Health Coverage and Care in the South in 2014 and Beyond

Translating Coverage to Care: Delivery Systems and the Safety Net

To improve health outcomes in the long term, it will also be important to ensure that newly-insured individuals are able to obtain needed primary and specialty care services. As uninsured individuals in the South gradually gain coverage and seek care, health resources in these communities may be further stretched. The ACA includes a number of provisions to help states improve health system capacity, including increased funding to expand community health centers and a temporary increase in Medicaid payment rates for primary care physicians.1 Increases in physician capacity will be especially important in areas with historically limited health resources.

Provider Capacity in the South

Many Southerners live in a primary care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA), meaning that they reside in a region with a documented shortage of primary care providers. As of 2012, nearly one-quarter (22%) of southern residents were residing in a primary care HPSA. In four southern states (AL, DC, LA, and MS), more than one in three residents lived in a primary care HPSA, and in Mississippi, over half of the state population lived in a primary care HPSA—the highest share in the country (Table 4). As coverage expands and the demand for care increases, expanding provider capacity will be key to ensuring that coverage translates into access to care.

| Table 4: Share of Population Living in a Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA), by State, 2014 | ||

| State | Number of Residents Living in Primary Care HPSA | Share of Population in HPSA |

| United States | 57,742,576 | 18% |

| South | 25,759,887 | 22% |

| Mississippi | 1,676,661 | 56% |

| Louisiana | 2,001,796 | 43% |

| Alabama | 1,802,365 | 37% |

| District of Columbia | 241,638 | 37% |

| Oklahoma | 1,113,275 | 29% |

| South Carolina | 1,286,623 | 27% |

| Florida | 4,613,535 | 24% |

| Delaware | 203,525 | 22% |

| Georgia | 1,984,945 | 20% |

| Texas | 5,229,179 | 20% |

| Kentucky | 763,738 | 17% |

| Maryland | 931,622 | 16% |

| Tennessee | 965,306 | 15% |

| West Virginia | 284,335 | 15% |

| Virginia | 1,144,027 | 14% |

| Arkansas | 364,909 | 12% |

| North Carolina | 1,152,408 | 12% |

| SOURCE: Bureau of Clinician Recruitment and Service. Health Resources and Services Administration. “Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas.” January 1, 2014 | ||

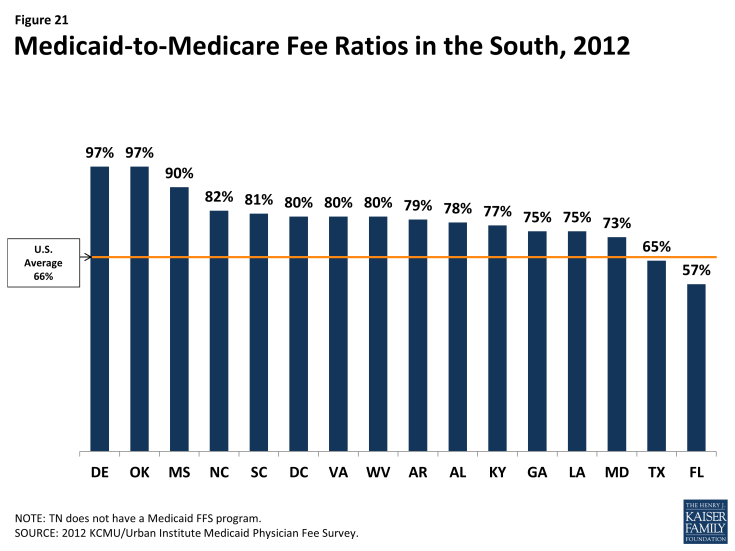

Medicaid payment rates are one lever for increasing provider supply and access in the program, but additional measures are needed to overcome provider shortages. In 2012, state Medicaid programs overall paid physicians just 66% of Medicare fee levels. Notably, though, 13 of the 17 Southern states paid Medicaid rates equal to at least 75% of Medicare rates, including eight southern states that paid 80% or more of Medicare fee levels (Figure 21). Under the ACA, Medicaid payment rates to primary care physicians (PCP) for most of their services must be at least equal to Medicare rates in 2013 and 2014 (the difference is fully funded by the federal government); in 2013, this provision increased PCP fees by at least 40% in half of the southern states, including Florida, where they more than doubled.

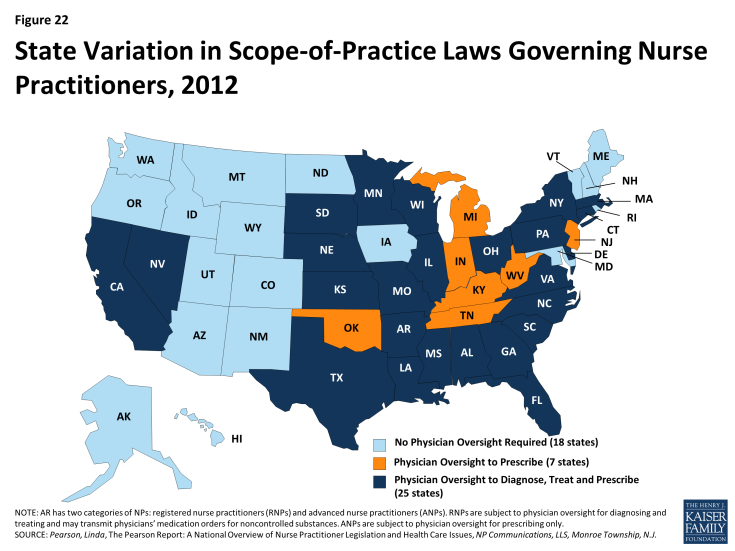

Although paying providers fee-for-service rates closer to Medicare and private insurance rates may attract more provider participation in Medicaid, absolute shortages in the supply of physicians, particularly in rural and low-income communities, are system-level capacity constraints that Medicaid payment rates cannot correct. Broader strategies and investments to develop a more adequate health care workforce are called for. The ACA includes numerous provisions along those lines, but they will take time to bear fruit. A more immediate strategy for expanding access (especially access to primary care) is to expand the role of nurse practitioners (NP), physician assistants (PA), and other health professionals in delivering care. A large body of evidence on NPs shows that the care they provide is of equal or, in some cases, better quality than physician-provided care for the same conditions. In many states, including 11 states in the South, state regulations that restrict NP scope of practice are a major obstacle to this strategy. These restrictions prevent NPs from diagnosing and treating illness and prescribing drugs without physician supervision.2 Of the southern states, only DC, Maryland, and Delaware extend full autonomy to NPs to practice independently at the “top of their license” (Figure 22).

Medicaid managed care programs can also expand the role of NPs by including them in their primary care provider panels. A 2009 RAND study that estimated potential health care savings associated with expanding the role of NPs and PAs in Massachusetts assumed in its model that NPs and PAs could provide care for six simple acute conditions (e.g., cough, fever, earache) that are among those commonly treated at retail clinics staffed by these providers. Care for these six conditions, plus well-baby visits and general medical examinations, which the model also assumed NPs and PAs could provide, represent nearly one in five of all office-visits nationally.3 This analysis suggests that expanding the use of NPs and PAs in the South – in effect, increasing the supply could increase the availability of routine primary care.

Medicaid managed care

Nationwide, a large and growing share of Medicaid beneficiaries receive their care in capitated managed care plans. Increasingly, state Medicaid programs across the country are contracting with private managed care plans to deliver Medicaid benefits to Medicaid enrollees. Under these contracts, states pay a fixed “capitation” rate to plans for each person enrolled, and the plans are at financial risk for all the services specified in their Medicaid contracts. Enrolled beneficiaries receive all or most of their care from their plan’s network of providers. Under the other major (though much smaller) model of Medicaid managed care, known as primary care case management (PCCM), states retain fee-for-service payment, but provide a small monthly fee to primary care providers to coordinate primary care for their Medicaid patients. Some states’ PCCM programs involve partial capitation payment.As of July 2011, over half of all Medicaid beneficiaries nationally were enrolled in risk-based managed care, but the proportion varied considerably across the country. A number of factors may contribute to the variation. Some states or areas lack sufficient population to attract risk-based plans. Organized medicine and managed care interests may influence Medicaid policy choices. Some states have abandoned risk-based contracting because of plan exits from the market, budget pressures, or a preference for managing their Medicaid programs themselves by contracting directly with providers, rather than shifting responsibility and financing for services to insurers.

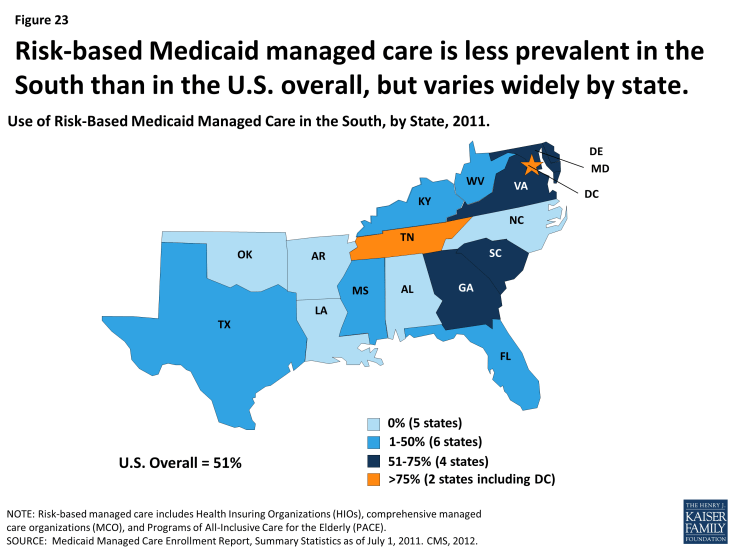

Most states in the South have some share of their Medicaid population enrolled in risk-based managed care. In 2011, 5 of the 17 states in the South had no risk-based Medicaid managed care (Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Oklahoma). However, the other 12 had risk-based programs that, with a few exceptions, covered at least half their Medicaid population, and substantially more in the District of Columbia (77%), Maryland (75%) and Tennessee (97%) (Figure 23). Notably, Louisiana more recently adopted risk-based managed care statewide, Alabama is slated to do so later this year, and under Arkansas’ proposed “private option” for implementing the ACA Medicaid expansion, adults newly eligible for Medicaid are to be enrolled in the same managed care plans offered in the new insurance Marketplaces.

Figure 23: Risk-based Medicaid managed care is less prevalent in the South than in the U.S. overall, but varies widely by state

PCCM programs are prevalent in the South as well, operating in 12 of the 17 states in the region. In four states – Arkansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Oklahoma – over 60% of Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in these arrangements as of 2011. Interestingly, while the Medicaid trend nationally is for states to move away from the fee-for-service toward risk-based managed care, in the mid-2000s, both North Carolina and Oklahoma terminated their risk-contracting programs and implemented PCCM statewide.

Trends suggest a continued movement toward managed care within the South going forward. In a recent 50-state survey, nearly all states in the South reported that they undertook Medicaid managed care initiatives in 2013 or planned to in 2014, including expansions of managed care to new geographic areas or groups, mandatory managed care enrollment, implementation or expansion of managed long-term care, and measures to improve quality.

Delivery system innovation

State Medicaid programs, including many in the South, are in a period of dynamic innovation in health care delivery and payment. Medicaid programs have historically been a source of new approaches to improving care for some of the nation’s most medically complex and low-income populations. Now, new options, demonstration programs, and funding opportunities provided by the ACA are catalyzing increased activity, including Medicaid participation in multi-payer initiatives designed to leverage broader systemic change, as well as reforms within Medicaid programs themselves.

Consistent with a broader trend nationally, most states in the South have undertaken medical home initiatives designed to provide comprehensive and continuous patient-centered care to Medicaid beneficiaries. In addition, both Alabama and North Carolina have taken up a new Medicaid option under the ACA to establish health homes to provide comprehensive care coordination for Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic conditions, and Arkansas, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maryland, Oklahoma, and West Virginia are planning such programs. Alabama and North Carolina have also taken steps to establish accountable care organizations (ACO) in Medicaid. In ACOs, participating providers, plans, and hospitals are collectively responsible for the care of a defined population, encompassing the continuum of care across different settings. The participating providers agree to achieve specified financial and quality outcomes and may share in savings associated with their performance. The following selected initiatives in Arkansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas illustrate the diversity of service delivery and payment innovation underway in Medicaid:

| Box 2: Examples of Innovative Delivery System and Payment Models in the South |

|

Arkansas. The State Innovation Models (SIM) initiative, sponsored by CMS’ Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, provides support to states for the development and testing of state-based models for multi-payer payment and health care delivery system transformation, with the goal of improving health system performance. Arkansas was one of six states to receive a Model Testing award under the initiative, and will receive up to $42 million over 42 months to implement its plan.

.

Arkansas’ innovation plan is aimed at moving from an encounter-based, fee-for-service system to a more patient-centered, comprehensive, and coordinated care system. Within three to five years, most Arkansans will have access to medical homes, and those with more complex needs (e.g., individuals with developmental disabilities and behavioral health conditions) will have access to health homes. Both medical and health homes will receive episode-based payments for certain procedures, acute care, and chronic care for selected conditions. Medical homes will extra fees for care coordination, and may share in savings based on their performance. Health homes will also receive such fees, with shared savings possible in the future. The plan calls for Medicaid, CHIP, Medicare, and private payers to participate in the initiative. Arkansas has already established common payment mechanisms for Medicaid and private payers, consistent quality metrics, and a multi-payer provider web portal. The plan also includes strategies to strengthen the health care workforce, use team-based care, increase consumer engagement, and adopt electronic medical records and a health information exchange. The state projects savings of $1.1 billion over the three-year Model Testing period, and $8.9 billion through 2020.

.

North Carolina. Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC), North Carolina’s widely recognized statewide Medicaid medical home and care management program, serves the vast majority of Medicaid beneficiaries in the state. Beneficiaries are enrolled in participating primary care or group practices that serve as medical homes in their local communities. The state funds and provides training, data, and tools to 14 regional Community Care networks that support the practices and work with them to improve care.

.

North Carolina has built on the CCNC infrastructure over time to enhance the delivery system in the state. In 2008, for example, North Carolina initiated the Transitional Care Program (TCP) after it expanded CCNC to include aged and disabled Medicaid beneficiaries. These beneficiaries have high rates of multiple chronic conditions and are thus at high risk for fragmented care that can lead to multiple hospitalizations. The TCP identifies high-risk CCNC members when they are admitted to the hospital and plans for, coordinates, and arranges their transition from the hospital back to the community. The concept is that robust discharge and transition planning can reduce the risk of emergency department use and hospital readmission for complex Medicaid patients, improve health outcomes, and reduce costs. A recent evaluation of the TCP showed that readmission rates among Medicaid beneficiaries who received TCP support were 20% lower than the rates for clinically similar patients who received usual care. TCP participants were also less likely to experience multiple readmissions.

.

South Carolina. Medicaid pays for 50% of all births in South Carolina. The South Carolina Birth Outcomes Initiative (BOI), a multi-stakeholder effort that includes the South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, the state hospital association, the state chapter of the March of Dimes, and BlueCross Blue Shield of South Carolina (the other major payer of births in the state), has three major goals: to improve health outcomes for newborns in the Medicaid program and throughout the state, decrease the number of days babies spend in neonatal intensive care units (NICU), and reduce racial disparities in birth outcomes.

.

The BOI comprises several components. One is Medicaid reimbursement for Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) services, to help identify and treat pregnant and postpartum Medicaid beneficiaries who may smoke, have alcohol or other substance dependencies, experience depression, or face domestic violence. The BOI also involves efforts to encourage breastfeeding, including incentives to hospitals to improve their support for breastfeeding and achieve “Baby Friendly Hospital” status. Reducing early elective deliveries in the state is another major thrust of the BOI. An initial voluntary effort by the state’s birthing hospitals led to a 50% reduction in early elective deliveries. To gain more ground, the Medicaid program and BlueCross BlueShield jointly pursued a policy of non-payment for early elective inductions. Data from the first eight quarters show large declines in the early elective rate in Medicaid and across all payers and declines in NICU admissions also occurred. A report prepared for the state showed savings of $6 million in the first quarter of 2013.

.

Texas. Faced with rising health care costs and disparities in health outcomes, policymakers have increasingly focused on the benefits of investing in preventive care. In particular, states are expanding efforts to promote personal responsibility and support individuals in changing their lifestyle habits to achieve better health. To build on these efforts, the ACA established the Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) program, which provides a total of $85 million in grants over five years to states that provide incentives to Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in prevention programs and change their health risks and outcomes by adopting healthy behaviors. Each program must address at least one of the following prevention goals: tobacco cessation, weight loss, lowered cholesterol, lowered blood pressure, and prevention or management of diabetes.

.

Texas, one of ten states to receive an award, began implementing its Wellness Incentives and Navigation (WIN) Project in April 2012. The project targets 1,250 nonelderly adults in Harris County with both a behavioral health condition (including mental health and substance abuse disorders, as well as severe mental illness) and a physical chronic health diagnosis. Structured as a randomized control trial, the project randomly assigns volunteer participants to either an intervention or a control group. Individuals in the intervention group develop individual wellness plans and have access to flexible wellness accounts of $1,150/year to help pay for services and activities that advance their specific health goals. They also receive support from trained health system navigators to manage their health and wellness plans more effectively. The program is available for a maximum of three years for each participant, with the last participants completing the study in December 2015. The most popular goals for participants thus far have been weight loss, increased physical activity, and healthy eating habits.

|

The Safety Net

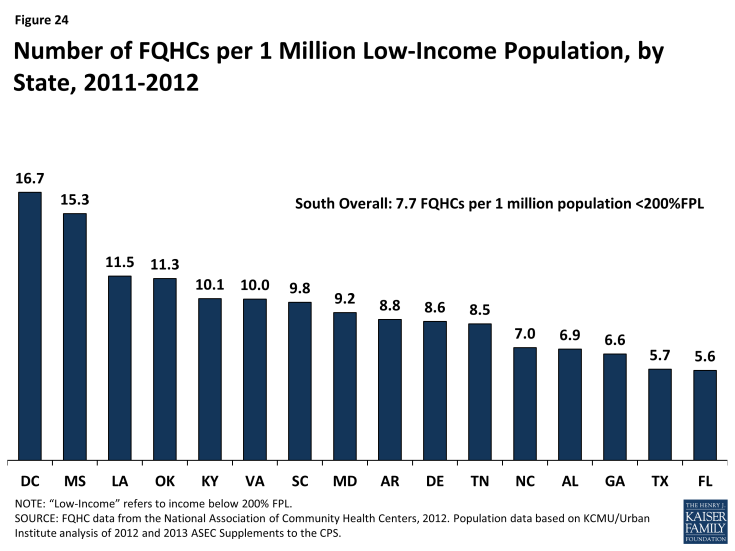

Safety net providers will continue to be an important part of the health care system in the South. Historically, uninsured and low-income individuals have relied on safety net providers such as community health centers and clinics when seeking care, and even with broad-scale efforts to expand physician capacity and improve the delivery of services to low-income populations, these providers will likely remain a primary source of care for millions of newly-insured Southerners and many low-income individuals who will likely remain uninsured. As of 2011, there were 388 federally-funded federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in the South that served over six million patients.4 The number of FQHCs available to serve the low-income population in the South varies by state from 5.6 per million low-income people in Florida to nearly 17 FQHCs per million people with low incomes residing in Mississippi (Figure 24). In addition, as of 2011, there were over 1,500 Medicare-certified rural clinics in the South serving the 20 million Southerners residing in rural areas5 and 448 public hospitals, which saw nearly 2.5 million patient visits in the year.6

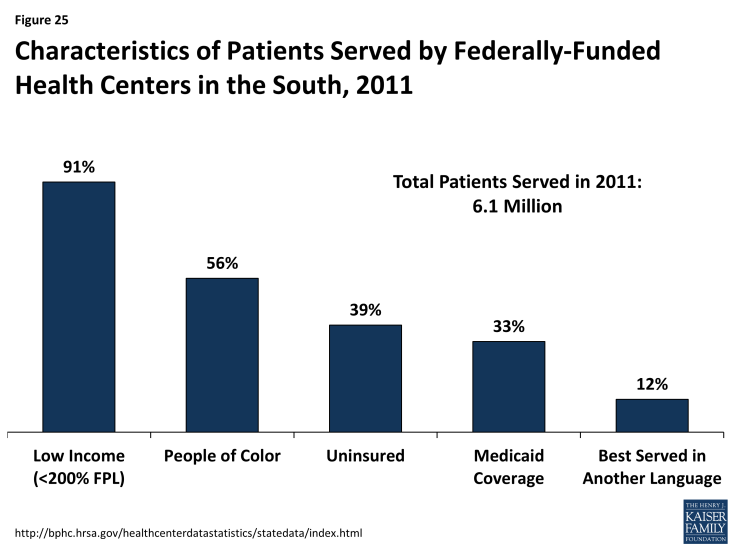

Community health centers and other safety net providers serve many vulnerable populations in the South. In addition to providing free or low-cost services to those with low incomes, community health centers are often seen as a trusted source for care within the community and are able to offer culturally and linguistically appropriate services that meet the needs of the diverse populations they serve. In the South, over 90% of patients in federally-funded community health centers are low-income. Over half (56%) are people of color, nearly four in ten are uninsured, 12% are better served in a language other than English, and 5% are homeless (Figure 25). Health centers provide an array of services to their patients, including primary and preventive care, professional services such as dental and mental health care, and enabling services such as case management, health education, and interpretation and translation services.7 As coverage expands, some of these health centers may experience revenue gains as more patients obtain coverage. However, they will continue to serve as a key source of care for individuals who remain uninsured or who have historically relied on their services, requiring adequate resources to support this role.