The Role of Medicare and the Indian Health Service for American Indians and Alaska Natives: Health, Access and Coverage

SECTION 1: Key Characteristics of American Indians and Alaska Natives who are Age 65 and Older or Living with Disabilities

Among the 5.2 million people who identify themselves as either part or solely American Indian or Alaska Native, about 450,000 are age 65 or older. In total, based on the American Community Survey (ACS), about 1 percent of the U.S. population age 65 and over is American Indian or Alaskan Native, of whom about half report their race as solely American Indian or Alaska Native, and half report it in combination with another race. Women comprise a little more than half (56%) of the elderly American Indian and Alaska Native population—a rate that mirrors the overall U.S. population age 65 and over. (Limitations of the ACS and other data sources are discussed in text boxes 1 and 2).

The proportion of elderly people among American Indians and Alaska Natives is smaller compared with the proportion in the overall U.S. population. Specifically, 9 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives are age 65 and older, compared with 14 percent in the overall U.S. population. This difference reflects a younger median age and shorter life expectancy among American Indians and Alaskan Natives, attributable in large part to health disparities described later.1 By 2060, the number of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and older is projected to more than quadruple, growing to about 2 million—a rate that is nearly two times greater than the overall U.S. population age 65 and older.2

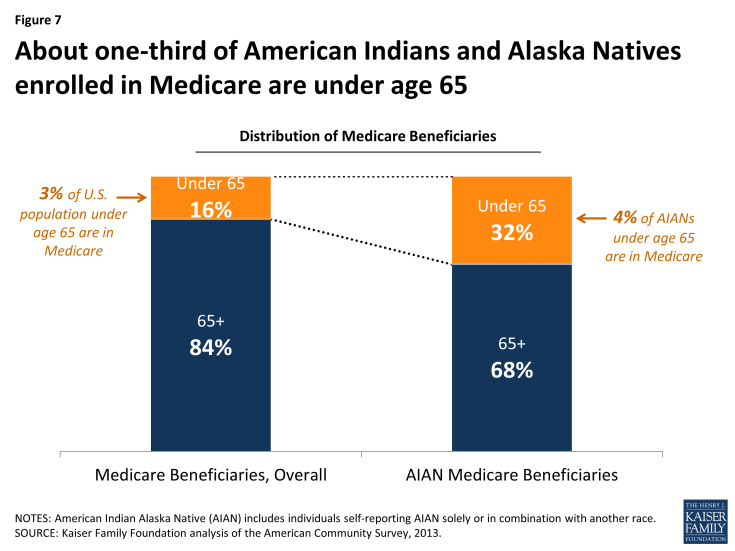

Another 200,000 American Indians and Alaska Natives under the age of 65 are living with a long-term disability (for which they receive Social Security Disability Insurance benefits) or a health condition, such as end stage renal disease, which qualifies them for Medicare. Approximately 4 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives under age 65 are enrolled in Medicare—similar to the 3 percent observed in the overall U.S. population. From self-reported data in the ACS and other surveys, it is difficult to determine the number of non-elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives living with long-term disabilities who might meet the requirements for Social Security Disability Insurance, but are otherwise not enrolled in Medicare.

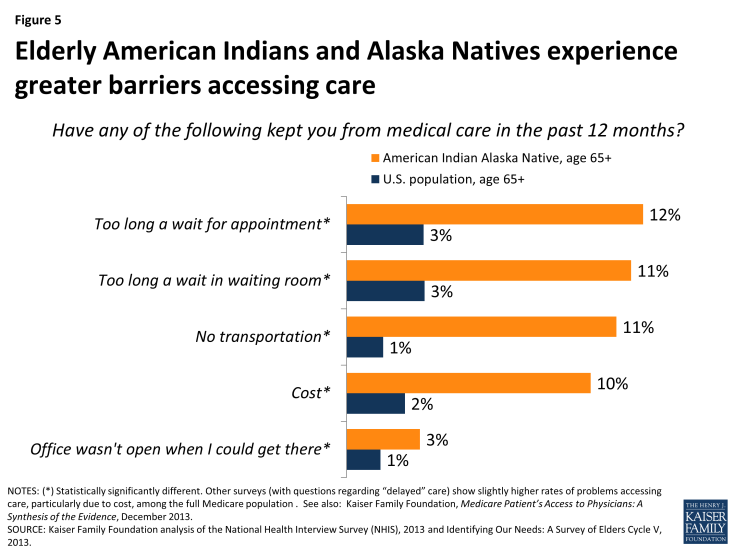

Older American Indians and Alaska Natives live throughout the country, but are concentrated in certain geographic areas. More than a third (35%) of all American Indians or Alaska Natives age 65 and older live in four states (California, Oklahoma, Texas and Arizona), and about half live in 8 states (Figure 1) (Appendix Tables 1-2). States with the highest concentration of American Indians and Alaska Natives among their 65 and older population are: Alaska, Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. While about 40 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives live in rural areas, only 22 percent currently live on reservations or land trusts.3 The remaining share lives in metropolitan or rural areas that are located outside of reservations or Land Trusts.4 The proportion of American Indians and Alaska Natives living away from reservations has grown steadily over time and this demographic shift is expected to continue.5 (Data specific to the share of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives living on reservations are difficult to verify, but as described later in this paper, about a third of Medicare beneficiaries report IHS as a source of health coverage, which may reflect their proximity to reservations and land trusts.) When American Indians and Alaska Natives live far from reservations, they may have little to no access to IHS-funded services, given the comparatively small scope of the Urban Indian Health Program described later in this issue brief.

Figure 1: American Indians and Alaska Natives, age 65 and older, live throughout the country, but are concentrated in certain states

Regardless of age, some American Indians and Alaska Natives belong to a federally-recognized tribe, some belong to a state-recognized tribe, and others are not members of a tribe. There currently are 566 federally-recognized sovereign tribes and more than 100 state-recognized tribes in the United States.6 Each tribe has its own eligibility requirements and unique customs and beliefs and more than 200 tribal languages are still spoken. Federally-recognized tribes share a government-to-government relationship with the federal government based around the “Federal Trust Responsibility.”7 Treaties and laws have established the federal government’s responsibility to provide federally-recognized tribes certain rights, protections, and services, including health care. In addition to American Indians and Alaska Natives who are members or descendants of members of federally-recognized tribes, IHS services are also authorized for “persons of Indian descent residing in the community being served.”8

Disparities in Income, Education, Health, and access to care

Compared to the overall U.S. population age 65 and older, American Indians and Alaska Natives in this age group have higher rates of poverty and lower educational levels. Analysis of the ACS shows that, among people age 65 and over, 16 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives report incomes that are at or below the federal poverty level, compared with 10 percent overall.9 Among younger American Indians and Alaska Native adults who qualify for Medicare because of a disability or other health condition, such as end stage renal disease, an even higher share (35%) report living in poverty. With regard to educational attainment, nearly three in ten (27%) American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and older did not complete high school, compared to about two in ten (19%) in the overall U.S. population age 65 and older.

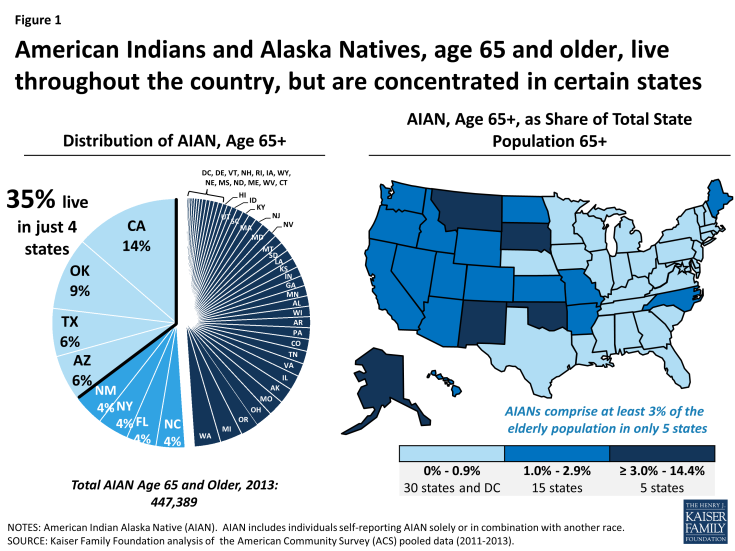

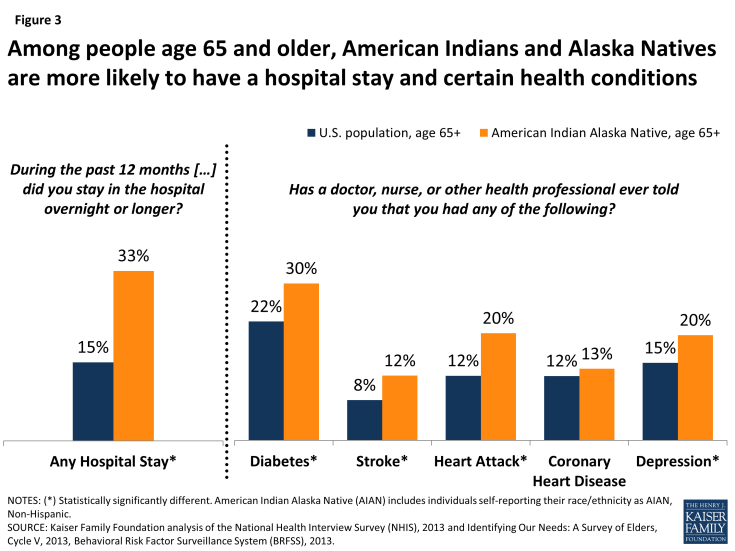

Elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives report having health problems at higher rates than the overall U.S. population age 65 and older. Turning to other surveys that focus on health issues, 39 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and over describe their overall health status as “fair” or “poor,” compared with a little more than 26 percent in the overall population age 65 and older (Figure 2). Further, elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives are hospitalized during the year at twice the rate of the overall population age 65 and older (33% vs. 16%), consistent with having higher rates of certain health problems (Figure 3). For example, nearly a third of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and over report having diabetes, compared with 22 percent in the overall 65+ population. While the prevalence of coronary heart disease is comparable between these groups, the share of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives with a previously diagnosed stroke or heart attack is higher compared with the overall population age 65 and older. Elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives also report more frequently that they suffered depression at some point in their lives, consistent with other research showing higher rates of mental illness among non-elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives.10

Figure 2: Elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives report poorer overall health compared with the general 65+ population

Figure 3: Among people age 65 and older, American Indians and Alaska Natives are more likely to have a hospital stay and certain health conditions

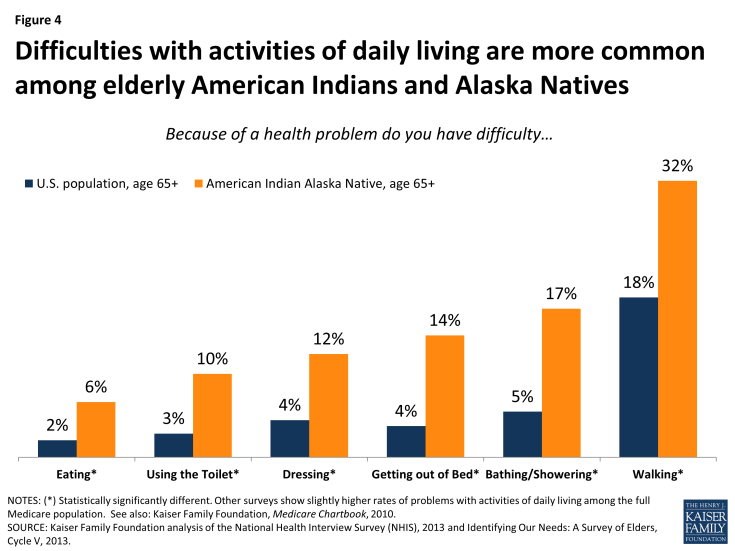

Limitations in activities of daily living are also more common among elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives than among the overall U.S. population ages 65 and older. Approximately one-third of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and older report trouble walking—nearly twice the rate observed for the overall population in this age group (Figure 4). Difficulties with other tasks, such as eating and dressing, bathing/showering are also more common for older American Indians and Alaska Natives. Not surprising, researchers have found that higher rates of functional limitations with activities of daily living are often associated with greater health needs.11 (Other surveys, with slightly different survey questions, show rates of functional limitations that are slightly higher).12

Figure 4: Difficulties with activities of daily living are more common among elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives

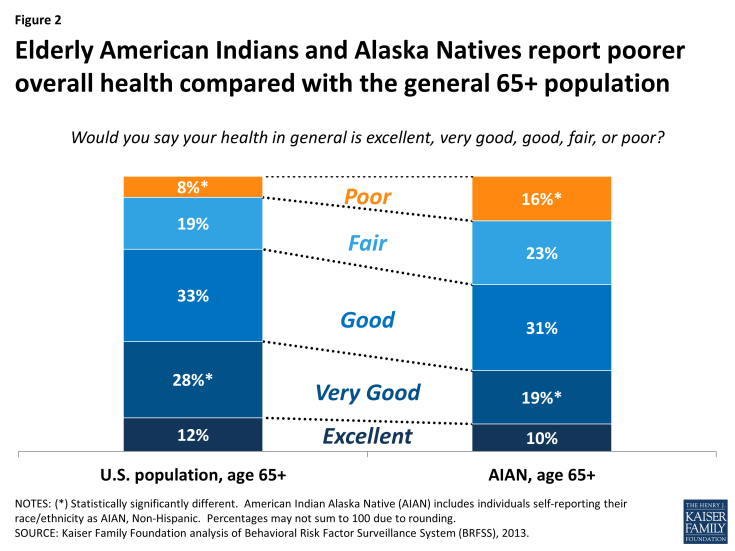

A higher share of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives report problems accessing care compared with the overall population age 65 and older. Given the health needs of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives, access to timely care is especially important for treatment of chronic conditions and other medical needs. As with the whole U.S. population age 65 and older, Medicare plays a key role for elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives in gaining access to health services. Nevertheless, elderly

American Indians and Alaska Natives report barriers to care more frequently than the overall population age 65 and older, particularly due to long wait times, lack of transportation, and cost (Figure 5). For example, compared to the general population age 65 and older, five times as many elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives reported that cost issues made them forego medical care—a likely reflection of their higher rates of poverty. Other associated access problems are harder to identify, but could include longer wait times in settings that provide care to medically underserved populations and challenges with transportation in remote and rural areas.

SECTION 2: Roles of the IHS, Medicare, and Other Sources of Coverage for American Indians and Alaska Natives

Role of the Indian Health Service

The IHS is the principal federal agency that fulfills the U.S. government responsibility to provide health care services to American Indians and Alaska Natives, regardless of whether or not they have health insurance coverage, including Medicare. Under this unique obligation, the Congress annually appropriates funds to the IHS—a federal agency within the Department of Health and Human Services—to deliver health care services to American Indians and Alaska Natives through a variety of facilities operated by either: the IHS, tribal entities, or Urban Indian Health Programs (I/T/Us). The overall mission of the IHS is to raise the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives to the highest level. Health care provided through IHS- and tribally-operated facilities is largely limited to members or descendants of members of federally-recognized tribes, who live on or near federal reservations and therefore have access to the facilities. In Alaska, tribally-operated health care facilities are located throughout the State and are not reservation based. 13 A small portion of IHS funding also supports Urban Indian Health Organizations to provide health care services to American Indians and Alaska Natives who may not live on or near reservations.

The IHS funds and provides health care and disease prevention services to American Indians and Alaska Natives, including those who may also be covered by Medicare, through a network of hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, and contractors. Patients at I/T/Us are generally not charged or billed for any portion of the services they receive, regardless of their insurance status. IHS funds 632 health care facilities, which are operated by either tribes or IHS. These facilities are located mostly on or near reservations.14 In addition, the IHS funds 35 Urban Indian Health Organizations in 57 sites located in cities throughout the U.S.15 Almost half (45%) of all Urban Indian Organizations are Federally Qualified Health Centers, serving other underserved populations as well.16

When IHS- or tribally-operated facilities are unable to provide needed care, the IHS has a limited budget to contract with outside providers to furnish health care services through the Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) Program, formerly called the Contract Health Services program, subject to available funding. Urban Indian Health Organizations are not provided funding to participate in the PRC program.

Overall, health care services provided through the IHS consist largely of primary care (mostly in the form of general outpatient and ambulatory care), but in some instances include ancillary and specialty services.17 Only a small subset of IHS facilities has surgeons or anesthesiologists to provide surgical services. The availability of IHS-provided skilled nursing care, home health services and hospice care, especially on or near the reservations, is also very limited.18 Lack of ready access to these services is particularly problematic for elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives as many of these services also tend not to be available through contract providers due to funding constraints. In cases where American Indians and Alaska Natives require specialty care that is not offered in an IHS or tribal facility, patients may be directed to PRC providers, but as described later in this brief, access to these providers is often limited to urgent medical conditions.

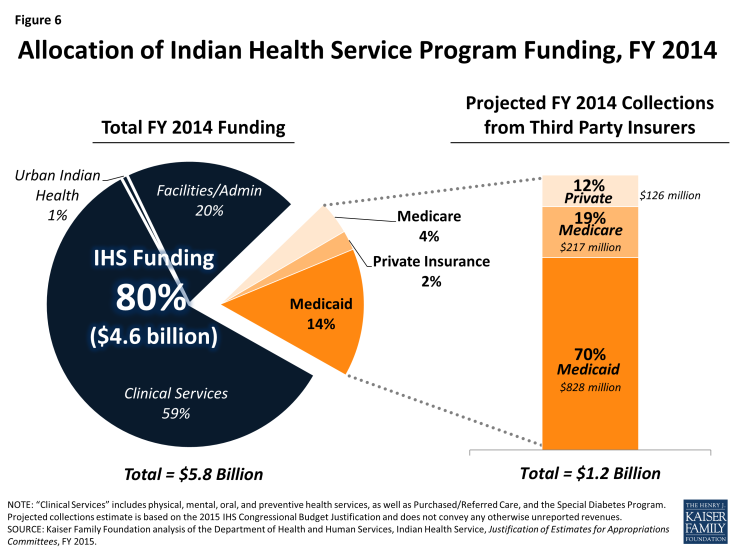

IHS funding is limited and must be appropriated by Congress each fiscal year. Federal funds are distributed through the Congressional appropriations process to IHS and tribal facilities across the country and provide the majority of their annual budgets. When service demands exceed available funds, services are prioritized or rationed, as described later in this brief. For 2014, Congress funded a total of $4.6 billion to IHS, with most ($3.4 billion) going towards clinical and preventive services (Figure 6). The remaining IHS funding was allocated for administrative and facility-management related activities such as equipment and maintenance, and 1 percent ($41 million) was allocated for Urban Indian Health programs.19

In addition to direct federal appropriations, revenues from third-party insurers, including Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance are a significant part (20%) of the operating budgets for IHS providers. Because IHS is the payer of last resort, IHS providers must collect payment from third-party insurers when providing services to American Indian or Alaska Native patients with health insurance.20 These collections help reduce financial shortfalls between capacity and need. In the aggregate, IHS programs operated with an estimated budget of $5.8 billion for FY2014—representing $4.6 billion (80%) from IHS appropriations and another $1.2 billion (20%) in collections from third-party payers (Figure 6).21 By far, the largest third-party payer is Medicaid, which accounts for $828 million or 70 percent of total third-party revenues to IHS providers. Medicare accounts for another $217 million in collections totaling 19 percent of third-party payments. IHS- and tribally-operated facilities forego potential revenue when serving uninsured patients who are eligible for other insurance programs, including Medicare and/or Medicaid, but have not enrolled in them.

Limited funding has impeded IHS’s ability to meet the health care needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Although the IHS discretionary budget has increased over time, funds are not equally distributed across IHS facilities and remain insufficient to meet health care needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives, as discussed in a previous Issue Brief by the Kaiser Family Foundation.22 Access to services through IHS varies significantly across locations, and American Indians and Alaska Natives who rely solely on IHS often lack access to needed care.23 Such access problems may be particularly problematic for people who are elderly or disabled, given their greater health care needs. Long waits to see physicians or get appointments at many IHS facilities are frequently reported.24 Funding to Urban Indian Health Organizations is also very limited and the share of IHS funding going toward urban programs over time has not reflected the overall demographic shift of American Indians and Alaska Natives away from reservations.25 Access to services through the Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) Program is considerably limited with available funding often running out before the end of the year, limiting care to only “medical priority-1 cases, or those that threaten life or limb.”26

Role of Medicare for American Indians and Alaska Natives

|

Summary of Medicare Benefits Medicare Part A, Hospital Insurance. Covers inpatient hospital care; generally no premium is required. When patients are hospitalized, they are subject to an inpatient deductible ($1,260 in 2015). Medicare Part B, Medical Insurance. Covers physician services, outpatient care and certain other services such as physical therapy and medical supplies. The monthly premium in 2015 for most is $104.90, but premiums are higher for those with higher incomes. Cost sharing includes an annual deductible ($147 in 2015) and coinsurance (which, for most services is 20% of Medicare’s approved amount). Part C or Medicare Advantage (MA). Provides coverage for Medicare Parts A and B through private health plans. A beneficiary may elect to enroll in an MA plan instead of enrolling in traditional fee-for-service Medicare. In addition to the Part B monthly premium, MA enrollees are charged a plan premium although that can be as little as $0 in some areas of the country. Depending on the MA plan, a deductible and coinsurance or copayments may apply to certain services. Part D or Prescription Drug Coverage—Covers outpatient prescription drugs. Most Medicare enrollees pay a monthly premium and copayments or coinsurance. |

Medicare is the federal health insurance program created in 1965 for people ages 65 and older, regardless of income or medical history, and expanded in 1972 to cover people under age 65 with permanent disabilities. Now covering 54 million Americans, Medicare plays a vital role in providing financial security to older people and those with permanent disabilities. Most people ages 65 and older, including American Indians and Alaska Natives, have and are entitled to Medicare if they or their spouse have made payroll tax contributions for 10 or more years. People who are under age 65 and living with a disability generally become eligible for Medicare if they are determined eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance and have received SSDI payments for a 24-month waiting period; other non-elderly people with certain health conditions, such as end stage renal disease, are eligible for Medicare with no waiting period.

Medicare consists of four parts (A, B, C and D) and covers a wide range of services, but there are some notable gaps. People with Medicare Parts A and B have coverage for inpatient and outpatient hospital care, physician care, and post-acute care, such as home health services, and care in skilled nursing facilities. In addition, Medicare covers outpatient prescription drugs for beneficiaries who enroll in a prescription drug plan (PDP) or through a Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug (MA-PD) plan. If I/T/U pharmacies exist in their service areas, PDPs and MA-PDs must provide convenient access to them for their members. In contrast, Medicare Advantage plans are not required to offer in-network contracts to I/T/Us for Parts A and B services.27 This may be a factor in the low rates of Medicare Advantage enrollment among American Indians and Alaska Native described in other research later in this brief and a text box 2.

While Medicare provides protection from many health care costs, it does not pay for some services vital to older people and those with disabilities, including long-term services and supports, dental services, eyeglasses, or hearing aids.

Medicare requires beneficiary cost-sharing for most of the health services that it covers. In addition to an annual deductible, beneficiaries in traditional Medicare are subject to other cost-sharing requirements with no limit on out-of-pocket spending. Like other Medicare beneficiaries, American Indians and Alaska Natives may have other sources of private coverage (such as retiree coverage from their previous employer) or Medicaid coverage for people with low incomes (also described below). These supplemental coverage sources may cover some or all of their Medicare cost-sharing amounts. When receiving services at I/T/Us or under referral through the PRC program, all patients, including Medicare beneficiaries, do not face any cost sharing, in general. In contrast, when American Indian and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries seek Medicare-covered services outside the IHS system, they are subject to the same Medicare cost-sharing requirements as other Medicare beneficiaries.

Because elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives are disproportionately low-income, many could be eligible for help from other programs in paying all or some of Medicare’s required cost-sharing. More specifically, low-income Medicare beneficiaries who meet eligibility requirements, based on their income and assets, may qualify under Medicaid for premium and cost-sharing assistance, and other benefits not covered by Medicare, such as long-term services and supports. Low-income Medicare beneficiaries who are not eligible for full Medicaid benefits may nevertheless be eligible for premium and cost sharing assistance through the Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs).28 Medicare provides premium and cost sharing assistance to low-income beneficiaries under Part D.29 In later sections of this brief, we present and discuss estimates of the numbers of low-income American Indians and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries who are also enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare Savings Plans, along with the data limitations of these estimates. In addition, we discuss the potential barriers that American Indians and Alaska Natives face in enrolling in these programs.

In addition, the IHS is another potential source of help for Medicare beneficiaries who are American Indians and Alaska Natives; the IHS is authorized to pay Medicare Part B (but not Part D) premiums on behalf of eligible American Indians and Alaska Natives. To date, IHS has not used this authority.30 Some individual Tribes, however, have elected to pay the Part B and Part D premiums for their members.31

Sources of Health care coverage for American Indians and Alaska Natives

Several factors make it difficult to determine the precise number of American Indians and Alaska Natives who are eligible for and covered by Medicare (Parts A, B and/or D). These factors include differences in definitions used to identify and categorize individuals as American Indian or Alaska Native, differences in survey methodologies, and long-standing inaccuracies in Medicare’s administrative data regarding beneficiary race and ethnicity.32 The discussion below relies mostly on estimates calculated from the American Community Survey (ACS)—the nationally representative survey with the largest sample of American Indians and Alaska Natives. It also discusses estimates from other publicly available surveys. A text box 1 provides further discussion about all these surveys and their limitations and the text box 2 examines challenges with using Medicare administrative files and claims data to identify American Indians and Alaska Natives in Medicare.

The majority of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives (up to 96%) report having Medicare coverage. When asked to list sources of health insurance coverage, 96 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and older list Medicare (Table 1). In addition to Medicare, many report having other sources of coverage that may assist with cost sharing requirements under Medicare. Almost one in four (24%) qualify for Medicaid supplemental coverage—for full benefits (full duals), or partially through the Medicare Savings Programs—due to low incomes, a substantially higher rate than is observed among the total U.S. population age 65 and older. Almost half (48%) of all elderly American Indian and Alaska Natives report having non-Medicaid supplemental coverage, which could include private insurance (such as a Medicare supplemental Medigap policy or retirement benefits from their employer), or other coverage through the Veterans Health Administration. With this survey, it is not possible to distinguish what portion of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in a private plan through Medicare Advantage.

| Table 1: Health Insurance Coverage for American Indians and Alaska Natives, By Age, 2013 | ||

| American Indians and Alaska Natives | Percent, by Type of Coverage | Number, by Type of Coverage |

| Age 65 and older | 447,389 | |

| Any Medicare | 96% | 428,575 |

| Medicare only | 28% | 119,510 |

| Medicare + Medicaid | 24% | 102,015 |

| Medicare + non-Medicaid supplemental | 48% | 207,050 |

| No Medicare, but other coverage | 2% | 9,588 |

| Uninsured | 2% | 9,226 |

| Under age 65 | 4,772,715 | |

| Any Medicare | 4% | 201,390 |

| Medicare only | 29% | 57,834 |

| Medicare + Medicaid | 52% | 105,577 |

| Medicare + non-Medicaid supplemental | 19% | 37,979 |

| No Medicare, but other coverage | 71% | 3,400,727 |

| Uninsured | 25% | 1,170,598 |

| Total (all ages) | 5,220,104 | |

| AIAN population in Medicare | 12% | 629,965 |

| NOTES: American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN). Medicare + Medicaid includes individuals with Medicare and full or partial Medicaid coverage. “Medicare + non-Medicaid supplemental” includes individuals with Medicare and additional non-Medicaid insurance, such as a Medigap policy, employer-sponsored retiree coverage, TRICARE, or Veterans Health Administration coverage. Uninsurance rates among the under-65 population is higher in analysis from previous years (2009-2011; see Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Coverage and Care for American Indians and Alaska Natives, October 2013). SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the American Community Survey, 2013. |

||

Notably, 28 percent of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives have Medicare, but no supplemental coverage and are, therefore, exposed to Medicare’s out-of-pocket cost sharing requirements unless receiving services from I/T/Us or through a PRC referral. About 4 percent of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives report that they do not have Medicare coverage, half of whom indicate that they are totally uninsured. Among American Indian and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries who are under age 65, more than half (52%) receive Medicaid coverage to supplement Medicare, signaling that a large proportion have low-incomes.

As mentioned, the ACS does not provide further distinctions about beneficiaries’ supplemental coverage, such as the shares enrolled in Medicare Savings Programs or in Medicare Advantage plans or the shares with prescription drug coverage (either through Medicare Advantage plans or through separate drug plans). Some researchers have turned to Medicare claims and administrative data for this information. We describe findings from this research in a text box 2, although there are a number of concerns identifying race and ethnicity using claims data.

About one-third (32%) of Medicare-covered American Indians and Alaska Natives are under age 65, qualifying for Medicare because of a permanent disability—double the proportion found in the overall Medicare population. About 200,000 American Indians and Alaska Natives under the age of 65 have Medicare because of a disability (for which they receive Social Security Disability Insurance benefits) or other qualifying health condition. The rate of people under age 65 enrolled in Medicare is similar for American Indians as it is for the general population (4% and 3% respectively). However, the share of American Indian and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries who are under age 65 is twice that found in the overall Medicare population (32% vs. 16%) (Figure 7). Therefore, the relatively larger proportion of American Indians and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries who are under age 65 is likely related to shorter life expectancies, as described earlier in this brief.

Figure 7: About one-third of American Indians and Alaska Natives enrolled in Medicare are under age 65

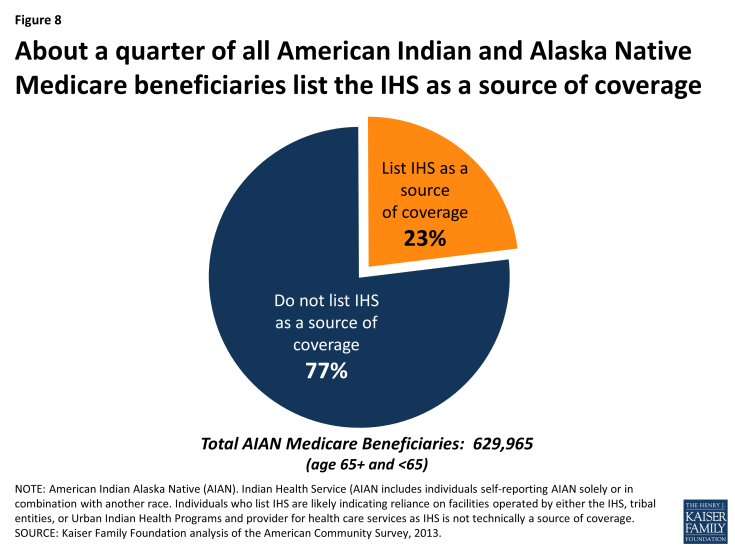

About a quarter (23%) of American Indian and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries list IHS as a “source of health coverage” (Figure 8). Although IHS is not technically a source of coverage, but rather a health care service delivery system for eligible American Indians and Alaska Natives, individuals who report having IHS coverage are likely indicating that they rely to some degree on I/T/Us for health care services. This equates to about 145,000 American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries. Other research using Medicare claims data estimates about 200,000 Medicare beneficiaries using IHS services (text box 2).

Figure 8: About a quarter of all American Indian and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries list the IHS as a source of coverage

The remaining three quarters (77%) of American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries who do not list IHS as a source of coverage, may not live on or near reservations or may not qualify for IHS services (or perhaps may not consider IHS a source of coverage, and thus did not list it). Looking only at elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives who have Medicare, rates of reporting IHS coverage are a little higher for those with no supplemental insurance (28%), and a little lower (19%) for those with private or military coverage (not shown).

Other surveys also find that the majority of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives have Medicare, but at lower rates than estimated by the ACS. Analysis of other surveys suggests a possible lower bound for estimating Medicare coverage rates among American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and older. For example, the Survey of Elders finds a Medicare coverage rate, for those ages 65 and older, of 78 percent. While this survey has a large sample of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives (9,488) and is conducted by trained tribal members, it is not weighted to be nationally representative. Another survey, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), finds a Medicare coverage rate of 88 percent among American Indians age 65 and older. While this survey is nationally representative, it has a small sample of elderly American Indian and Alaska Natives (146) which compromises the reliability of its findings.

Federal reports have documented barriers that American Indians and Alaska Natives face in enrolling in Medicare (above and beyond those experienced generally by low-income populations). These issues, as well as methodological issues with race identification, and variation in interviewing techniques, suggest that the percent of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives without Medicare coverage could range from 22 percent (Survey of Elders) to 4 percent (ACS). Nonetheless, all three surveys—the ACS, the NHIS, and the Survey of Elders—find that Medicare is the most frequently reported source of health care coverage among American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and over. Without Medicare, American Indians and Alaska Natives could face significant barriers to care, unless they received all services from an I/T/U or under referral through the PRC program.

SECTION 3: The Intersection between the IHS and Medicare in access and coverage for American Indians and Alaska Natives

American Indians and Alaska Natives who are enrolled in Medicare may receive services from providers and facilities that are either affiliated or unaffiliated with IHS. When beneficiaries receive health care or prescription drugs from facilities operated by IHS, tribal entities, or the Urban Indian Health Program, they are not charged any cost-sharing, in general. However, when they receive care from non-IHS-funded providers, beneficiaries may incur cost sharing (including deductibles, coinsurance and copayments), depending on the service and whether they have supplemental coverage. When seeking care outside of the IHS system, American Indian and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries may be able to obtain assistance from their Tribes for cost sharing responsibilities, if they do not have the ability to pay on their own.

As described earlier, most services provided at I/T/Us are for primary care, common specialty services and pharmacy services. For other services, including hospital care, high-technology outpatient procedures, and post-acute care services, American Indians and Alaska Natives who are Medicare beneficiaries may need to go to IHS contracted providers through the Purchased/Referred Care (PRC) program or to providers outside the IHS system. In general, however, access to services through the PRC Program is limited to only high-priority, emergent cases.

Reimbursements from third-party insurers, including Medicare, are important revenue sources for IHS facilities, in light of IHS funding constraints.33 As the payer of last resort, IHS facilities are expected to collect reimbursements for services from patients’ third-party payers, including Medicare. In the aggregate, IHS facilities will collect an estimated $217 million in reimbursements from Medicare for services they provide to Medicare beneficiaries in 2014. While Medicare payments make up a relatively small share of facilities’ operating budgets, these reimbursements are not insignificant, given the fiscal pressures inherent in IHS’s overall funding. When caring for Medicare patients who have no supplemental coverage, IHS facilities receive Medicare’s full payment for the service, but forego the portion that would otherwise be attributable to beneficiary cost-sharing, such as the 20-percent co-insurance for physician services. In contrast, IHS facilities may seek payment for cost-sharing from patients’ supplemental insurers when applicable, including Medicaid, the Medicare Savings Programs, the Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program, VA coverage, or private supplemental insurers, including health plans in the Medicare Advantage program. Similarly, when American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries have Medicare prescription drug coverage, I/T/Us may seek reimbursement for applicable costs from beneficiaries’ Part D plans.34

To qualify for Medicare reimbursement, I/T/Us must meet Medicare’s conditions of participation. Medicare payments collected by the IHS- and tribally-operated facilities stay with those facilities and supplement other IHS funds, grants and other sources of funding.35 IHS may not offset its funding to provider facilities based on each facility’s ability to collect from third-party payers, such as Medicare.36

Providers who contract with IHS to provide services to American Indians and Alaska Natives through the PRC program follow the same reimbursement rules as the IHS facilities. That is, when providing services to American Indians and Alaska Natives that are authorized by IHS as emergent and/or high-priority, PRC providers may not seek any reimbursement from their patients, including from those with Medicare, but may seek cost-sharing reimbursement from supplemental insurers, when applicable. Also, hospitals (but not physicians and other facilities) that treat American Indian and Alaska Native patients under contract with IHS may not charge higher-than Medicare rates for their services, regardless of the patient’s type of insurance. This payment policy helps stretch IHS resources since its liability is capped at Medicare rates. Recently, the IHS released a proposed rule that would extend this rate cap to apply to all physicians, health care professionals and non-hospital-based services.37

Funding constraints limit patient access to PRC services to only high-priority, acute, urgent and emergent cases.38 Although the PRC program is designed to expand the availability of non-primary care IHS providers—such as specialty consultations, rehabilitation care, skilled nursing facility and home health services—in reality, access to PRC providers is limited to those with the greatest medical urgency. For example, the IHS reports that in FY 2013, 77 percent of IHS-operated PRC programs were only able to purchase the first priority (most emergent) level of services. In the same year, the PRC denied about $761 million for an estimated 147,000 services needed by eligible American Indians and Alaska Natives. Consequently, in many cases, American Indians and Alaska Natives might need to seek services outside of the IHS system where, if they have Medicare and do not have a PRC referral, are subject to cost-sharing requirements, as are all beneficiaries. When PRC providers furnish care that is not authorized by IHS as high-priority, then they are acting as any other non-IHS funded provider and may, therefore, charge their American Indians and Alaska Natives patients for applicable out-of-pocket expenses.

Potential barriers to enrollment in Medicare and Medicare Savings Programs and Implications for the Indian Health Service

Elderly and disabled American Indians and Alaska Natives face potential factors that may deter enrollment in Medicare and Medicare Savings Programs, which has implications for beneficiaries themselves and for the Indian Health Service. Although data limitations make it difficult to quantify the extent to which eligible American Indians and Alaska Natives are not enrolled in Medicare, federal reports, researchers, and advocacy organizations have cited numerous potential factors that may deter enrollment in Medicare and Medicare Savings Programs.39 In some cases, the Tribal leaders and members may perceive that the Federal Trust responsibility to provide health care to the Tribes means that their members do not need to apply for assistance from federal programs.40 Also, the Tribes or their members may not be aware of programs for which they are eligible, including the Medicare Savings Programs or the Part D Low Income Subsidy Program, because they assume they are required to obtain all of their medical services through the IHS or Urban Indian Health facilities.

This misunderstanding and lack of knowledge about Medicare programs may be due to a number of factors. Effective outreach to American Indians and Alaska Natives has historically been very challenging and, based on research from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) about the outreach experience related to the ACA, requires a “large, multipronged effort, including use of media, direct mail, one-on-one counseling and partnerships with community organizations.”41 To reach the remaining American Indians and Alaska Natives who are eligible and not enrolled or enrolled and not taking advantage of their Medicare status may require a significant investment of IHS resources.

Another area of confusion is the age of eligibility for Medicare. For many tribes, people may be considered “elders” when they are younger than 65. In fact, the IHS defines elder at age 55 compared to more closely match elder-status among American Indian and Alaska Native populations. This contrasts with Medicare, for which eligibility for of non-disabled people starts at age 65. Consequently, American Indians and Alaska Natives may be considered “elders” in their community, but if they try to enroll in Medicare, learn that they are not eligible.42

Other potential factors affecting enrollment are not unique to American Indian and Alaska Native populations, but rather apply to low-income and vulnerable populations more broadly. Communities with high rates of poverty and/or lower education levels have historically faced problems enrolling in federal programs, particularly in rural and some inner city areas. As identified in research and other federal reports, these factors include: complexity of enrolling in financial assistance programs, such as Medicaid, Medicare Saving Programs and the Part D Low Income Subsidy Program; lack of awareness of these programs; transportation barriers (many reservations, for example, lack any form of public transportation, which creates a particular challenge for many elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives who are without cars or are unable to drive them); language (many American Indian and Alaska Natives languages are spoken only, limiting the use of written outreach materials); and low literacy and cultural barriers. The remote rural location of many American Indian and Alaska Natives adds to the difficulties of outreach, education and enrollment assistance. For some American Indians and Alaska Natives, the lack of a permanent address is a major barrier to obtaining care and the necessary financial supports.43

SECTION 4: Future Opportunities and Challenges

While the majority of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives have Medicare coverage, cost and access challenges remain a concern for this population, particularly among the relatively large share with no supplemental coverage and no access to I/T/Us. These concerns stem from the significant health needs and relatively low incomes of elderly and disabled American Indians and Alaska Natives. Also, these circumstances may be further exacerbated by barriers that they and other disadvantaged populations face when enrolling in programs that provide assistance with out-of-pocket costs, such as Medicaid, Medicare Savings Programs, and low-income subsidy assistance in Part D. American Indians and Alaska Natives with access to clinics and providers that are funded through the IHS have no cost-sharing, but services at these clinics are typically limited to primary care. Further, the IHS is subject to appropriations and thus competes with other programs for federal funding. As a result, constraints on available funding will continue for the foreseeable future.

Data limitations continue to compromise a better understanding of the health and coverage needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives who are age 65 and older or living with long-term disabilities. Several factors make it difficult to determine the precise number of American Indians and Alaska Natives who are eligible for Medicare and who are enrolled in Medicare. These factors include differences in definitions used to identify and categorize individuals as American Indian or Alaska Native, differences in survey methodologies, and longstanding inaccuracies in Medicare’s administrative data regarding beneficiary race and ethnicity. Researchers and advocacy organizations, such as the California Rural Indian Health Board (CRIHB), have called for more attention to race and ethnicity, including establishing the platform for beneficiaries to self-identify race and ethnicity at the time of enrollment in Medicare.

Looking ahead, some opportunities may exist for Medicare to improve access to care among American Indian and Alaska Native Medicare beneficiaries. Ongoing Medicare initiatives to improve population health in rural communities, for instance, could provide American Indians and Alaska Native beneficiaries with access to more coordinated and integrated care. For example, the Frontier Community Health Integration Project—a demonstration project being implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in five states (Alaska, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, and Wyoming), all of which have relatively higher concentrations of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives. The purpose of this demonstration is to develop and test ways to coordinate the delivery of acute care, extended care, and other essential health care services to Medicare beneficiaries living in sparsely populated areas. Other Medicare demonstrations run through the CMS Innovation Center include initiatives to focus on providing culturally competent care through advanced primary care models, such as medical homes. This work may lead to greater emphasis on understanding communication differences and health needs that are unique to American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

Opportunities also exist within the IHS. For example, IHS has proposed regulations to stretch the limited dollars available for the PRC program by capping (at Medicare payment rates) the amount that contracted providers may charge for serving any eligible American Indian and Alaska Native patient. IHS facilities and I/T/U pharmacies may also gain additional Medicare reimbursements in future years as the number of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives increases. Similarly, broad coverage expansions under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which provide new coverage pathways (through Marketplaces and Medicaid), could increase IHS providers’ access to third-party reimbursements, thereby increasing their operating revenues and enhancing their capacity to provide services to all their patients—including those who are elderly and living with long-term disabilities.

More broadly, the ACA includes other provisions which could improve the health of American Indians and Alaska Natives as they age into Medicare. The ACA permanently reauthorizes the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, which includes provisions designed to: increase the number of providers who serve American Indians and Alaska Natives; increase and improve health promotion and disease prevention services; enhance access to care for urban American Indians and Alaska Natives; and modernize facilities where American Indians and Alaska Natives receive care. Other broad provisions within the ACA that aim to reduce disparities in health and access to care among disadvantaged populations could have important implications for American Indians and Alaska Natives, including: increased funding for community health centers; workforce development and diversity initiatives; improvements in data collection by race and ethnicity; and prevention, wellness, and public health initiatives.

Technical support in preparation of this report was provided by Health Policy Alternatives, Inc. Anthony Damico, an independent consultant, provided programming and statistical support. This report was funded in part by AARP.

Box 1: Selected Population and Health Surveys: Estimating Results for American Indians and Alaska NativesAmerican Community Survey (ACS) The ACS is a national survey of approximately 3.5 million households conducted annually by the United States Census Bureau. It focuses on age, sex, race, family and relationships, income and benefits, health insurance, education, veteran status, employment, housing, and transportation. Its primary mode of data collection is through the mail with paper questionnaires. For 2013, the ACS includes a sample size of 62,316 American Indians and Alaska Natives, of whom 6,531 are age 65 and over. Advantages and limitations: By design, the ACS’s relatively large sample size enables it to produce community-level estimates (both by race and ethnicity, and geographic area). The mail-based collection method does not allow respondents to ask clarifying questions while completing the survey. The survey asks only one question regarding health insurance status. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) The BRFSS is a continuous telephone health survey, interviewing more than 500,000 adults in 2013. It collects data on health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventative services. The BRFSS has a set of core questions asked nationally of all respondents, as well as some questions that are state-specific. For 2013, BRFSS includes a sample size of 7,789 American Indians and Alaska Native adults, of whom 1,762 are age 65 and over. Advantages and limitations: For a telephone survey, BRFSS has a relatively large sample size and respondents are able to speak to trained, individual interviewers. BRFSS questions on health status and behaviors are comprehensive, but insurance coverage results do not distinguish by type of insurance. Identifying Our Needs: A Survey of Elders The Survey of Elders is funded through the Administration on Community Living in the Department of Health and Human Services, and is administered by the National Resource Center on Native American Aging. The survey is fielded in three-year cycles and collects information from Native Americans age 55 and older on general health status, health care and screenings, activities of daily living, tobacco and alcohol usage, weight and nutrition, social support/housing, demographics and social functioning. Trained tribal members often conduct the surveys. Cycle V, released in 2013 includes a sample size of 9,488 American Indians and Alaska Natives age 65 and over. Advantages and limitations: The Survey of Elders has a large sample of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives and is conducted by people who are either tribal members or familiar with the tribal population, addressing cultural issues that may affect responses in other surveys. Although a sampling frame guides data collection, the survey results are not weighted to be nationally representative. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) The NHIS is a national, face-to-face household survey administered annually by the National Center for Health Statistics to 35,000 households (approximately 87,500 persons) each year. It provides health status, health care access, and health service utilization information, collected through personal household interviews conducted by individuals trained about health insurance information. For 2013, the NHIS includes a sample size of 1,455 American Indians and Alaska Native adults, of whom 146 are age 65 and over. Advantages and limitations: The NHIS provides relatively detailed health insurance information and uses interviewers who have received training on the concepts included in the survey, such as health insurance. The small sample of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives limits the reliability of results for this population. |

Box 2: Using Medicare Claims Data for Analysis of American Indian and Alaska Native BeneficiariesSome researchers have used Medicare administrative and claims data to analyze Medicare enrollment and service use among beneficiaries who are American Indian and Alaska Native, but most acknowledge significant and long-standing inaccuracies in the racial and ethnic identification of these individuals in the Medicare data.44 Research that uses Medicare claims and administrative data to identify beneficiaries who are American Indians or Alaska Natives, typically categorize beneficiaries as American Indian and Alaska Native if they fulfil one of the following three circumstances: 1) live in an IHS service delivery area, 2) have received a Medicare covered service from an IHS facility, or 3) are listed or self-reported in Medicare’s administrative files as American Indian or Alaska Native and living outside an IHS area. Using these criteria, researchers identified 220,000 beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare in 2010—of which 87 percent are identified through the first two criteria and 13 percent are living outside an IHS area and are identified as American Indian or Alaska Native in Medicare files.45 This low count strongly suggests that relying on Medicare data alone to determine Medicare enrollment among American Indians and Alaska Natives is problematic because it is appears to undercount the number enrolled in Medicare. Despite the potential shortcomings of the Medicare data, it presents some findings that are consistent with other survey data. For example, analysis by the California Rural Indian Health Board shows a higher proportion of American Indians and Alaska Natives in Medicare are under age 65, compared with the overall beneficiary population. Specifically, among all Medicare beneficiaries in 2009, 29 percent of those using IHS were under 65 and 43 percent of self-declared American Indians and Alaska Native who do not use IHS were under 65.46 Additionally, this claims analysis shows a higher proportion of American Indian or Alaska Native beneficiaries qualify for Medicare because they have end-stage-renal disease and 22 percent of beneficiaries accessing IHS were also enrolled in Medicaid. Medicare’s administrative data provides some ability to examine American Indian and Alaska Native beneficiaries’ enrollment in supplemental coverage that may assist in out-of pocket expenses, such as MSPs, Medicare Advantage plans or separate drug plans. This research finds that 2009 Part B premiums were paid by an MSP program for about 31 percent of people accessing IHS and 43 percent of self-declared American Indians and Alaska Natives not accessing IHS.47 Claims analysis also shows lower proportions of American Indians and Alaska Natives enrolled in Medicare Advantage, compared with the overall Medicare population. This difference is likely associated with geographic variation in the prevalence of Medicare Advantage plans, with fewer plans offered in rural areas, particularly those associated with Indian reservations.48 Finally, for 2010, 37 percent of IHS-American Indians and Alaska Natives in traditional Medicare had Part D coverage; of them, about 22 percent were eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare (i.e. were full duals) thus qualifying for the Low Income Subsidy that helped pay their Part D premiums.49 |