Policy Options to Sustain Medicare for the Future

Published:

Introduction

Preface and Introduction

.

Preface

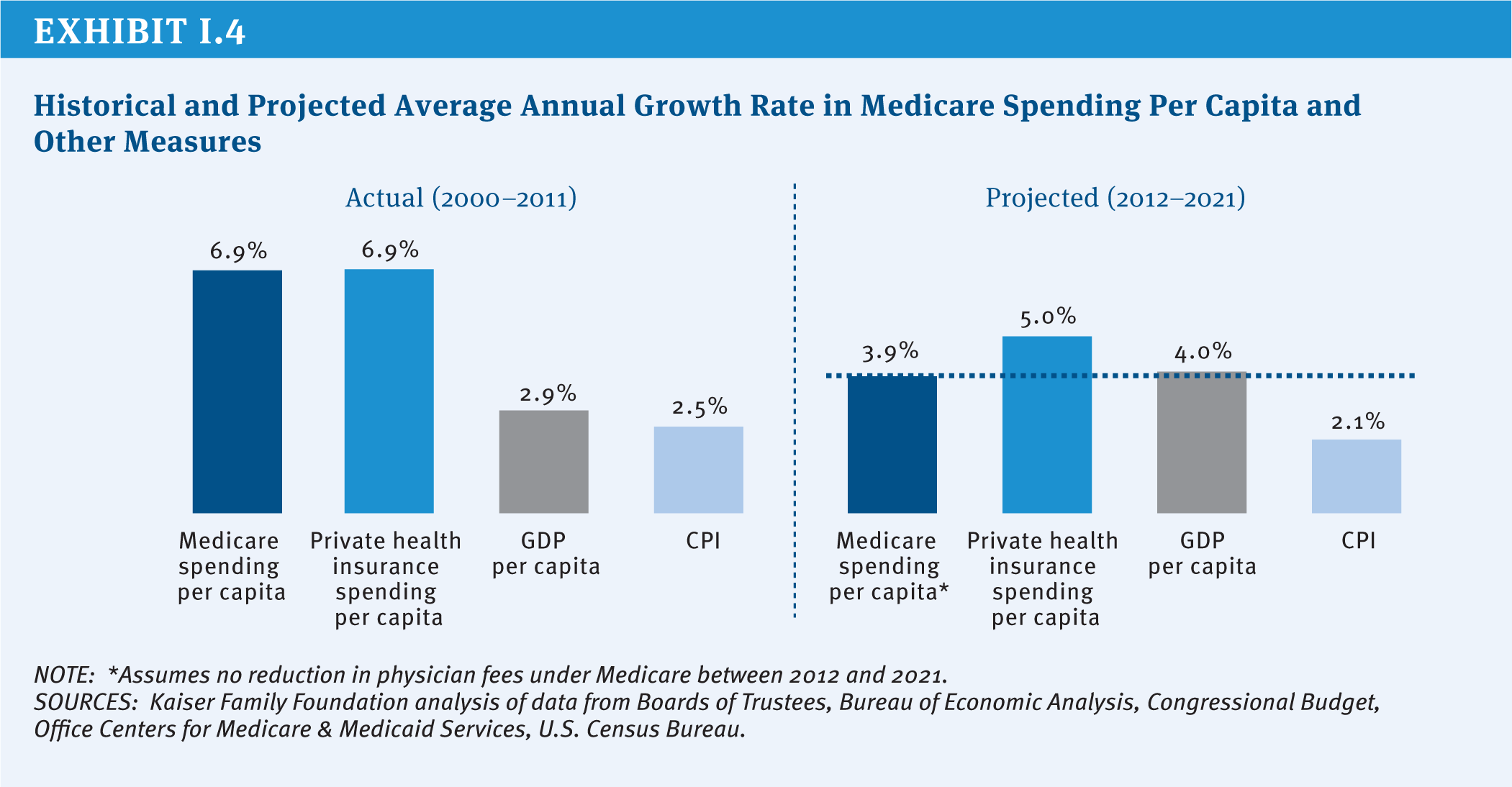

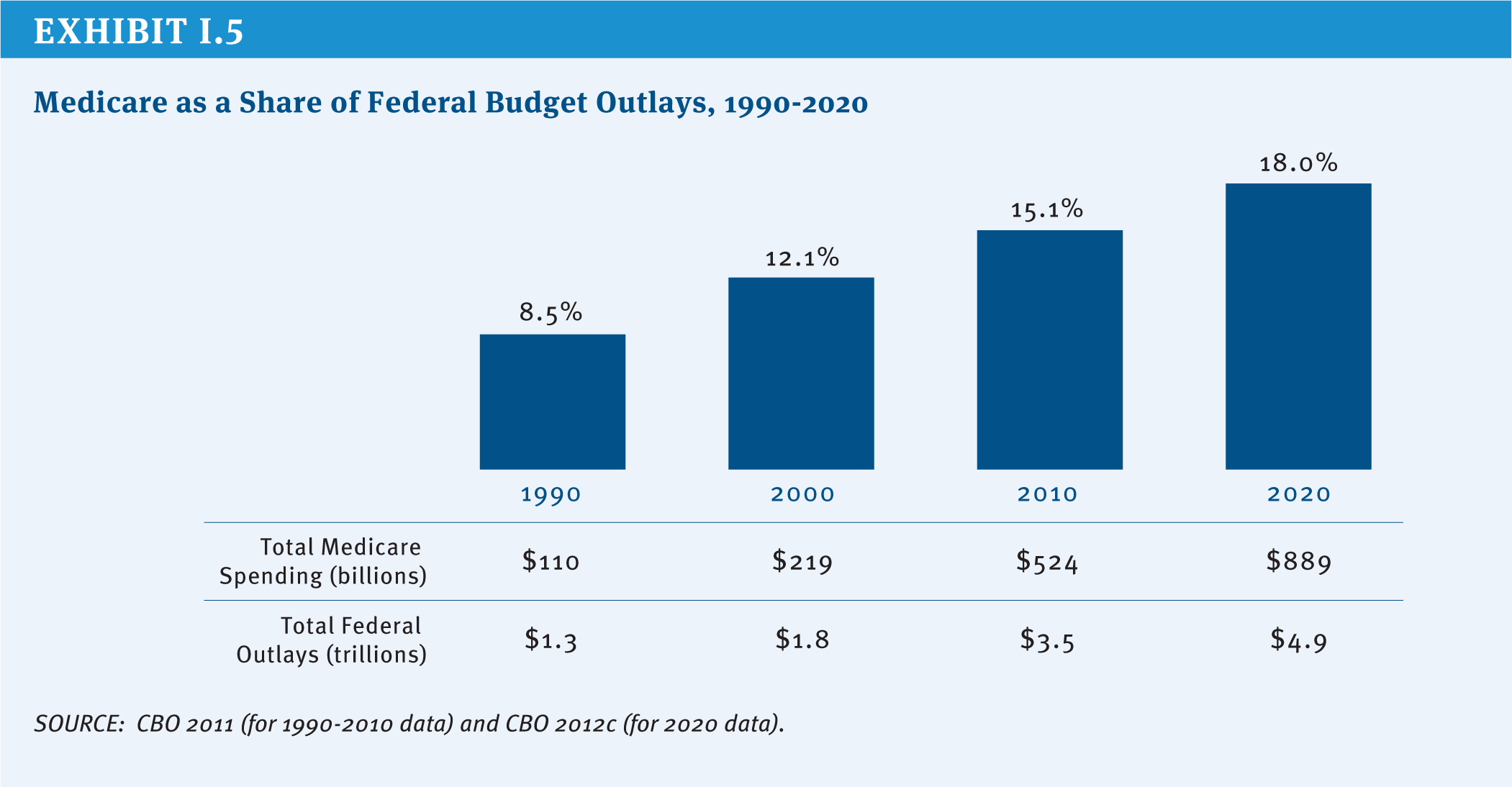

Policymakers are engaged in an historic effort to stimulate economic growth and reduce the Federal budget deficit and debt. Medicare, the nation’s health insurance program for adults ages 65 and over and non-elderly people with permanent disabilities, is a key part of these discussions, principally because the program accounts for 15 percent of the Federal budget and program spending is rising as a share of the budget and the nation’s gross domestic product. President Obama, Congressional leaders in both parties, and other policymakers and stakeholders have proposed changes to Medicare as part of comprehensive approaches to deficit reduction. Important differences are reflected in the various proposals in terms of the magnitude and scope of proposed changes and how program savings would be achieved. Over the next decade, Medicare is projected to grow more slowly than private health care spending on a per capita basis, but the retirement of the Baby Boom generation and rising health care costs pose fiscal challenges for the nation. How these challenges are addressed has important implications for the Federal budget, the nation’s health care system, health care providers, taxpayers, and people with Medicare.

To inform ongoing and future policy discussions, this report presents a compendium of policy ideas that have the potential to produce Medicare savings. The report discusses a wide range of options and lays out the possible implications of these options for Medicare beneficiaries, health care providers, and others, as well as estimates of potential savings, when available. Of note, this report does not attempt—nor is it intended—to endorse or recommend a specific set of Medicare program changes or reach a specific target for savings. The report also does not include options that would be likely to require additional Federal spending, such as improving benefits or strengthening financial protections for beneficiaries with low incomes. And while it is clear that health care costs in the public and private sector are interrelated and that changes in each sector directly affect spending in the other, the report does not include options to address health care costs more broadly, including public health improvement efforts that would undoubtedly affect Medicare spending, such as reducing obesity.

There are many potential pathways and policy options that could be considered to sustain Medicare for the future. For example, one approach would leave the current program structure largely intact but make modifications to features of it, for example, by adjusting existing payment rules for providers and plans or raising beneficiary cost-sharing requirements for specific services. Another approach would attempt to leverage Medicare’s significant role in the health care marketplace to create stronger incentives to promote value over volume, for example, by accelerating the implementation of delivery system reforms, promoting models of care that improve the management of care for high-cost, high-need beneficiaries, and introducing new mechanisms to constrain excess payments and utilization. And yet another approach would change the fundamental structure of Medicare from a defined benefit program to one that instead provides an entitlement to a government contribution for the purchase of coverage. Each of these pathways could accommodate some specific savings and revenue options for Medicare that have been discussed, including raising the age of eligibility, increasing the payroll tax or raising other revenues, and capping annual program spending.

To produce this report, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation spent several months in 2012 consulting some of the nation’s top experts in Medicare and health care policy, including individuals with a wide variety of perspectives who have served in senior positions on Capitol Hill and in the Executive Branch, academia, and the health care industry. We asked for their input on defining the problem, as well as their suggestions for options, pathways, and priorities.

These experts were very generous with their thoughts, ideas, and time, for which we are extremely thankful. A list of these experts and their affiliations at the time of the interview on page iii, with the exception of a few people who requested that they not be listed. The inclusion or exclusion of specific policy options and the related discussion in this report cannot and should not be attributed to any of these experts individually or collectively.

We also conducted an extensive review of existing literature to identify potential options to sustain Medicare for the future. The report includes many options described or endorsed by the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (the Simpson-Bowles commission), the Bipartisan Policy Center Task Force on Deficit Reduction, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and many others. We also worked with a team of seasoned policy experts who fleshed out these concepts and ideas for inclusion in this report to present a thorough explanation of the context, impacts, and, when available, potential savings. In particular, we would like to acknowledge Robert Berenson for making significant contributions to several parts of this report, and Leslie Aronovitz, Randall Brown, Judy Feder, Jessie Gruman, Jack Hoadley, Andy Schneider, and Shoshanna Sofaer for their contributions to specific topic areas. We also would like to acknowledge Chad Boult, Susan Bartlett Foote, Richard Frank, Joanne Lynn, Robert Mechanic, Diane Meier, Peter Neumann, Joseph Ouslander, Earl Steinberg, George Taler, and Sean Tunis for their participation in small-group discussions related to specific topics covered in this report, and Actuarial Research Corporation (ARC) for providing cost estimates and distributional analysis of several options. Technical support in the preparation of this report was provided by Health Policy Alternatives, Inc. We are indebted to Richard Sorian for bringing to this project his keen policy insight and skillful editorial assistance.

This report would not have been written were it not for a few exceptionally talented and dedicated staff of the Kaiser Family Foundation. In particular, Zachary Levinson worked tirelessly and enthusiastically on nearly every aspect of this project, and Rachel Duguay helped get the project up and running. Gretchen Jacobson was instrumental in developing several areas of the report, and Jennifer Huang lent her creative talents to the exhibits and production process. We also would like to thank Carene Clark, Anne Jankiewicz, and Evonne Young for their work on the report design and layout. Lastly, we would like to acknowledge The Atlantic Philanthropies for financial support for this project.

We hope this report provides valuable information in ongoing efforts to sustain Medicare for the future.

Sincerely,

Patricia Neuman, Sc.D

Senior Vice President

Director, Program on Medicare Policy

Director, Kaiser Project on Medicare’s Future

Kaiser Family Foundation

Juliette Cubanski, Ph.D.

Associate Director

Program on Medicare Policy

Kaiser Family Foundation

.

Experts Interviewed for this Project

Joseph Antos

American Enterprise Institute

Scott Armstrong

Group Health Cooperative

Katherine Baicker

Harvard University

Donald Berwick

Center for American Progress

Jonathan Blum

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

David Blumenthal

Partners HealthCare

Sheila Burke

Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz, PC

Christine Cassel

American Board of Internal Medicine

Michael Chernew

Harvard University

David Cutler

Harvard University

Duane Davis

Geisinger Insurance Operations

Karen Davis

The Commonwealth Fund

Ezekiel Emanuel

University of Pennsylvania

Judith Feder

Georgetown University

Elliot Fisher

Dartmouth College

Patricia Gabow

Denver Health and Hospital Authority

Richard Gilfillan

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation

Sherry Glied

Columbia University

Thomas Graf

Geisinger Health System

Jonathan Gruber

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Karen Ignagni

America’s Health Insurance Plans

Mark McClellan

The Brookings Institution

Marilyn Moon

American Institutes for Research

Joseph Newhouse

Harvard University

Len Nichols

George Mason University

Robert Reischauer

The Urban Institute

John Rother

National Coalition on Health Care

John Rowe

Columbia University

Earl Steinberg

Geisinger Health System

Glenn Steele

Geisinger Health System

Simon Stevens

UnitedHealth Group

Janet Tomcavage

Geisinger Health Plan

Bruce Vladeck

Nexera, Inc.

Gail Wilensky

Project HOPE

.

Introduction

Medicare’s History of Coverage and Care for Seniors and People with Disabilities

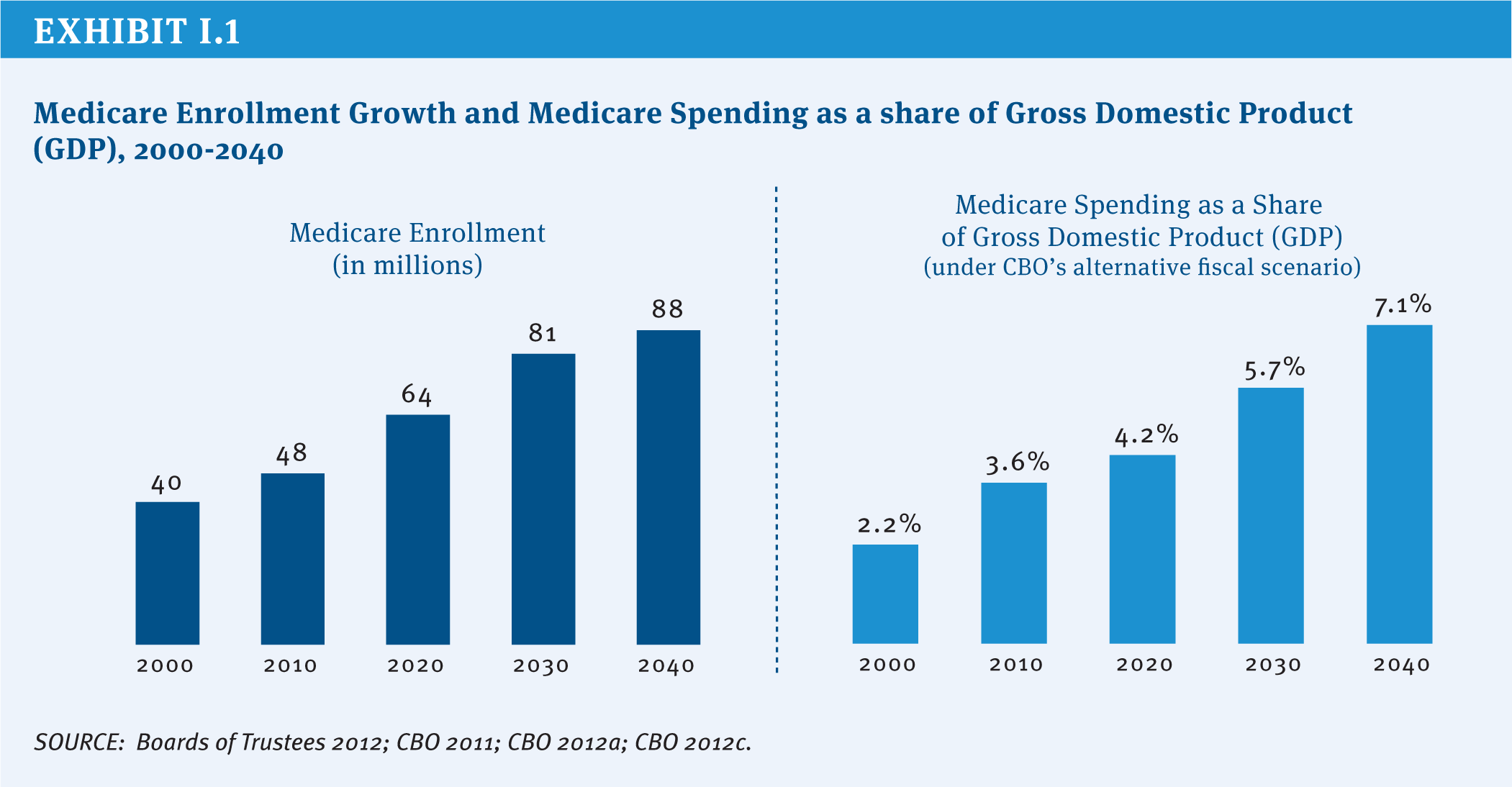

Medicare was signed into law July 30, 1965, and went into effect one year later. Since then, Medicare has provided health insurance coverage for more than 130 million Americans, including adults ages 65 and over and younger people living with permanent disabilities (HHS 2012). Medicare is a Federal entitlement program that provides a guaranteed set of benefits to all Americans who meet the basic eligibility requirements, without regard to medical history, income, or assets. In 2012, Medicare provided health insurance coverage to 50 million people. With total Medicare expenditures estimated to rise as a share of the Federal budget and the nation’s economy, Medicare is once again at the forefront of policy discussions (Exhibit I.1).

Medicare has made a significant contribution to the lives of older Americans and people with disabilities by bolstering their economic and health security and helping to lift millions of older Americans out of poverty. Prior to Medicare, more than half of all Americans over age 65 were uninsured (De Lew 2000), and nearly a third of seniors were in poverty; today virtually all seniors have Medicare coverage and the official poverty rate among those ages 65 and older is just under 9 percent (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2012). For younger people living with disabilities, Medicare has provided life-saving and life-sustaining access to care and treatment that would otherwise be out of reach for many and has allowed millions to stay in their homes rather than be institutionalized.

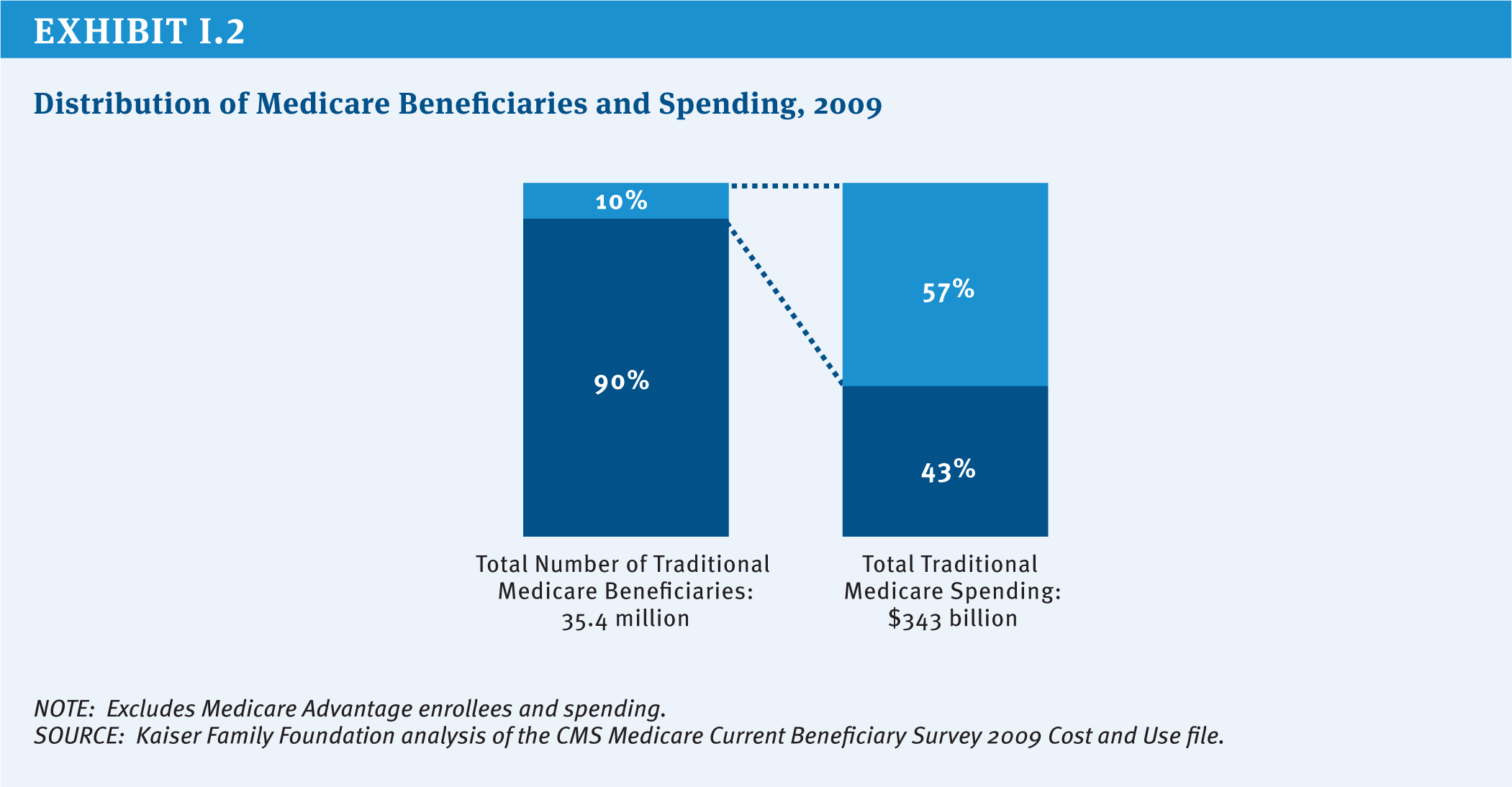

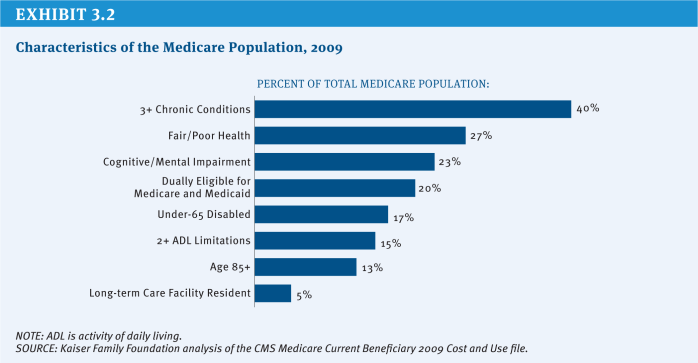

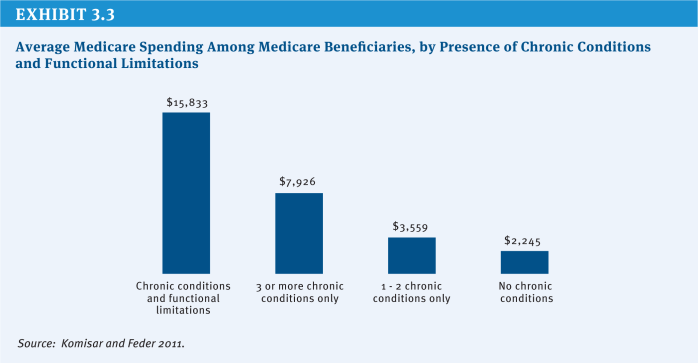

Health insurance coverage is important to people of all ages, but especially important for seniors and adults with disabilities who are significantly more likely than others to need costly medical care. Medicare pays for health care services, including, but not limited to, hospitalizations, physician services, medical devices, and prescription drugs. Each year, more than three-quarters of people with Medicare have at least one physician office visit; more than one in four go to an emergency department one or more times; nearly one in five beneficiaries are admitted to a hospital; and nearly one in 10 have at least one home health visit. In 2013, average per capita Medicare spending is projected to exceed $12,000 (Boards of Trustees 2012). While most people with Medicare use some amount of medical care in any given year, a majority of spending is concentrated among a relatively small share of beneficiaries with significant needs and medical expenses (Exhibit I.2).

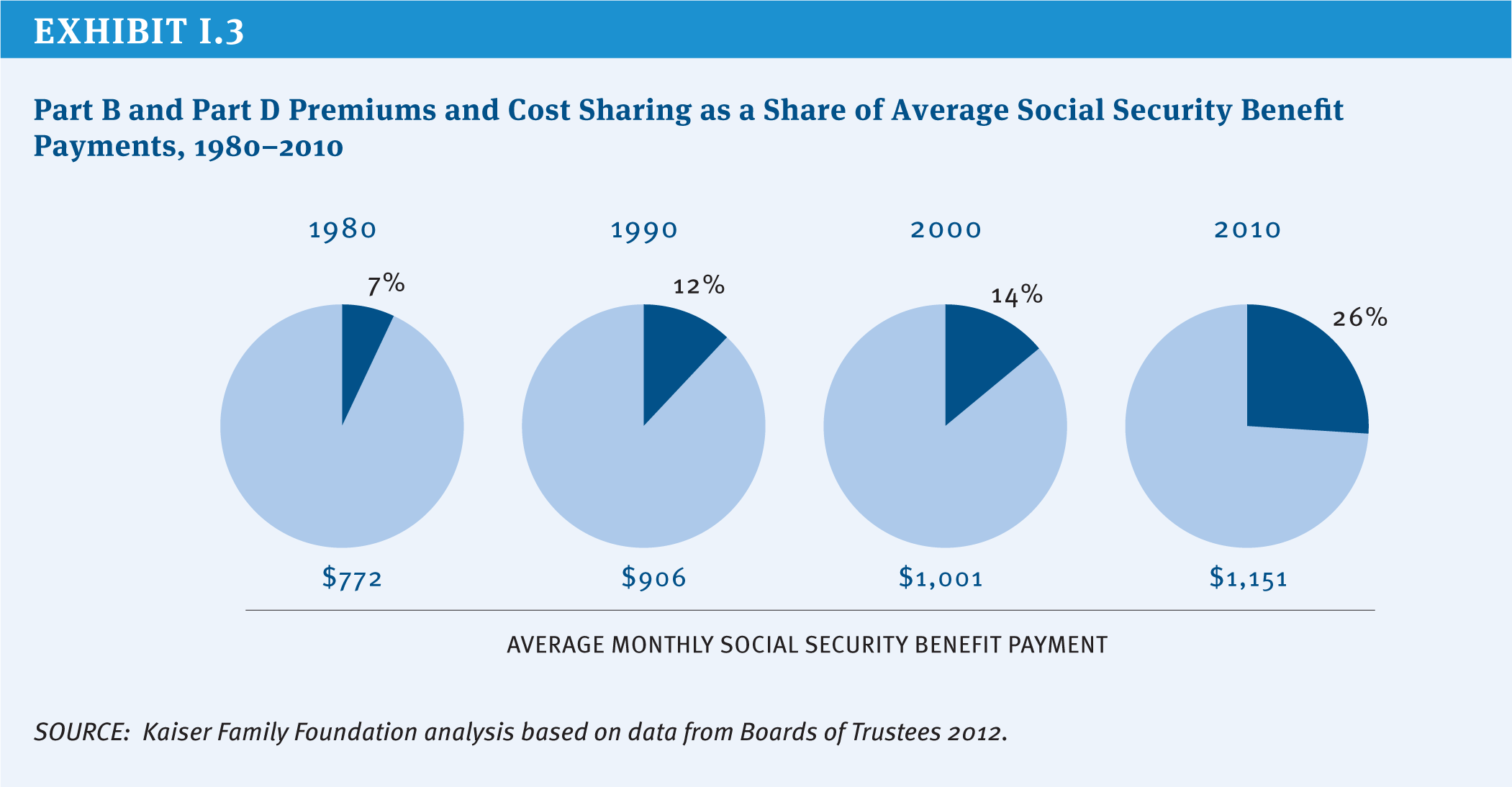

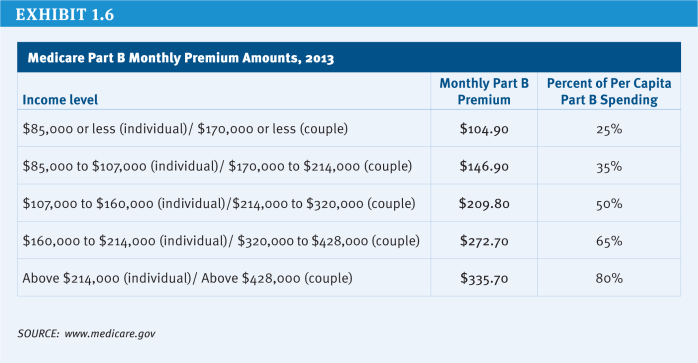

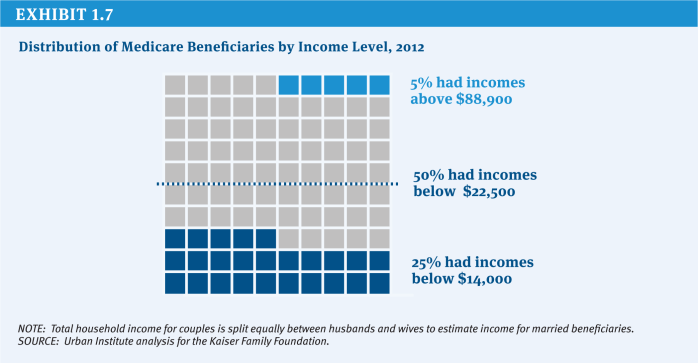

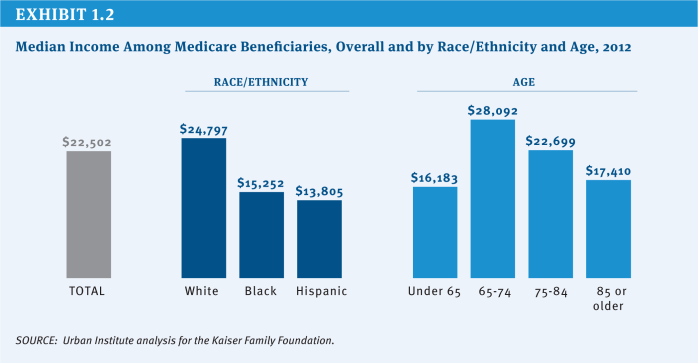

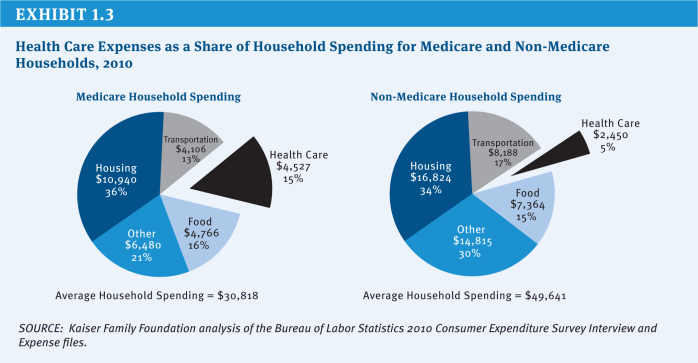

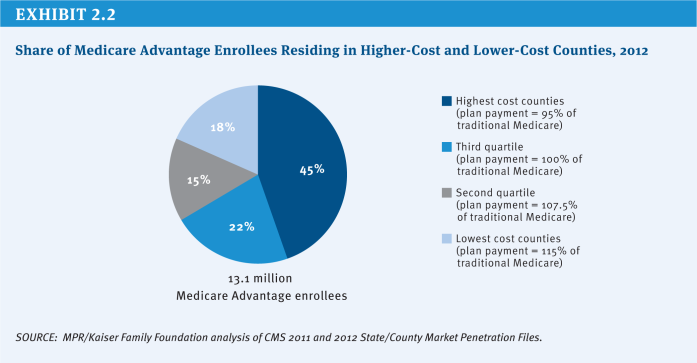

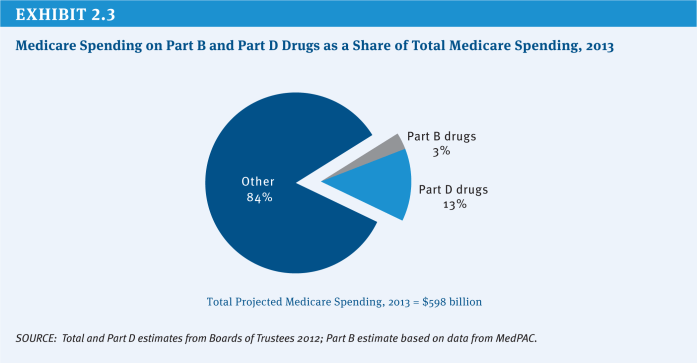

Despite the important role that Medicare plays in providing health and economic security for beneficiaries of the program, it does not cover all the costs of health care. Medicare cost sharing is relatively high and, unlike most private health insurance policies, Medicare does not place an annual limit on the costs that people with Medicare pay out of their own pockets. Many Medicare beneficiaries have supplemental coverage to help pay for these costs, but with half of beneficiaries having an annual income of $22,500 or less in 2012, out-of-pocket spending represents a considerable financial burden for many people with Medicare. Cost sharing and premiums for Part B and Part D have consumed a larger share of average Social Security benefits over time, rising from 7 percent of the average monthly benefit in 1980 to 26 percent in 2010 (Exhibit I.3). Medicare beneficiaries spend roughly 15 percent of their household budgets on health expenses, including premiums, three times the share that younger households spend on health care costs. Finally, Medicare does not cover costly services that seniors and people with disabilities are likely to need, most notably, long-term services and supports and dental services.

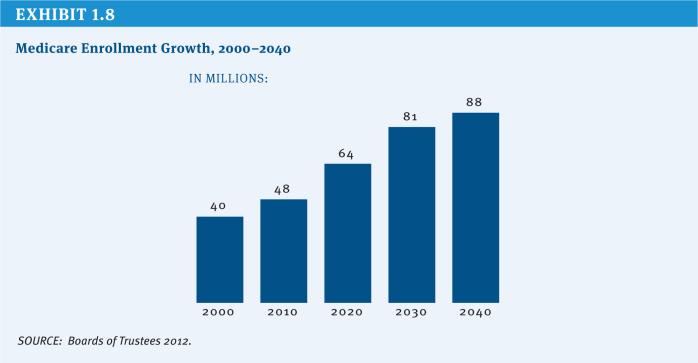

Medicare’s Future Challenges

Persistently high rates of growth in health care spending combined with demographic trends pose a serious challenge to the financing of Medicare in the 21st century. The number of people eligible for Medicare is projected to rise sharply from 50 million today to nearly 90 million by 2040, with a particularly high rate of growth in enrollment between now and 2030 (Exhibit I.1). According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the aging of the population is expected to account for 60 percent of the growth in Federal health spending over the next 25 years, while “excess cost growth”1 accounts for 40 percent (CBO 2012a). As such, the long-run fate of Medicare depends on solving the larger problem of rising health care costs, which pose a similar challenge to all payers, including employers, individuals, and other government programs.

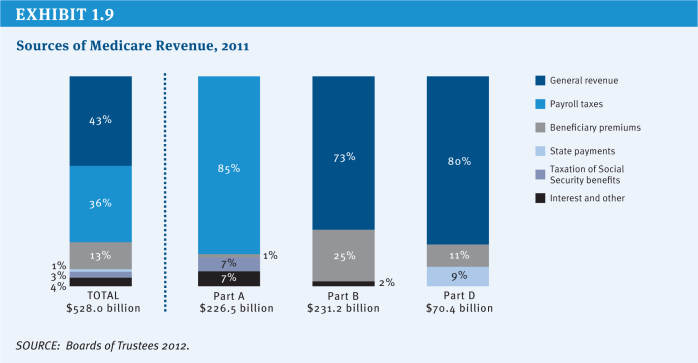

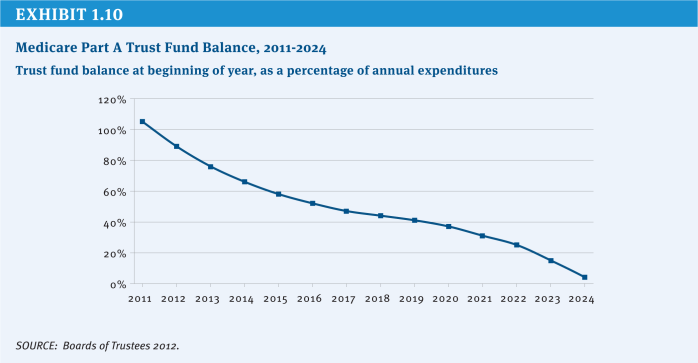

The aging of the Baby Boom generation not only makes millions of Americans newly eligible for Medicare, it also reduces the number of workers paying the Medicare payroll tax, a primary source of revenue for the Medicare Part A Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund. The HI trust fund currently is projected to be solvent through 2024, but will have insufficient funds to pay full benefits beyond that point (Boards of Trustees 2012). In the past, Congress has taken steps to maintain and extend the solvency of the HI trust fund by restraining growth in Medicare spending and increasing payroll tax revenue, and will need to take action to extend the life of the trust fund at some point in the future to fully fund current benefits.

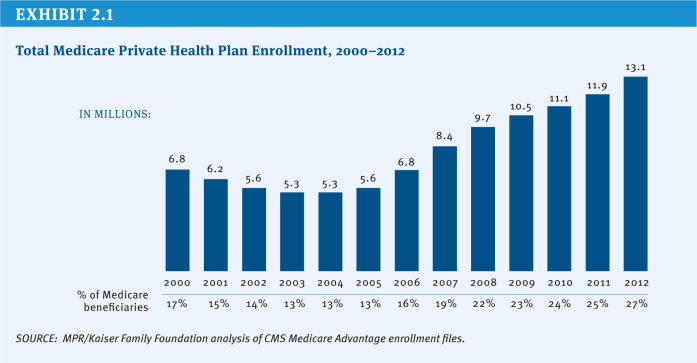

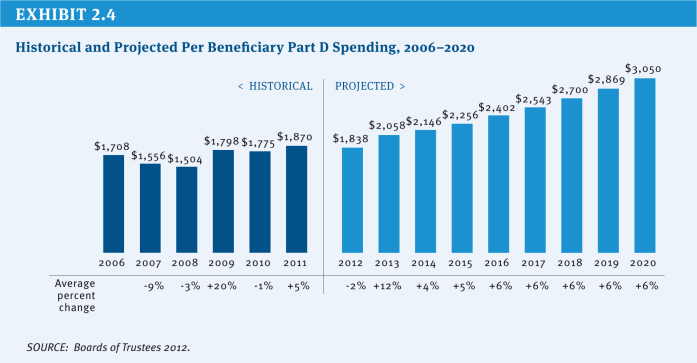

Over the course of the past five decades, Congress has made changes to Medicare on numerous occasions to address emergent issues, benefit gaps, financing challenges, spending growth, and policy priorities (See Textbox “Major Amendments to Medicare” beginning on page xi). For example, Medicare’s benefit package has been updated to include hospice benefits, outpatient prescription drugs, and more comprehensive coverage of preventive services. Medicare also has expanded the role of private entities, not only the contractors that help administer the program and process claims, but also the private health plans that provide benefits under Medicare Advantage and Part D (prescription drug coverage). Medicare payment systems have evolved over time, shifting from cost-based fee-for-service reimbursement systems to prospective and bundled payments to providers, a shift that has helped to constrain the growth in program spending.

The most recent sweeping changes to Medicare were enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010. While the ACA retained Medicare’s structure as an entitlement to a set of defined benefits, the law contains several provisions designed to reduce provider payment growth, increase revenues, improve certain benefits, reduce fraud and abuse, and invest in research and development to identify alternative provider payment mechanisms, health care delivery system reforms, and other changes intended to improve the quality of health care and reduce Medicare spending. According to CBO, these changes reduced projected Medicare spending by $716 billion over 10 years (2013–2022) (Elmendorf 2012).

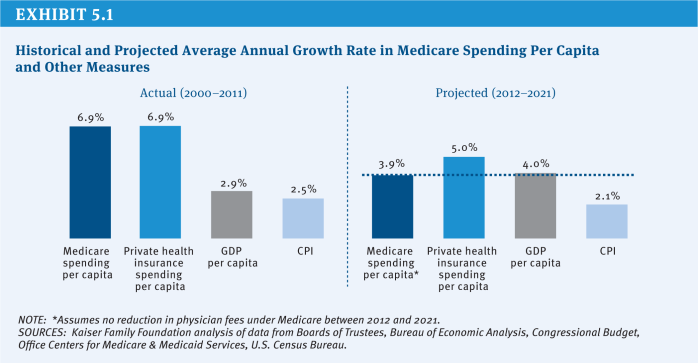

Partly as a result of payment changes enacted in the ACA, Medicare per capita spending is now projected to grow by 3.9 percent annually between 2012 and 2021, compared with 5.0 percent average annual per capita growth projected for private health insurance spending2 (Exhibit I.4). Even with the relatively low Medicare per capita growth rate projected for the next decade, policymakers face an ongoing challenge in finding ways to reduce long-term spending growth and continue to finance care for an aging population. And with Medicare spending accounting for a growing share of the Federal budget and the gross domestic product (GDP), Medicare’s challenges will be inextricably linked to ongoing deliberations over how to reduce annual Federal deficits and the national debt (Exhibit I.5).

Looking to the future, Medicare faces a number of challenges, including:

» A mismatch between projected revenues and spending that is projected to result in insufficient funds to support services that are paid for by the Hospital Insurance trust fund beginning in 2024;

» An outdated benefit design, with relatively high deductibles and cost-sharing requirements, no limit on out-of-pocket spending, and benefit gaps, that encourages beneficiaries to seek supplemental insurance and contributes to relatively high out-of-pocket spending;

» Several provider payment systems that reward volume, rather than value or patient outcomes, without adequate incentives to encourage providers to coordinate and manage patient care, particularly for high-need, high-cost beneficiaries;

» A physician payment formula, known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), that aims to constrain the growth in expenditures associated with physician services, but has led to frequent Congressional intervention to avoid sudden and severe reductions in doctors’ fees; and

» An ongoing struggle to constrain the growth in health care spending, while providing fair payments to providers and plans and high-quality, affordable medical care for beneficiaries.

Given these challenges, the debate about Medicare’s future is likely to revolve around several key questions:

- How much can Medicare absorb in additional savings, and over what period of time, without negatively affecting patient care?

- How should efforts to sustain Medicare be distributed among providers, plans, beneficiaries, and taxpayers?

- What are the most promising strategies for reducing inefficiencies and promoting high-quality care: accelerated delivery system reforms; greater competition among plans and providers; value-based purchasing strategies; stronger financial incentives to encourage care management?

- Should Medicare’s basic entitlement be changed from a program that guarantees a defined set of benefits to one that provides a defined contribution for the purchase of insurance?

- Should reform efforts focus specifically on Medicare or be broadened to address the growth in health care spending across all payers?

Since the enactment of Medicare, policymakers have been challenged to balance the interests of Medicare beneficiaries, taxpayers, health care providers, health plans, and manufacturers. Today’s national economic and fiscal constraints make this task more difficult than ever. The nature of the options presented in this report underscores the scale of changes that may be in store for Medicare in the future, and the potential effects of these changes on beneficiaries and providers of care mean that debating them will be contentious. Notwithstanding the difficult choices that lie ahead in coming to consensus on Medicare program changes, the effort to sustain Medicare for the future is a vital endeavor.

Report Outline

This report presents a compendium of policy ideas that have the potential to produce Medicare savings or generate revenue, while also laying out the possible implications of these options for beneficiaries, health care providers, and others, as well as estimates of potential savings, when available. This report does not attempt—nor is it intended—to endorse or recommend a specific set of Medicare policy options or reach a specific target for savings.

The report is divided into five sections, each of which presents options within several main topic areas. Topic areas are cross-referenced where options and ideas overlap. The five sections describe options related to:

» Medicare eligibility, beneficiary costs, and program financing;

» Medicare payments to providers and plans;

» Delivery system reform and options that focus on Medicare beneficiaries with high needs;

» The basic structure of the Medicare program; and

» Medicare program administration and governance, including program integrity.

We generally rely on cost estimates from official and publicly available government sources, including CBO, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG), MedPAC, and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). For many options, no cost estimate is available from one of these sources. In a few cases, estimates from other sources are presented and noted accordingly. For a complete list of options included in this report and budget effects, see Appendix p. 197, Table of Medicare Options and Budget Effects.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. 2012. 2012 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, April 23, 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2011. The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2011 to 2021, January 2011.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012a. The 2012 Long-Term Budget Outlook, June 4, 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012b. Monthly Budget Review, Fiscal Year 2012, October 5, 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012c. An Update to The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022, August 2012.

Nancy De Lew. 2000. “Medicare: 35 Years of Service,” Health Care Financing Review, 2000.

Douglas W. Elmendorf. 2012. Letter to the Honorable John Boehner, Speaker of the House, July 24, 2012.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2012. Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, Historical Poverty Tables, Table 3. Poverty Status of People, by Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1959 to 2011, 2012.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2012. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, unpublished estimate, 2012.

Major Amendments to Medicare

Since it was enacted in 1965, Medicare frequently has been amended in legislation to either add benefits, control costs, or both. Some of the major revisions include:

1972

Under the Social Security Amendments of 1972, Medicare eligibility is expanded to include people under age 65 with long-term disabilities (who received Social Security Disability Insurance payments for 24 months) and individuals suffering from end stage renal disease (ESRD) who require maintenance dialysis or a kidney transplant. The law also authorizes Medicare to contract with health maintenance organizations (HMOs), through either cost reimbursement or risk contracts.

1980

The Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1980 eliminates the prior hospitalization requirement for home health services, removes the 100 home health visit limitations under Part A and Part B, and requires all home health visits to be paid by Part A unless the beneficiary is only enrolled in Part B.

1982

Medicare is expanded to include a new hospice benefit under the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982. Part B premiums are set to cover 25 percent of program costs, Federal employees are required to pay the Medicare payroll tax, and HMOs are now paid based on 95 percent of the adjusted average per capita cost (AAPCC) of caring for beneficiaries under fee-for-service Medicare.

1983

As part of the Social Security Amendments of 1983, Medicare adopts a new a prospective payment system (PPS) for inpatient hospital services that pays a predetermined amount for each discharge depending on the patient’s condition. Separate rates are set for diagnosis related groups (DRGs).

1985

The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 establishes the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), requiring hospitals in the U.S. to stabilize patients before transferring them to other facilities. COBRA also makes the Medicare hospice benefit permanent.

1987

In response to concerns raised about the quality of care in nursing homes, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 sets new quality standards for Medicare and Medicaid certified nursing facilities while also modifying provider payments to reduce growth. Also that year, the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Reaffirmation Act of 1987 freezes Medicare payment rates in an attempt to slow Medicare spending.

1988

Congress adopts, and, in 1989, repeals key provisions of the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act that would have capped beneficiaries’ out of pocket costs and added an outpatient prescription drug benefit to Medicare financed through premiums paid by beneficiaries including means-tested payments by upper-income seniors. Provisions expanding financial protections for low-income beneficiaries in Medicare and Medicaid remain in place, however.

1989

Under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989, Medicare physician payments begin to be determined based on a resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) based on the amount of work required to perform a service, replacing a system in which physicians were paid based on their own charges. A new “volume performance standard” is created to guard against sharp increases in the number of services provided to beneficiaries.

1990

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 sets new standards for Medigap policies, including standard benefit designs to facilitate comparisons across plans, curtails the use of preexisting condition limitations and requires new medical loss ratio requirements. Medicare benefits are expanded to include mammography screening.

1993

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 includes reductions in payments to providers as part of deficit reduction legislation. Congress also eliminates the cap on earnings subject to the Medicare payroll tax.

1997

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 makes significant changes to Medicare resulting in savings by tightening Medicare payments to providers, increasing beneficiary premiums, and other provisions. The law establishes prospective fee schedules for all part B services except hospital outpatient services and expands the types of private plans participating in a newly named Medicare+Choice program. The law replaces Medicare’s volume performance standard (VPS) with a new formula—known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR)—designed to guard against volume increases.

2000

The Benefits Improvement and Protection Act (BIPA) expands coverage of preventive care and increases Medicare payments to plans and certain providers. The law modifies payments to Medicare+Choice plans, increasing payments in certain rural and urban counties. It also provides Medicare coverage for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by waiving the 24-month waiting period.

2003

The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) adds a voluntary outpatient prescription drug program to be administered by stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plans (MA-PDs) financing by general revenues, beneficiary premiums, and a “clawback” of savings from the States. MMA also increases Part B premiums for higher income beneficiaries and raises payments to private health plans participating in what is now called “Medicare Advantage.”

2008

The Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA) expands protection of low-income beneficiaries, adds more coverage of preventive care (including a “Welcome to Medicare” physical), and reduces the growth in payments to and imposes new restrictions and requirements on Medicare Advantage plans.

2010

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) reduces the growth in Medicare spending for Medicare Advantage plans, hospitals, and other health care providers; sets a limit on the growth in spending to be enforced through the Independent Payment Advisory Board; improves benefits by gradually closing the Part D coverage gap; expands coverage of preventive services; creates a new Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation to test and implement payment and delivery system reforms to curb costs and improve quality; increases Part B and D premiums for higher-income beneficiaries; raises the Medicare payroll tax on earnings of high-income workers; and establishes fees on manufacturers of branded prescription drugs and medical devices.

2011

The Budget Control Act of 2011 provides for reductions in Medicare spending in the event Congress cannot agree on a long-term deficit and debt reduction plan. Beginning in 2013, Medicare spending will be subject to automatic, across-the-board reductions, known as “sequestration,” that would reduce Medicare payments to plans and providers by up to 2 percent.

2013

The American Taxpayer Relief Act includes provisions to avert a reduction in Medicare physician fees for one year and extends provisions that would have expired under current law and offsets the cost by reducing payments to hospitals and Medicare Advantage plans. The law delays the sequestration of Federal payments to Medicare plans and providers for two months, repeals the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) program authorized under the ACA, and establishes a new Commission on Long-Term Care.

Report

Section 1: Medicare Eligibility, Beneficiary Costs, and Program Financing

.

Age of Eligibility

Options Reviewed

This section reviews two options for raising the age of Medicare eligibility:

» Raise the age of Medicare eligibility from 65 to 67, using a similar phase-in schedule for the Social Security full retirement age

» Raise the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67 only for people with relatively high lifetime earnings

Currently, most Americans become eligible for Medicare benefits when they reach age 65. Raising the age at which people can begin to be covered by Medicare has been proposed as a way of decreasing future Medicare program spending by reducing the number of people on Medicare. Most proposals recommend gradually raising the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67, aligning Medicare eligibility with the full retirement age for Social Security. If adopted in conjunction with coverage expansions included in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Federal savings associated with this change would be partially offset by costs associated with providing subsidies to 65- and 66-year-olds covered in the health insurance exchanges or under Medicaid; the effects for individuals would be expected to vary based on age, income, and source of health insurance coverage.

Background

Since Medicare was enacted in 1965, eligibility has generally been based on age (65 and older), employment history (individuals or their spouses contribute Medicare payroll taxes for at least 10 years), and citizenship/residency status.1 The eligibility age for both Medicare and full retirement benefits through Social Security were aligned until 2000, when, as a result of a 1983 law, the normal retirement age for Social Security began to rise in stages from age 65 to age 67.

In the past, a major concern related to raising the Medicare eligibility age has been the potential impact on people ages 65 and 66 who could become uninsured as a result of losing access to Medicare. Studies conducted prior to enactment of the ACA estimated that the number of uninsured 65- and 66-year-old adults would increase if the Medicare eligibility age were raised, in the absence of reforms that would provide older adults with access to affordable insurance, without pre-existing conditions exclusions and other restrictions (Davidoff and Johnson 2008). These studies documented that people who were not entitled to Medicare benefits at age 65 would have limited access to private insurance coverage unless they were working and had access to employer-sponsored group coverage. Such concerns were a major deterrent to increasing the Medicare eligibility age prior to enactment of the ACA.

With the implementation of the ACA, including coverage expansions and Federal subsidies for private coverage through the health insurance exchanges and expanded coverage for low-income individuals under Medicaid, the law will change the insurance coverage landscape for nonelderly individuals beginning in 2014. Combined with an individual mandate, the prohibition against insurers excluding people from coverage due to pre-existing conditions and limits on age-related rating bands, these reforms could create an avenue for affordable health insurance coverage for 65- and 66-year-olds if the Medicare eligibility age were raised above age 65. The individual mandate applies to all individuals, with certain exceptions unrelated to age. If the Medicare eligibility age is increased to 67, 65- and 66-year-olds would be eligible for income-based subsidies as long as they do not have an offer of coverage from an employer. However, a statutory change would be needed to extend eligibility for the Medicaid expansion to 65- and 66-year-olds because the ACA specifically limits the expansion to individuals who meet the new income requirements and are under age 65.

Policy Options

OPTION 1.1

Raise the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67

Under this option, the age of Medicare eligibility would gradually increase from 65 to 67, aligning Medicare with the full retirement age for Social Security, whereby the eligibility age is increasing by two months per year, reaching 67 in 2027 for people born in 1960 or later. This option could be modified by: (1) modifying the implementation date; (2) varying the number of years over which the age of eligibility would be raised; (3) indexing the age of eligibility to life expectancy in order to provide greater Federal savings and account for continued gains in life expectancy. The discussion below does not address the effects of these modifications.

Budget effects

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that raising the Medicare eligibility age gradually to 67, by two months per year beginning in 2014, would reduce net Federal spending by $113 billion over 10 years (2012–2021) (CBO 2012). This takes into account new Federal costs associated with health insurance exchange subsidies and the Medicaid expansion, and the loss of Medicare Part B premium revenues.

Discussion

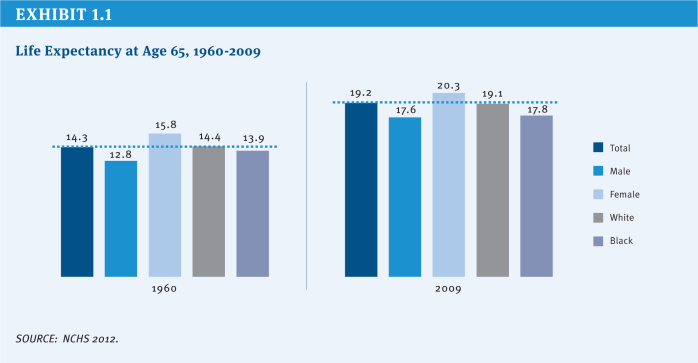

Proponents cite both demographic and economic justifications for increasing the Medicare eligibility age to achieve Medicare savings. Aligning the Medicare age of eligibility with the age when people can claim full retirement benefits for Social Security is bolstered by demographic trends, in particular, gains in average life expectancy at age 65. In 1960, just prior to the enactment of Medicare, the average 65-year-old could expect to live another 14.3 years; five decades later, the average life expectancy for a 65-year-old has increased to 19.2 years (NCHS 2012) (Exhibit 1.1). Gains in life expectancy result in an increase in the average number of years people rely on Medicare for their health insurance coverage, which places greater financial pressure on the Medicare program.

A deferral in Medicare eligibility would be expected to reinforce incentives in the Social Security system for workers to delay retirement and remain in the labor force, while at the same time enabling older Americans to save more for their expenses during retirement, pay payroll taxes to help support Medicare and Social Security, and pay taxes that help to strengthen the economy. Because many people choose to apply for Social Security and Medicare at the same time, CBO reports that raising the Medicare eligibility age would also reduce Social Security retirement benefit outlays in the short term.

The coverage expansions included in the ACA can help to alleviate the concern previously held about raising the age of Medicare eligibility, that 65- and 66-year-olds would be at high risk of becoming uninsured in the absence of Medicare. As mentioned earlier, with full implementation of the ACA, 65- and 66-year-olds would have access to health insurance coverage through the health insurance exchanges and Medicaid (assuming conforming technical changes are made to the law to facilitate coverage under the Medicaid expansion), with subsidies available to those with incomes up to 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

Opponents cite a number of concerns with this option. Raising the age of eligibility would reduce Medicare spending, but also would shift costs from Medicare to other payers, which would result in a net increase in health care spending system-wide (Kaiser Family Foundation 2011). An increase in the Medicare eligibility age would result in higher premiums for those who remain on Medicare, because younger and relatively low-cost 65- and 66-year-olds would no longer be in the Medicare risk pool; higher premiums for younger adults getting private coverage through the health insurance exchanges because having 65- and 66-year-olds in that risk pool would increase the average cost of exchange coverage; higher costs for employers, to the extent that some of those no longer eligible for Medicare would be covered instead under an employer plan; and higher Medicaid expenditures as some lower-income people ages 65 and 66 would be eligible for coverage under that program.

For people ages 65 and 66, the effects of losing Medicare eligibility would be mixed. People with relatively modest incomes (less than 300 percent of the FPL) would be expected to have lower out-of-pocket costs under their new source of coverage, on average, than they would if covered by Medicare, but the majority of 65- and 66-year-olds with relatively higher incomes (greater than 300 percent of the FPL) are expected to face higher out-of-pocket costs because their private sources of coverage would be more expensive than under Medicare and they would receive less generous or no subsidies for private exchange coverage (Kaiser Family Foundation 2011). And while the ACA provides new coverage options, some low-income 65- and 66-year-olds might not be able to get coverage under the Medicaid expansion if they live in a state that chooses not to expand its Medicaid program. Another concern cited by opponents is the uneven effects on people ages 65 and 66 of raising the Medicare eligibility age due to differences in life expectancy by race, income, and gender. For example, life expectancy at age 65 is nearly two years shorter for black men than white men and one year shorter for black women than white women, on average (NCHS 2012).

OPTION 1.2

Raise the Medicare eligibility age to 67 for people with higher lifetime earnings

Under this option, all qualifying workers would get Medicare benefits but the timing of their eligibility for benefits would differ by income, with beneficiaries’ lifetime earnings determining when they would become eligible for Medicare (Emanuel 2012).22 Beneficiaries in the top quarter of the lifetime earnings distribution would not be eligible for Medicare until age 70; those in the next highest quarter of lifetime earnings distribution would be eligible at 67; and those in the lower half of the lifetime earnings distribution would continue to be eligible at age 65. Both of the higher-earnings groups would be permitted to buy into Medicare at age 65 until they reach the eligibility age for their lifetime earnings quartile.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Many of the advantages and disadvantages of Option 1.1 also pertain to this option. Adjusting the age of Medicare eligibility by income would take into account the fact that the wealthy, on average, live longer than those in lower-income brackets, which could address concerns that raising the age of Medicare eligibility for all 65- and 66-year-olds would adversely affect those with shorter average lifespans. Raising the eligibility age for Medicare according to lifetime earnings could also encourage more personal savings, as people may prepare differently for health expenses in retirement if they know they will not (or may not) be eligible for Medicare until after age 65.

There are issues to be considered when using a measure based on lifetime earnings. On the one hand, lifetime earnings are considered to be a more stable measure of wealth than income in a particular year or over a limited number of years, but on the other hand, lifetime earnings may not be a good indicator of a person’s financial situation at the time they age on to Medicare, especially if they have experienced a recent change in employment status.

An additional concern relates to the administrative feasibility of this proposal. While information related to earnings is collected by the Social Security Administration and disseminated to all workers who pay employment taxes, a number of questions arise with respect to how lifetime earnings would be calculated and how the policy would be implemented, including: (1) How would lifetime earnings be measured and over what time period? (2) How far in advance of age 65 would a prospective beneficiary be informed of their age of Medicare eligibility? (3) Which agency or agencies of the Federal government would be responsible for making income determinations, resolving discrepancies, and communicating income determinations to beneficiaries? (4) What are the implications of using a measure based exclusively on earnings for individuals with relatively low earnings but substantial unearned income?

References

Click to expand/collapse

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2012. Health, United States, 2011, May 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012. Raising the Ages of Eligibility for Medicare and Social Security, January 2012.

Amy J. Davidoff and Richard Johnson. 2003. “Raising the Medicare Eligibility Age: Effects on the Young Elderly,” Health Affairs, July/August 2003.

Ezekiel Emanuel. 2012. “Entitlement Reform for the Entitled,” The New York Times, May 20, 2012.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2011. Raising the Age of Medicare Eligibility: A Fresh Look Following Implementation of Health Reform, July 2011.

.

Beneficiary Cost Sharing

Options Reviewed

This section reviews several options for reducing Medicare spending by increasing or modifying beneficiary cost sharing:

» Increase the Part B deductible

» Introduce cost sharing for home health services

» Introduce cost sharing for the first 20 days of a skilled nursing facility (SNF) stay

» Introduce cost sharing for clinical laboratory services

» Modify current cost-sharing requirements to reflect “value-based insurance design”

» Restrict first-dollar supplemental coverage or establish a supplemental coverage surcharge

Increasing deductibles and cost sharing for Medicare-covered services would reduce Medicare spending by shifting cost obligations from the Federal government to people on Medicare. In addition, Medicare may achieve savings that result from reduced utilization of Medicare-covered services to the extent that beneficiaries choose to forego medical care—potentially both necessary and unnecessary services—to avoid higher costs. The effects for beneficiaries would be expected to vary based on income, health status, and their supplemental insurance coverage. Increasing Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements also could affect costs incurred by other payers, including the Medicaid program and employers who provide supplemental coverage for retirees on Medicare.3 A related option would modify cost-sharing requirements to encourage the use of higher-value care and discourage the use of lower-value care.

Background

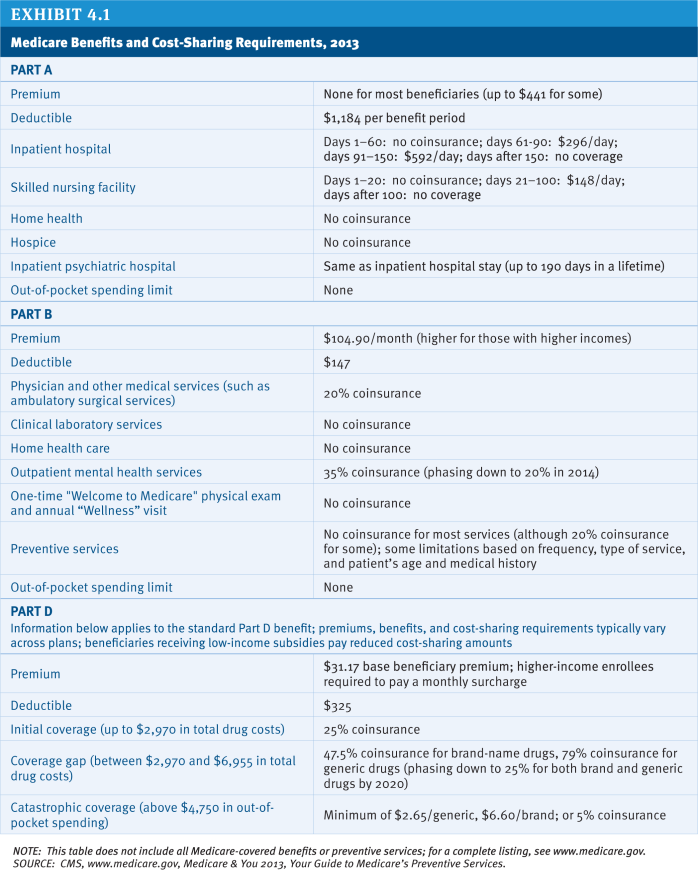

Medicare has a complex benefit design, with a deductible for inpatient services covered under Part A, another deductible for physician and other outpatient services under Part B, and a separate deductible for prescription drugs under the standard benefit design covered by Part D plans. Medicare also imposes cost-sharing requirements that vary by type of service. Unlike typical large employer plans, traditional Medicare does not have an annual limit on out-of-pocket spending for services covered under Parts A and B (although Medicare Advantage plans are required to include a limit on out-of-pocket costs for Medicare-covered services).

Due to the relatively high cost-sharing requirements and the absence of a limit on out-of-pocket spending, the vast majority of people with traditional Medicare have some type of supplemental insurance to help cover these costs, such as an employer-sponsored retiree health plan, a private Medicare supplemental insurance (Medigap) policy or, for those with low income, Medicaid. However, even though supplemental coverage helps to defray these expenses, out-of-pocket medical costs (including premiums) are a concern for many people with Medicare and have been rising as a share of income (Kaiser Family Foundation 2011a). With a median income for individual Medicare beneficiaries of $22,500 in 2012, health expenses consume a relatively large share of beneficiaries’ incomes and household budgets (Kaiser Family Foundation 2011a; Kaiser Family Foundation 2011c; Kaiser Family Foundation 2012) (Exhibit 1.2) (Exhibit 1.3).

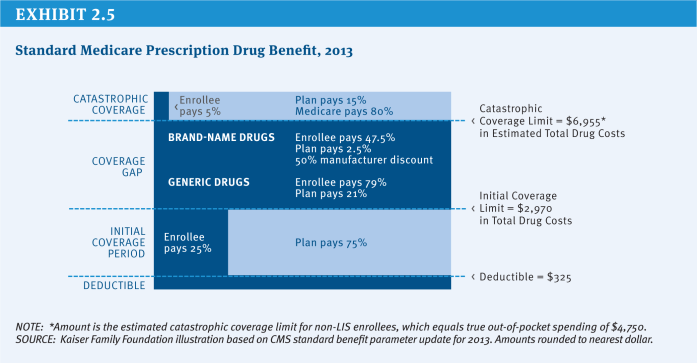

A number of recent proposals have recommended various options to increase or modify deductibles and cost-sharing requirements for some or all Medicare beneficiaries. Some analysts assert that people with Medicare should bear part of the burden of Medicare savings, citing research indicating that the average beneficiary receives more in Medicare benefits than they have paid into the program during their working years (Steurle and Quakenbush 2012). Some also hope that changes in cost sharing would encourage beneficiaries to consume more high-value (i.e., higher-quality and lower-cost) services and fewer low-value services, just as tiered cost sharing has encouraged Part D enrollees to use lower-cost generic or preferred-brand drugs when available, producing savings for Medicare and for beneficiaries. However, others argue that beneficiaries should be protected from increases in cost sharing, especially those with low incomes.

Changes to Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements could produce a number of different outcomes. Higher cost-sharing requirements for specific services would reduce Medicare spending, while increasing costs for users of these services and for other payers. Making beneficiaries responsible for a greater share of their health costs would likely reduce the demand for care. Research demonstrates that people may forgo both unnecessary and necessary care in response to higher out-of-pocket costs (Swartz 2010). To the extent that beneficiaries forego necessary services and subsequently are hospitalized or visit an emergency department to treat preventable illnesses, the savings from higher cost sharing and reduced utilization could be offset in part or in whole by new Medicare spending. Under many of these approaches, the existence of supplemental coverage such as Medigap and employer-sponsored retiree health policies complicates the financial effects of cost-sharing changes.

This section describes several options to raise or modify deductibles and cost sharing, but does not present policy changes that could be considered in conjunction with these options that would strengthen financial protections for low-income beneficiaries, many of whom would be disproportionately affected by new cost sharing. Nor does it present options that would improve benefits, such as by adding a new limit on out-of-pocket spending for Part A and Part B services. The report includes a separate discussion of more comprehensive options that would restructure Medicare’s benefit design (see Section Four, Benefit Redesign).

Policy Options

OPTION 1.3

Increase the Part B deductible

The Part B deductible ($147 in 2013) is relatively low when compared with private coverage, while the Part A deductible ($1,184 in 2013) is relatively high. Under current law, the Part B deductible is indexed to rise with the growth in Part B per capita expenses and, as such, is projected to increase to $226 by 2021 (Boards of Trustees 2012).

This section describes two options to achieve savings by raising the Part B deductible:

» Option 1.3a: Increase the deductible incrementally by $75 for new beneficiaries only. This option was included in President Obama’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2013 Budget and would increase the Part B deductible for new enrollees by $25 in each of 2017, 2019, and 2021 (OMB 2012).

» Option 1.3b: Increase the deductible by $75 for all beneficiaries.

Budget effects

CBO estimated that Option 1.3a, as proposed in President Obama’s FY 2013 Budget, would save the Federal government $2.3 billion over 10 years (2013–2022) (CBO 2012). The savings would increase over time as new people become eligible for Medicare.

Although official government estimates are unavailable for Option 1.3b, analysis conducted by the Actuarial Research Corporation (ARC) for the Kaiser Family Foundation projects Federal savings of $32 billion over 10 years (2014–2023) if the policy were implemented in 2014. This estimate is considerably higher than that for President Obama’s proposal because the increase would apply to all beneficiaries, would be implemented in an earlier year, and would begin immediately, rather than incrementally.

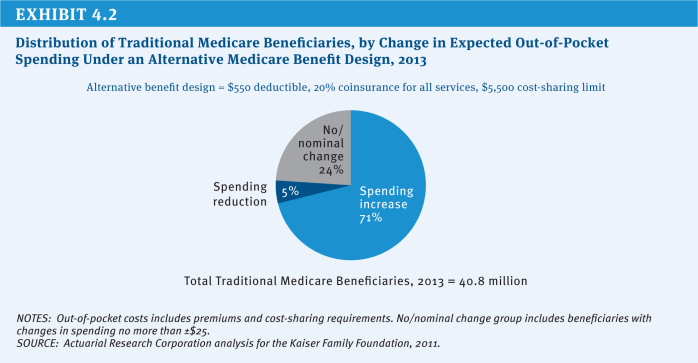

Discussion

Increasing the Part B deductible would produce Federal savings and could make beneficiaries more cost-conscious about their use of physician and outpatient services. However, it also would increase costs for beneficiaries and other payers. According to ARC’s analysis, a $75 increase in the deductible for new enrollees in 2014 (similar to Option 1.3a, but implemented earlier) would raise costs for 5 percent of beneficiaries initially, although that share would grow over time as more people join Medicare. Raising the deductible by $75 for all enrollees in 2014, as in Option 1.3b, would increase cost-sharing obligations for the vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries.4 Supplemental plans that cover the deductible would moderate the effect of the cost-sharing increase for enrollees. This would, in turn, increase supplemental plan premiums and increase spending by employers and Medicaid. Those without supplemental coverage who use Part B services would incur the increase in the deductible directly. Part B premiums, set to cover 25 percent of Medicare Part B spending, would be expected to fall because the higher deductible would result in lower Part B expenditures.

OPTION 1.4

Introduce cost sharing for home health services

Medicare home health services are not subject to a deductible or cost-sharing requirements. Medicare covers home health services through both Part A and Part B, the former for up to 100 visits following an inpatient or skilled nursing facility (SNF) stay and for beneficiaries who are not covered under Part B, and the latter for all other visits (CRS 2010). Medicare home health utilization has risen relatively rapidly in recent years. Between 2002 and 2010, the number of home health users increased by 36 percent (from 2.5 million people to 3.4 million people), the annual number of episodes per user increased from 1.6 to 2.0, and the number of episodes of care increased by 66 percent, from 4.1 million to 6.8 million (MedPAC 2012b). The growth in home health care has been especially large among episodes that are not preceded by a hospitalization or post-acute care, which now comprise nearly two-thirds of home health episodes (MedPAC 2012b).

In 2010, Medicare spent $19.4 billion on home health services, up from $8.5 billion in 2000 (MedPAC 2012b). As part of a settlement agreement resulting from a Federal class action lawsuit, CMS could soon expand coverage of home health services by clarifying that beneficiaries who do not demonstrate a potential for improvement may still be eligible for coverage; it is not clear whether this change will lead to an increase in spending over time (Jimmo v. Sebelius 2012).

This section reviews three options for imposing cost sharing on home health services:

» Option 1.4a: Impose a 10 percent coinsurance on all home health episodes. In 2008, a 10 percent coinsurance on the average home health episode would equal about $300 (MedPAC 2011).

» Option 1.4b: Impose a $150 copayment per full episode, that is, episodes encompassing five or more visits. This $150 copayment represents approximately 5 percent of the average cost of a home health episode (as of 2008) (MedPAC 2011).

» Option 1.4c: Impose a $150 copayment per full episode, restricted to episodes that do not follow a hospitalization or post-acute care. In 2011, MedPAC recommended a copayment for episodes that do not follow a hospitalization or post-acute care, noting the rapid growth in volume of these types of episodes. President Obama’s FY 2013 Budget included a $100 copayment per full episode that does not follow a hospitalization or post-acute care, although this would only apply to new beneficiaries beginning in 2017 (OMB 2012).

Budget effects

The effects of home health cost sharing on program spending and beneficiaries would depend on several factors, including whether the cost sharing is imposed per visit or per episode, whether it applies to all episodes or a subset (e.g., those that do not follow inpatient or post-acute care), whether it applies to all beneficiaries or just new enrollees, and the implementation date.

» Option 1.4a: In 2011, CBO estimated that this option would produce Federal savings of $40 billion over 10 years (2012–2021) if implemented in 2013.

» Option 1.4b: No official government cost estimate is available for this option. According to ARC, a $150 copayment per full episode would produce Federal savings of $19 billion over 10 years (2014–2023).

» Option 1.4c: In 2011, MedPAC estimated that this option would produce between $1 billion and $5 billion in Medicare savings over five years. In 2012, CBO estimated that the Obama Administration proposal (a $100 copayment for this subset of episodes applied to new beneficiaries beginning in 2017) would produce Federal savings of about $0.3 billion from 2013 to 2022. Savings would increase over time as more people became eligible for Medicare.

Discussion

A new cost-sharing requirement for home health care would reduce Medicare spending and could address some concerns about overutilization. Home health cost sharing may also be helpful in that it could give beneficiaries information that could be used to identify and report possible instances of fraudulent billing. At the same time, this option would increase costs for beneficiaries who use these services, employers, and others.

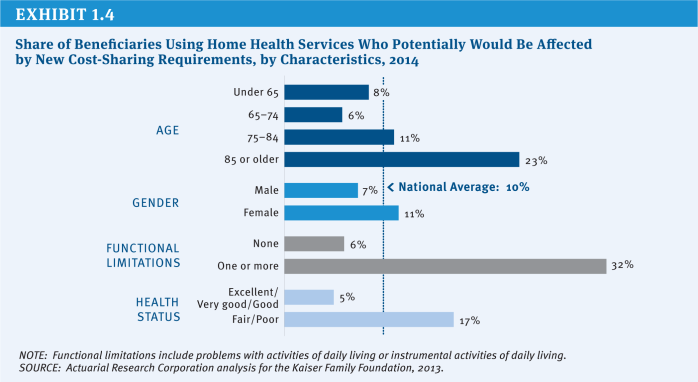

ARC has projected that one in ten beneficiaries (10 percent) will use home health services in 2014, and all would be affected by a 10 percent coinsurance. However, some groups of beneficiaries are more likely to use home health services and would be disproportionately affected by new cost sharing, including beneficiaries with lower incomes and not covered by Medicaid, those ages 85 and older, women, those in relatively poor health, and those with functional impairments (Exhibit 1.4).

The effects of the three different options would differ in terms of how many beneficiaries would be affected, which beneficiaries would be affected, and how much cost sharing they would face. The 10 percent coinsurance would affect all home health users (or, according to ARC, roughly 3.8 million beneficiaries if implemented in 2014), while the $150 copayment would affect the majority of home health users (about 3.2 million beneficiaries if implemented in 2014). A more limited copayment, applied to those without an inpatient stay or post-acute care, would affect fewer beneficiaries (1.4 million).

In contrast to the coinsurance option (Option 1.4a), the two copayment options (Options 1.4b and 1.4c) would cap the cost-sharing obligation per home health episode, although users would pay more than $150 if they had multiple episodes. According to ARC, the average home health user would face $550 in new cost-sharing obligations with a 10 percent coinsurance—more than users would under the flat $150 copayment per full episode. Beneficiaries who use home health services more extensively would face larger increases in cost-sharing obligations with the coinsurance than the flat copayment. For example, among beneficiaries with functional impairments who use home health services, cost-sharing obligations would increase by an estimated $750, on average, with a 10 percent coinsurance.

To the extent that home health users pay the new cost sharing out of their own pockets, use of home health services would be expected to decline (which is factored into the ARC analysis). In some instances, this could occur without major implications for beneficiaries’ health, while in others, beneficiaries may forgo needed care, which could result in higher costs associated with preventable inpatient admissions.5

A new home health copayment could create incentives for beneficiaries to substitute care in one setting for another. For example, a home health copayment applied to services received following an inpatient stay could drive beneficiaries to seek care in a skilled nursing facility for which there is no copayment for the first 20 days. This would be less of a concern with a $150 copayment that is restricted to episodes that do not follow a hospitalization or post-acute care.

Home health users without supplemental coverage would be fully exposed to new cost-sharing requirements. Others would be protected from some or all of these new cost-sharing requirements to the extent that their supplemental insurance covers these expenses. Home health users with Medicaid (36% according to ARC analysis) would be shielded from new cost-sharing obligations if Medicaid assumed these expenses on their behalf, which would in turn increase Medicaid spending. Similarly, beneficiaries with Medigap or employer-sponsored supplemental coverage could be shielded from direct cost-sharing requirements, but premiums would be expected to rise as a result (along with costs for employers). Part B premiums would be expected to fall somewhat because they are tied to Part B per capita program expenses, which are projected to decline under this option.

Finally, a new home health copayment per episode would impose new administrative costs on Medicare and private entities, given that home health providers do not have to keep track of cost-sharing requirements for Medicare beneficiaries under current law.

OPTION 1.5

Introduce cost sharing for the first 20 days of a skilled nursing facility stay

Another option for achieving Medicare savings would be to add upfront cost sharing for short SNF stays. Under current law, Medicare covers SNF stays of up to 100 days per benefit period for beneficiaries who have been hospitalized for at least three consecutive days. Beneficiaries are not required to pay cost sharing for the first 20 days each benefit period, but face a daily copayment for days 21–100, set to equal 12.5 percent of the Part A deductible (or a projected $153 per day in 2014). On average, SNF users paid cost sharing for 23 days in 2010 (and those with cost sharing paid for an average of 36 days) (CMS 2011).

Budget effects

In 2011, CBO estimated that a daily copayment for the first 20 days of a SNF stay set at 5 percent of the Part A deductible would reduce Federal spending by $21.3 billion over 10 years (2012–2021), if implemented in 2013.

Discussion

Introducing an upfront copayment for SNF care could produce substantial Medicare savings. However, it would increase cost sharing for SNF users, a relatively small, but vulnerable, group of beneficiaries. According to analysis by the Actuarial Research Corporation (ARC) for the Kaiser Family Foundation, 4 percent of beneficiaries are projected to have a SNF stay in 2014, and would thus face new cost-sharing obligations under this policy. This would include a larger share of beneficiaries ages 85 or older, those with low incomes, those who report fair or poor health, and people with functional impairments.

With a copayment on the first 20 days set at 5 percent of the Part A deductible (projected to be $60 in 2014), cost-sharing obligations for SNF users would increase in 2014 by $920 on average. The average is somewhat less than $1,200 ($60 for the first 20 days) because some SNF stays are shorter than 20 days. To the extent that the additional SNF cost-sharing requirements are covered by Medigap and employer plans, premiums would be expected to rise for beneficiaries covered by these policies (as would employer spending). Because Medicaid pays cost sharing on behalf of Medicare beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, Medicaid spending would also rise.

A new copayment would be expected to have some impact on utilization of SNF services (which is factored into the analysis above). With higher front-end costs, the average length of stay would be expected to decline.

OPTION 1.6

Introduce cost sharing for clinical lab services

Currently, Medicare beneficiaries have no cost sharing for clinical lab services. One option to achieve savings would impose the same cost-sharing requirements on lab services as for other Part B services, applying the Part B deductible ($147 in 2013) and 20 percent coinsurance.

Budget effects

In 2008, CBO estimated that this policy would have reduced Federal spending by $24 billion over 10 years (2010–2019), had it been implemented in 2011.

Discussion

According to ARC analysis for the Kaiser Family Foundation, the majority of beneficiaries (85 percent) are expected to use clinical lab services in 2014. Implementing this policy would be expected to increase cost-sharing obligations for this group by an average of $60 in 2014, and 12 percent of beneficiaries would be expected to see increases in cost-sharing obligations of $100 or more.

Medigap insurance, employers, and Medicaid would help enrollees cover these new costs, but this would in turn mitigate the utilization impact and lead to relatively modest increases in plan premiums and employer and Federal and State Medicaid spending. Conversely, Part B premiums, which are tied to per capita program expenses, would fall slightly.

One concern raised with clinical lab cost sharing is that the administrative expenses for lab suppliers, beneficiaries, and insurers could be large relative to the new revenues collected, given the high volume but sometimes low payment for some tests. Relying on a copayment rather than a coinsurance may be easier to implement administratively. Some also argue that cost sharing would not have a substantial impact on utilization, given that lab work is often ordered as part of a physician visit and not as a discretionary stand-alone service. If so, most of the savings from clinical lab cost sharing could represent a cost shift from Medicare to beneficiaries and their supplemental plans, rather than savings from lower utilization.

OPTION 1.7

Modify current cost-sharing requirements to reflect “value-based insurance design”

Evidence about the value of services and providers can be used to provide care more efficiently and could produce savings as a result. One mechanism for doing this within Medicare would be to move towards a value-based insurance design (VBID). Value-based benefit changes would modify Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements in order to encourage beneficiaries to use higher-value services and providers, discourage lower-value services and providers, or promote healthier behavior (Fendrick 2009). For example, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) eliminated cost sharing in traditional Medicare for recommended preventive services. Cost sharing tied to the value of services could be applied broadly to all beneficiaries, or could be targeted towards those who may be more likely to benefit, such as people with particular conditions, especially severe forms of those conditions, or who are participating in disease management programs (Fendrick 2009).

One approach to moving towards VBID in the Medicare program would be to allow the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to make value-based changes to the Part A and Part B cost-sharing structures, as long as those changes did not affect the overall actuarial value of Medicare for beneficiaries. MedPAC recommended a similar policy as part of a broader package of changes to Medicare’s benefit design (MedPAC 2012a).6 This approach is designed to be flexible so that the cost-sharing structure can be updated over time as the evidence-base develops (MedPAC 2012c). Another approach would impose lower cost-sharing obligations for using “preferred” providers who offer discounts to Medicare or meet certain quality or efficiency thresholds (see Section Two, Provider Payments for a discussion of this option).

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Moving towards VBID could produce savings while minimizing the harm to beneficiaries or even making beneficiaries better off in terms of reducing costs and/or improving the quality of care. Some large employers have already begun to implement components of value-based insurance design in their health plans and many others have expressed interest in doing so (Choudry et al. 2010).

There are some practical complications, however. For one, identifying “high-value” and “low-value” services may be difficult given that the evidence base is still developing. The value inherent in many services may also depend on the particular clinical needs of beneficiaries. This may limit the usefulness of VBID or could suggest the need to tailor the benefit design to individual circumstances. Implementing VBID may be a challenge for traditional Medicare, given that beneficiaries are currently entitled to payment for services that are medically necessary, with cost sharing that is uniform across all beneficiaries. Finally, supplemental coverage could mute the impact of VBID on beneficiaries’ utilization decisions.

OPTION 1.8

Restrict “first-dollar” supplemental coverage or establish a supplemental coverage surcharge

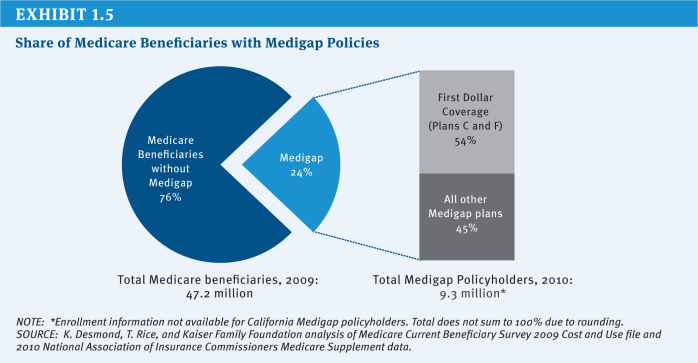

Another option would restrict supplemental coverage or require beneficiaries with this coverage to pay a surcharge. Most beneficiaries have some type of supplemental insurance to help pay Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements and fill gaps in Medicare’s benefit package. For example, in 2009, nearly a quarter of beneficiaries (24%) had a Medigap policy that supplements traditional Medicare and more than one-third (35%) had an employer-sponsored supplemental plan (these estimates include the 5 percent of beneficiaries who had both types of coverage).7

From the perspective of beneficiaries, supplemental plans provide protection from sudden and unpredictable medical expenses, alleviate the burden of ongoing everyday medical spending, and reduce the time spent on paperwork. Yet research has shown that comprehensive first-dollar coverage may lead people to obtain unnecessary services by protecting them from Medicare’s upfront cost-sharing requirements, although the estimates of the extra spending incurred by Medicare vary substantially. This in turn imposes costs not just on the supplemental policy, but on the Medicare program itself—costs borne by all beneficiaries and taxpayers.

Some have proposed to restrict this coverage in order to reduce Medicare spending or to recoup some of the additional costs of beneficiaries with first-dollar supplemental coverage by establishing a surcharge on supplemental plans. Proposals vary in terms of whether they would apply to all types of supplemental plans or just Medigap policies, whether or not they would be restricted to new enrollees, when they would be implemented, and whether they would target first-dollar coverage only or apply to all coverage. This section reviews three options:

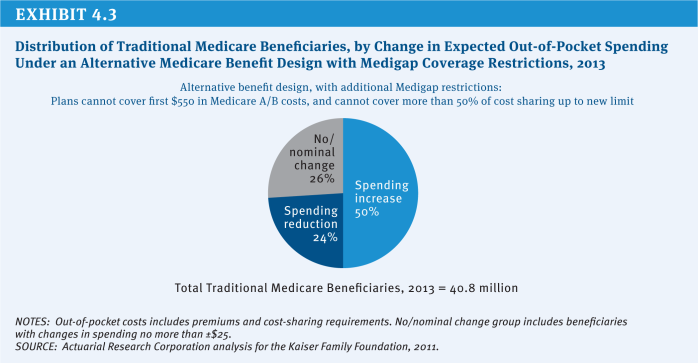

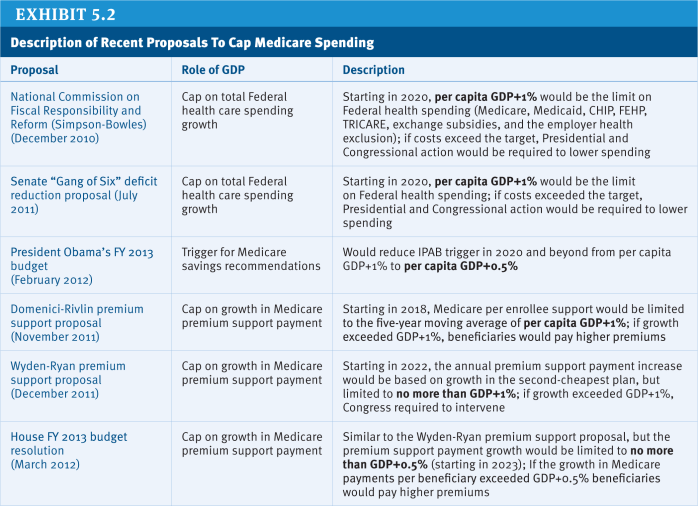

» Option 1.8a: Restrict first-dollar Medigap coverage. This option would prohibit Medigap policies from covering the first $550 of beneficiary cost-sharing obligations and limit coverage to 50 percent of the next $4,950 in cost sharing. This option was evaluated by CBO in 2011 and is similar to a recommendation made by the President’s National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (the Simpson-Bowles commission).

» Option 1.8b: Impose a 20 percent premium surcharge on all supplemental policies (both Medigap and employer plans). This option would retain beneficiaries’ current options regarding choice of supplemental plans, but would require them to pay a 20 percent surcharge in addition to their plan premium. The surcharge is intended to recover some or all of the additional costs that supplemental coverage may impose on Medicare. MedPAC recommended a premium surcharge on all supplemental plans (including both Medigap and retiree plans) as part of a broader proposal to restructure Medicare’s benefit design (MedPAC 2012a).

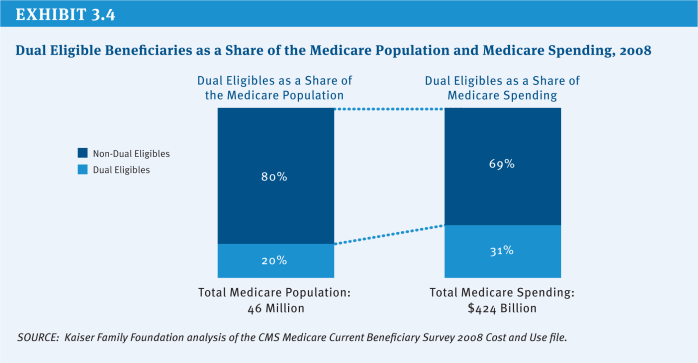

» Option 1.8c: Impose a 30 percent Part B premium surcharge for new enrollees who have “near first-dollar” Medigap coverage beginning in 2017. This option was included President Obama’s FY 2013 budget proposal. Although the budget proposal does not define “near first-dollar” coverage, it would minimally include Medigap Plans C and F, which provide first-dollar coverage and covered the majority of Medigap enrollees in 2010 (54 percent, and 13 percent of the overall Medicare population) (Exhibit 1.5).

Budget effects

CBO has estimated that restricting first-dollar Medigap coverage as described under Option 1.8a would produce Federal savings of $53 billion over 10 years (2012–2021) if implemented in 2013 (CBO 2011). CBO has not provided an estimate of Option 1.8b, although it estimated that a related (but narrower) version of this policy that would levy an excise tax on Medigap policies alone set at five percent of the plan premium would save $12 billion over 10 years (2009–2018) (CBO 2008). CBO also estimated that a 30 percent Part B premium surcharge for new enrollees with “near first-dollar” Medigap coverage beginning in 2017, as described under Option 1.8c, would save $2.6 billion over 10 years (2013–2022) (CBO 2012). Savings would increase as new people join Medicare.

The savings to Medicare from restrictions on Medigap are derived from expected reductions in utilization of medical services covered by the Medicare program as a result of greater price sensitivity among beneficiaries who would no longer have their cost sharing fully covered. In practice, the financial impact of surcharges is expected to come from: (1) the surcharges paid by beneficiaries who keep their supplemental coverage, which would be used to finance the extra costs currently imposed on Medicare, and (2) expected reductions in utilization and spending from beneficiaries who choose to drop their coverage or switch to a less generous plan. Actual savings would vary based on the extent to which beneficiaries drop or switch plans.

Discussion

Options to restrict or add a surcharge to supplemental coverage could produce savings for Medicare by reducing the indirect costs that supplemental coverage imposes on Medicare or recuperating the costs through a surcharge. In addition, because Part B spending would decline, Part B premiums would also decline for all beneficiaries.

The downside of these options is that they would limit beneficiaries’ ability to fully insure against the risk of unexpected medical expenses, exposing them to Medicare’s relatively high cost-sharing requirements, or they would require beneficiaries to pay more to insure against that risk. This could be especially burdensome for beneficiaries with modest incomes who do not qualify for Medicaid. In 2009, about two-fifths (41%) of beneficiaries with Medigap and/or employer coverage had incomes between $10,001 and $30,000.8

The effects on Medicare spending and beneficiary well-being would vary based on several key differences between specific proposals:

» Apply restrictions/surcharge to Medigap policies only or, more broadly, to all supplemental plans, including employer-sponsored retiree health coverage? Applying changes to employer plans could be viewed as more equitable in the sense that changes would apply to all supplemental policies rather than being targeted solely to Medigap policies. However, some might argue that retiree plans should be excluded, given that employees may have sacrificed additional earnings during their working years in exchange for retiree benefits. In addition, employer-sponsored retiree health plans generally do not provide first-dollar supplemental coverage. Including retiree health plan enrollees would affect a much larger share of beneficiaries; while about one-quarter (24%) of beneficiaries had Medigap coverage in 2009, more than twice as many (53%) had either Medigap or an employer-sponsored retiree health plan.9

» Apply restrictions/surcharge to first-dollar Medigap policies only or, more broadly, to all Medigap policies? Some proposals (including Option 1.8b above) would apply coverage restrictions or a surcharge on all Medigap policies, while other options more narrowly focus on policies that offer first-dollar coverage. Research suggests that cost sharing may have a greater impact on a patient’s decision of whether to seek care, but less of an impact once the patient has already sought medical care (Swartz 2010). Nonetheless, focusing on first-dollar policies may produce less savings than options that apply to all supplemental policies.

» Impose restrictions on supplemental coverage or impose a premium surcharge? A restriction on first-dollar supplemental coverage would more directly address concerns that first-dollar coverage leads to higher utilization of Medicare-covered services and spending, while a premium surcharge would give beneficiaries more flexibility to purchase their ideal level of insurance relative to a proposal that prohibits first-dollar coverage outright. However, a premium surcharge may discourage beneficiaries—especially those with limited incomes—from retaining or purchasing relatively comprehensive supplemental coverage.

» Apply restrictions/surcharge to all Medigap policyholders or, more narrowly, to new Medicare beneficiaries purchasing first-dollar Medigap policies? Under some proposals, changes to supplemental coverage would exclude beneficiaries who already have supplemental policies, as is the case under Option 1.8c. On the one hand, excluding current policyholders could be justified, given that existing Medigap policyholders may have purchased coverage with an expectation that they would retain access to guaranteed, renewable coverage in the future (and have paid premiums based on the value of this coverage under current law rules). On the other hand, excluding existing policyholders and applying changes only to those newly purchasing Medigap coverage would substantially reduce short-term savings, as indicated by CBO’s estimate of the President’s FY 2013 budget proposal.

» Apply surcharge to the Part B premium or Medigap premiums? This issue has distributional implications: applying a surcharge to the Part B premium would be nationally uniform and easier to administer, while applying a surcharge to Medigap premiums would result in differences due to the variation in Medigap premiums, which can vary by insurer, type of policy, and geographic area.

References

Click to expand/collapse

A.E. Benjamin. 1993. “An Historical Perspective on Home Care Policy,” The Milbank Quarterly, 1993.

Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. 2012. 2012 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, April 23, 2012.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2011. Medicare & Medicaid Statistical Supplement: 2011 Edition. November 2011.

Niteesh K. Choudry, et al. 2010. “Assessing The Evidence For Value-Based Insurance Design,” Health Affairs, 2010.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2008. Budget Options, Volume 1: Health Care, December 2008.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2011. Reducing the Deficit: Spending and Revenue Options, March 2011.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012. Analysis of the President’s FY 2013 Budget, March 2012.

Congressional Research Service (CRS). 2010. Medicare Primer, July 2010.

A. Mark Fendrick. 2009. “Value-Based Insurance Design Landscape Digest,” National Pharmaceutical Council July 2009.

Jimmo v. Sebelius. 2006. Proposed Settlement Agreement, October 16, 2012. Available at: http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Proposed-Settlement-Agreement.101612.pdf.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2011a. How Much “Skin in the Game” is Enough? The Financial Burden of Health Spending for People on Medicare,” June 2011.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2011b. Medigap Reform: Setting the Context, June 2011.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2011c. Projecting Income and Assets: What Might the Future Hold for the Next Generation of Medicare Beneficiaries? June 2011.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2012. Health Care on a Budget: The Financial Burden of Health Spending by Medicare Households, March 2012.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2011. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2011.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2012a. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, June 2012.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2012b. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2012.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2012c. Transcript of Public Meeting, April 5, 2012.