Why it Matters: Tennessee’s Medicaid Block Grant Waiver Proposal

On November 20, 2019, Tennessee submitted an amendment to its longstanding Section 1115 Waiver that would make major financing and administrative changes to its Medicaid program.1 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) certified the waiver as complete and opened a federal public comment period through December 27, 2019. Most significantly, Tennessee is requesting to receive federal funds in the form of a “modified block grant” and to retain half of any federal “savings” achieved under the block grant demonstration. The state identified five high-priority areas for reinvestment of such savings. Tennessee is also requesting authority to implement a closed formulary for prescription drugs and a waiver of all federal managed care oversight rules.2

Tennessee has a longstanding Section 1115 waiver, called TennCare II, through which most of its Medicaid program runs, dating back to 1994. Tennessee has not adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion, so excludes childless adults from coverage but covers parents up to 95% FPL (as of January 2019).3 The current waiver includes most enrollees and services, including most seniors, adults with physical disabilities, children with special health care needs,4 and children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). TennCare enrollees receive both acute care and long-term services and supports through mandatory capitated managed care arrangements. The state’s current waiver is set to expire in June 2021. In FY 2019, the Tennessee state legislature passed legislation requiring the state to submit a waiver amendment to CMS to request to convert their Medicaid funding mechanism to a “block grant” model under its TennCare waiver.5 If/when the state receives approval from CMS, the legislation requires the General Assembly to approve the agreement before implementation.

CMS has been developing guidance for states related to block grant waivers; however, CMS withdrew this guidance from Office of Management and Budget (OMB) review on November 15, 20196 – prior to Tennessee submitting its proposal. This will be an important waiver to watch as CMS decisions related to financing, treatment of budget neutrality, managed care regulations, and permanent waiver approval (among other areas) will send important signals to other states interested in pursuing similar program policies. This waiver will again test the limits of how the Administration and states can reshape the Medicaid program through Section 1115 waiver authority. This brief provides a high-level overview of the proposed waiver changes and context for why these changes matter.

The Tennessee waiver amendment proposes significant changes to Medicaid financing through a “modified block grant” with the potential for shared savings.

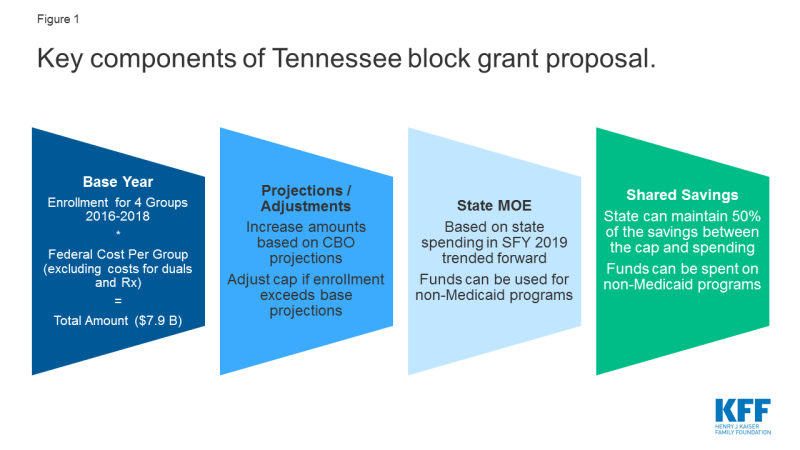

Under the proposal, Tennessee is requesting to receive federal Medicaid funds in the form of a “modified block grant.” Base spending for FY 2018 under the Tennessee proposal would be calculated based on average enrollment from state FYs 2016-2018 in four categories (blind and disabled, elderly, children, and adults) multiplied by expected “without waiver7” per member per month (PMPM) expenditure amounts by category (excluding costs for outpatient prescription drugs) multiplied by the Tennessee federal match rate (about 65%) (Figure 1). Spending estimates for 2018 would be trended forward based on Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections for growth in Medicaid spending to determine the block grant amount in the first year of the demonstration, which the state estimates to be $7.9 billion. These calculations to create a new “without waiver baseline” for waiver budget neutrality (as well as the block grant amount for measuring shared savings) could be, in part, related to compliance with CMS budget neutrality guidance released in 2018, scheduled to go into effect fully in January 2021.8 The state is proposing to exclude the following expenditures from its modified block grant model: administrative expenses, uncompensated care funds, spending for all dual eligible beneficiaries (full benefit and partial duals), and spending for services carved out of the Section 1115 waiver (e.g., services provided under the state’s separate Section 1915 (c) waivers for some people with I/DD and institutional I/DD services).

Unlike a typical block grant, federal funding would increase if enrollment grows. Base year spending would increase by spending growth estimated by CBO plus a per capita adjustment if actual enrollment exceeds enrollment estimates for the 2016-2018 base period. In this way, the block grant would set a federal financing floor. Federal funding would not decrease if enrollment were to decline. However, there would be no additional adjustment if per enrollee costs rise faster than anticipated (e.g., due to the development of new drug therapies or other advances or the emergence of public health crises (like the opioid epidemic)). The CBO per enrollee spending projections over the next decade are above inflation.9 The state does not anticipate that the block grant would reduce overall federal Medicaid spending in the state.

Under its proposed modified block grant, Tennessee would no longer draw down federal dollars based on a fixed federal match percentage and on state spending for covered beneficiaries and services.10 Tennessee proposes that it would be required to maintain state Medicaid spending at 2019 levels (trended forward for each block grant demonstration year). However, the proposal does not require such state spending to be for Medicaid-only services. While Tennessee notes that it expects that the “bulk” of block grant funds will be spent on “traditional” expenses (i.e., expenditures for medically necessary covered services), it proposes to have flexibility to spend federal block grant funds on services that may not otherwise be covered by Medicaid. Specifically, the state notes it would like the flexibility to spend federal funds on services not currently covered by Medicaid (or eligible for federal match) if the state determines such expenditures will benefit the health of enrollees or are likely to lead to improved health outcomes.

In any year that the state does not spend its entire federal block grant amount, Tennessee is proposing to share equally in the savings with the federal government. Each year, CMS would project the total amount of state and federal dollars that would have been spent without the waiver. The total amount of state and federal dollars actually spent during the year would be subtracted from CMS’s projected “without waiver” total. The difference would be multiplied by the state’s federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) to determine the federal share of the savings. That amount would be multiplied by 50% to determine the federal savings that could be retained by the state.11 So, the state would retain their “state share” of any block grant savings as well as 50% of the federal share.12

Tennessee says that it does not intend to restrict eligibility or benefits; however, the proposal does not require the state to maintain its current eligibility or benefits and the shared savings provision could create an incentive to reduce eligibility or benefits so that the state can achieve savings. Tennessee identified the following five priority areas as examples of areas where the state may invest such savings: extending coverage for postpartum women from two to 12 months; providing dental benefits only for prenatal and postpartum women; covering additional “needy” individuals who are not currently eligible; clearing the waiting list for home and community-based services for individuals with intellectual disabilities; and addressing other state-specific health crises.13 Under current federal law, the state could expand eligibility and/or optional benefits and receive federal matching funds to address these “high priority” areas. However, any expansion of coverage or services resulting from the availability of shared savings would likely remain dependent on the continued availability of such demonstration savings.

Capped federal financing with a potential for shared savings could incentivize the state to reduce optional eligibility and services for high cost enrollees.

Spending for non-dual seniors and persons with disabilities – who on average have high health needs and associated costs – would be included in the block grant.14 Tennessee estimates that this includes approximately 64,000 member months for non-dual seniors (about 5,300 enrollees) receiving capitated managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS), including non-dual seniors receiving MLTSS in nursing facilities or in the community. These seniors are not dually eligible likely because they do not have a qualifying work history to gain Medicare eligibility. The block grant would also include approximately 1.6 million member months for people with disabilities (about 133,000 enrollees) including adults with physical disabilities receiving MLTSS in nursing facilities or in the community, children who are eligible based on a disability (i.e., receive SSI) or are otherwise identified as blind or disabled (e.g., from claims), and adults and children with intellectual or developmental disabilities receiving home and community-based services.15

New coverage for children with disabilities and/or complex medical needs included in a separate waiver amendment pending at CMS would be excluded from the block grant. Directed by state legislation, Tennessee currently has a separate Katie Beckett-like waiver program amendment pending at CMS that would add coverage for some children with special health care needs. At least for the first several years, Tennessee proposes that this and any other new coverage groups would be excluded from the block grant, so that the state could gain experience paying for services before adding to the block grant calculation.

Seniors and people with disabilities account for a small share of enrollees but a large share of expenditures, placing these groups at higher risk under a capped financing model. While the state says the intent of the waiver is not to restrict eligibility or benefits, placing a cap on federal funding as well as an incentive to spend below the cap could lead the state to reduce optional eligibility or benefits to achieve these savings (which would not be prohibited under the terms of the waiver). Because seniors and people with disabilities often need complex acute and long-term care services, which are high cost and unavailable through other coverage sources, these groups may be particularly vulnerable to financing models that incentivize lowering costs to realize savings. Nearly all home and community-based long-term services and supports and most coverage pathways for seniors and people with disabilities are optional. Tennessee can scale back this coverage under current law. However, this proposal could create additional incentives to do so to access shared savings.

Beyond financing, Tennessee is seeking unprecedented flexibility to administer its program.

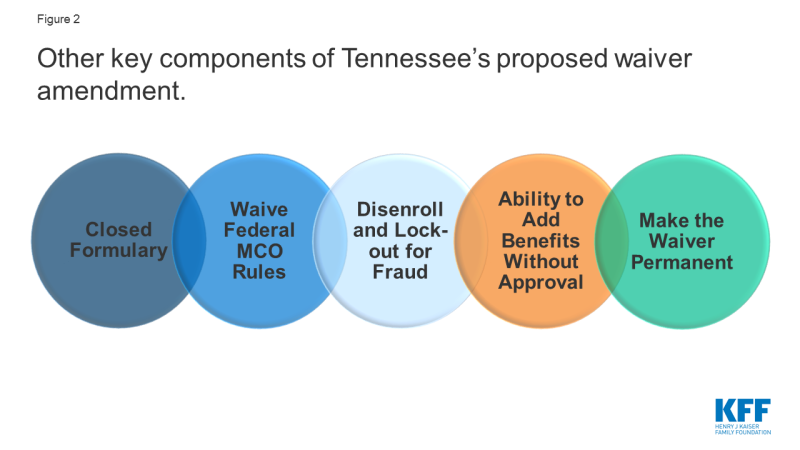

Tennessee is seeking authority to implement a closed formulary for prescription drugs (Figure 2). Under current rules, manufacturers that want their drugs covered by state Medicaid programs must rebate a portion of drug payments back to states (who share these rebates with the federal government). In exchange, Medicaid programs must cover almost all FDA-approved drugs produced by those manufacturers. Although states are required to cover nearly all of the manufacturer’s FDA-approved drugs, states employ a range of strategies to control prescription drug costs and utilization. The Tennessee proposal excludes outpatient prescription drugs from the block grant calculation but also seeks authority to implement a closed formulary, which would allow the state to cover just one drug per therapeutic drug class. The state is not proposing to forgo statutory rebates from drug manufacturers. The state is also proposing to exclude new drugs from the formulary until “market prices are consistent with prudent fiscal administration” or sufficient data exists regarding the drug’s cost effectiveness.16 A similar proposal put forth by Massachusetts was not approved by CMS.17

Tennessee is also seeking authority to add covered benefits without CMS approval and a waiver of all federal Medicaid managed care regulatory requirements. Under current law, states have authority to add optional benefits and to increase the amount, duration, and scope of a benefit by submitting a state plan amendment (SPA) (or demonstration waiver amendment). The Tennessee proposal would allow such changes without CMS approval. However, Tennessee would continue to submit SPAs to CMS for any changes that would eliminate or decrease benefits. The proposal also seeks to waive the managed care regulations at 42 CFR Part 438, which detail parameters involving how states contract with and oversee managed care plans. These regulations are extensive and outline federal requirements related to plan enrollment and disenrollment, network adequacy, utilization management, care coordination, member appeals, actuarially sound rates, quality strategies, program integrity as well as other areas.

Tennessee seeks authority to terminate enrollees from coverage and impose up to a 12-month lock out if an individual is determined to be guilty of TennCare fraud. The state seeks to determine additional details through state policy (e.g., when termination is appropriate, the length of the suspension) based on the nature of the offense and does not include these details in the waiver proposal. The state further notes that under certain circumstances it may choose to develop alternatives to termination or suspension of coverage including restricting access to certain benefits (e.g., pharmacy benefits for a member who fraudulently obtained prescription opioids) or conditioning continued coverage on specific member actions (e.g., participation in substance use disorder treatment for enrollees convicted of fraudulently obtaining prescription opioids). Under current federal law, enrollees suspected of fraud are referred to the appropriate law enforcement agency to make a determination of fraud with penalties assigned by the court (not the Medicaid agency),18 and states may not terminate or suspend Medicaid eligibility for individuals that remain eligible for the program.

Tennessee seeks exemptions from future federal requirements, additional flexibility to make program changes without CMS approval, and authority to have its waiver approved on a permanent basis. The proposal seeks exemptions from any new federal requirements as well as new flexibility to make changes to enrollment processes, service delivery systems, and the distribution methodology for the charity care and virtual disproportionate hospital share (DSH) funds without seeking CMS approval. Section 1115 waivers are typically approved for a five-year period and can be extended, usually for three years.19 Tennessee also proposes that CMS should authorize its demonstration on a permanent basis and only require future amendments to the waiver to go through the CMS approval process, which could result in less federal oversight and fewer opportunities for public comment.20

Looking Ahead

Tennessee’s proposed amendment is open for federal public comment through December 27, 2019. Some advocates have raised concerns that the federal public comment period is limited by holidays that fall within the time-period, which may constrain public engagement/comment and that the state has not provided sufficient detail in the current proposal to provide meaningful input on the proposed policy changes.21 Looking ahead, this will be an important waiver to watch as CMS decisions related to financing, treatment of budget neutrality, managed care regulations, and permanent waiver approval (among other areas) will send signals to other states interested in pursuing similar program policies. As a version of a block grant, the waiver mirrors longstanding conservative proposals to cap federal Medicaid spending while giving states added flexibility, which was also a prominent part of the debate to repeal and replace the ACA. However, Tennessee’s modified block grant proposal differs from a traditional block grant, as it would require the federal block grant calculation to adjust for enrollment growth, mitigating some risk for the state while creating a federal financing “floor” instead of a federal financing “ceiling.” This waiver proposal will again test the limits of how the Administration and states can reshape the Medicaid program through Section 1115 waiver authority.