing demands for federal funding. Section 2404’s original expansion of the spousal impoverishment rules in the ACA likely was time limited due to an effort to control costs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated the cost of the temporary extension of Section 2404 at $22 million for January through March 2019 at $22 million63 and $46 million for April through September 2019.64 CBO estimated that a longer-term extension, for 5 years from October 2019 through March 2024, would cost $331 million;65 Congress subsequently amended this bill to extend the rules from October through December 2019.

If reauthorized, the rules would provide stability and continuity for enrollees receiving HCBS and for states administering Medicaid eligibility determinations and renewals, while increasing federal and state budgetary costs over and above the current baseline. If Section 2404 expires, several states have indicated their plans to continue to apply the spousal impoverishment rules to some or all HCBS waivers are unknown. Though most states are planning to continue to apply the rules at this time, without Section 2404 or a similar requirement, states could stop doing so at any time by submitting an HCBS waiver amendment.66 Additionally, without Section 2404, states lack legal authority to apply the rules when determining financial eligibility for HCBS under other authorities, including waiver enrollees other than the 217-group, Section 1915 (i), CFC, and spend down pathways, and would have to devote time and resources to obtaining and administering a Section 1115 waiver to be able to treat financial eligibility for all HCBS equally.67 To date, few states plan to seek such a waiver. Applying different Medicaid financial eligibility rules to institutional LTSS and HCBS could affect states’ progress in expanding access to HCBS, rebalancing LTSS spending, and promoting community integration.

| Table 2: States’ Application of Spousal Impoverishment Rules to Medicaid HCBS | |||||

| State | Applied to Waivers in 2009 | Plans To Apply After § 2404 Expires in Dec. 2019 To: | |||

| 217 Waiver Groups | Non-217 Waiver Groups | § 1915 (i) HCBS* | CFC* | ||

| Alabama | No | Yes | Yes | ||

| Alaska | Yes | Unknown | Undecided | ||

| Arizona | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Arkansas | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| California | Yes | Yes | Undecided | No | No |

| Colorado | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Connecticut | Yes | Yes | No | No | Undecided |

| Delaware | Yes | Yes | Yes | No response | |

| DC | Yes | Yes | No response | No response | |

| Florida | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Georgia | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Hawaii | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Idaho | Yes | Yes | Undecided | No | |

| Illinois | No response | No response | No response | ||

| Indiana | Yes | Yes | Undecided | No | |

| Iowa | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Kansas | Yes | Unknown | Undecided | ||

| Kentucky | Yes | Yes | Undecided | ||

| Louisiana | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Maine | Yes | No response | No response | ||

| Maryland | Yes | Yes | No | Undecided | |

| Massachusetts | No | No response | No response | ||

| Michigan | Yes | Unknown | Undecided | ||

| Minnesota | Yes | Yes | No response | ||

| Mississippi | Yes | Yes | No | No response | |

| Missouri | Yes | Yes | Undecided | ||

| Montana | Yes | Yes | Undecided | Undecided | |

| Nebraska | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Nevada | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| New Hampshire | No | No response | No response | ||

| New Jersey | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| New Mexico | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| New York | No | No response | Undecided | No response | |

| North Carolina | Yes | No response | No response | ||

| North Dakota | Yes | Yes | Undecided | ||

| Ohio | Yes | Yes | No | Undecided | |

| Oklahoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Oregon | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Pennsylvania | Yes | Yes | Undecided | ||

| Rhode Island | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| South Carolina | Yes | Yes | Undecided | ||

| South Dakota | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Tennessee | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Texas | Yes | Unknown | Undecided | No | Undecided |

| Utah | Yes | Unknown | Undecided | ||

| Vermont | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Virginia | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Washington | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| West Virginia | No | Yes | No response | ||

| Wisconsin | Yes | Yes | Undecided | ||

| Wyoming | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| TOTAL ELECTING WAIVER/STATE PLAN OPTION | All 50 states and DC offer at least 1 waiver | 11 states | 8 states | ||

| APPLICATION OF SPOUSAL IMPOVERISHMENT | 45 yes, 5 no, 1 no response | 40 yes, 5 unknown, 6 no response | 13 yes, 14 no, 16 undecided, 8 no response | 2 yes, 5 no, 1 undecided, 3 no response | 0 yes, 3 no, 4 undecided, 1 no response |

| NOTES: *Blank cell = state does not elect option. “Unknown” = state’s plans undetermined at time of survey. SOURCES: Julie Stone, Medicaid Eligibility for Persons Age 65+ and Individuals with Disabilities: 2009 State Profiles (Cong. Research Serv., June 2011); KFF Medicaid HCBS Program Surveys, FY 2018. |

|||||