Being Low-Income and Uninsured in Missouri: Coverage Challenges during Year One of ACA Implementation

How do the low-income uninsured access care?

The ultimate goal of expanding health insurance coverage is to help people access the medical services that they need. A large body of literature has documented that people with insurance are more likely than those without to be linked to regular care, are less likely to postpone care when they need it, and have an easier time accessing services. As in the past, where we found that low-income adults without coverage in Missouri continue to lag behind their insured counterparts in access to care,1 this year’s survey findings continue to support the literature, indicating that the low-income uninsured are less likely to have a usual source of care than those enrolled in MO HealthNet or the low-income privately insured. The low-income uninsured also use medical care at lower rates, and ultimately go without care more frequently than those enrolled in MO HealthNet or the low-income privately insured.

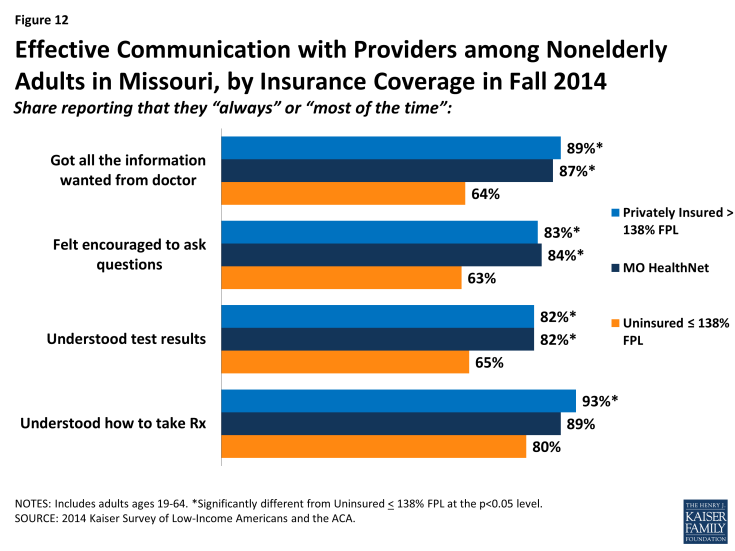

The uninsured are less likely to report being linked to care than those with coverage. The low-income uninsured are less likely than those enrolled in MO HealthNet or those who are low-income and enrolled in private coverage to have usual source of care or a place to go when they are sick or need advice about their health (not counting the emergency room); they were also less likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care (Figure 8). Having a usual source of care or regular doctor is an indicator of being linked to the health care system and having regular access to services. These patterns reinforce a large body of research that finds that having coverage is associated with improved access to care.

Figure 8: Share of Nonelderly Adults in Missouri with a Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

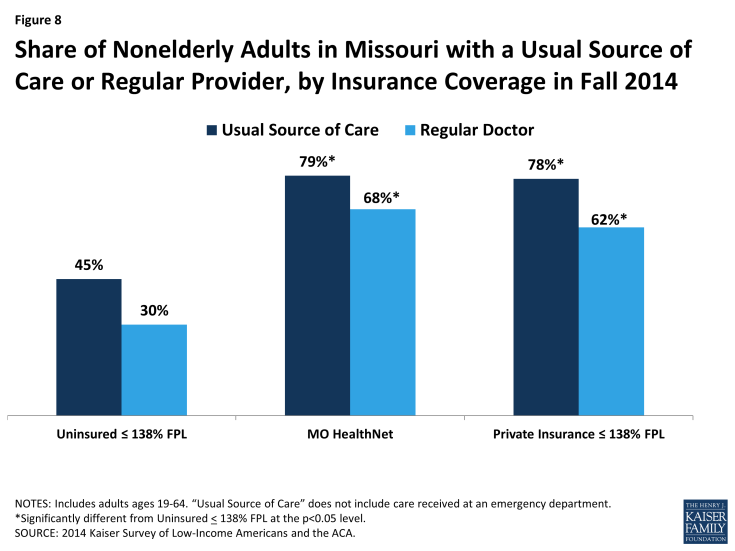

Clinics and health centers remain an important source of care for the low-income uninsured. Among those who have a usual source of care, the low-income uninsured are less likely than the low-income privately insured to say they received care in a physician’s office. Four in ten of the low-income uninsured who have a usual source of care receive care there, as opposed to nearly six in ten (59%) of the low-income privately insured. Over half of those enrolled in MO HealthNet say they receive care in a physician’s office, although this result is not statistically different from the low-income uninsured. While a physician’s office is the most common location for receiving care amongst the low-income uninsured with a usual source of care, it is closely followed by clinics and health centers (38%) (Figure 9). Although low-income adults across the board are most likely to say they chose their usual source of care because their preferred provider is there (Additional Table A2), about a fifth of uninsured low-income adults say they chose their site of care because of affordability. Most clinics and health centers offer care on a reduced fee or sliding scale basis, making them an important source of care for low-income people without insurance.

Figure 9: Type of Place Used for Usual Source of Care among Nonelderly Adults in Missouri, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

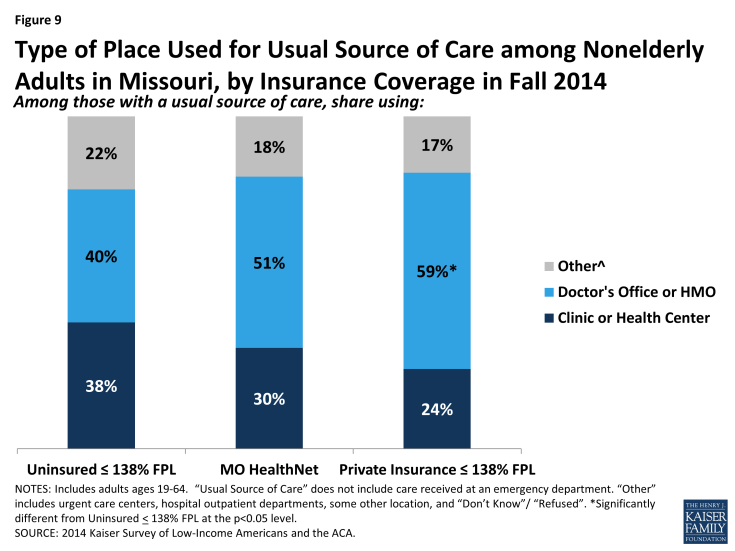

Low-income uninsured adults are less likely than other low-income adults to report using medical services and are more likely to go without needed care. Only fifty-five percent of the low-income uninsured used any medical services compared with over 90 percent (91%) of those enrolled in MO HealthNet and over 70 percent (73%) of the low-income privately insured.2 Only about a quarter of the low-income uninsured had a check-up or other preventive care visit since January 2014, compared 70 percent of those enrolled in MO HealthNet and a little over half (52%) of the low-income privately insured (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Use of Medical Services among Nonelderly Adults in Missouri, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

Over twice as many low-income uninsured postponed or went without care as those who were low-income and privately insured (55% versus 25%), and about four times as many low-income uninsured never got their needed care as the low-income privately insured (41% versus 11%). Although there was no significant difference between the share of low-income uninsured adults and MO HealthNet enrollees who postponed or went without care, nearly twice as many low-income uninsured never got their needed care compared to MO HealthNet enrollees (41% versus 21%) (Figure 11). Postponing care can have major negative implications: about a quarter (26%) of the low-income uninsured postponed care, and consequently lost significant time at work, school, or other important life activities, 28% had their condition worsen, and 42% had their stress level seriously increased. These rates of serious consequences due to postponing care were higher among the uninsured population than among their publicly or privately insured counterparts.

Figure 11: Unmet Need for Care among Nonelderly Adults in Missouri, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

The low-income uninsured were also more likely to go without needed care than the mid-income uninsured. Over half (55%) of the former postponed or went without care, compared with about 40 percent (39%) of the latter (Additional Table A2). This pattern could reflect lower levels of need for health care than those in the low- income range who remained uninsured or could reflect increased ability to meet need due to access to more financial resources.

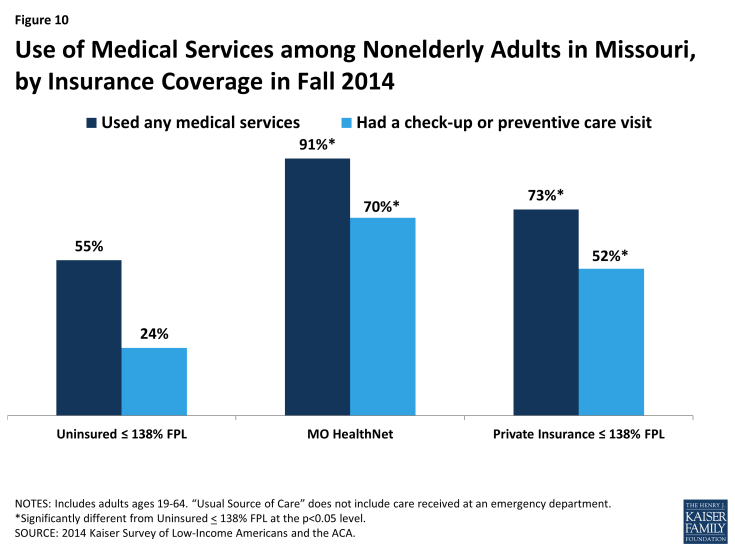

Although overall, a majority of people reported effective communication with their providers, the low-income uninsured experience more difficulty effectively communicating with their providers than do the low-income privately insured and those enrolled in MO HealthNet. Once people get into care, health literacy—or “patients’ ability to obtain, process, and understand the basic health information and services they need to make appropriate health decisions”3—plays an important role in how that care affects health outcomes. Health literacy depends on a range of factors related to patients (e.g., engagement in care), providers (e.g., how the information is communicated), service setting (e.g., the length of time of the interaction), and the nature of the visit (e.g., the complexity of health information). About six in ten (64%) of the low-income uninsured got all the information they wanted from their doctor or nurse, about six in ten (63%) felt encouraged to ask health questions, and about two thirds (65%) understood test results all or most of the time. However, these are lower rates compared to those enrolled in MO HealthNet and the low-income privately insured: nearly 90 percent of those enrolled in MO HealthNet and of the low-income privately insured got all the information they wanted from their provider, over 80 percent of each felt encouraged to ask questions, and about 80 percent of each understood their test results all or most of the time (Figure 12). While it’s not clear based on survey findings why these differences exist, it is possible that they are linked to uninsured adults’ lower likelihood of having a regular provider with whom they have an established rapport.