2013 Employer Health Benefits Survey

Published:

Abstract

The 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey was released September 10, 2014.

This annual survey of employers provides a detailed look at trends in employer-sponsored health coverage, including premiums, employee contributions, cost-sharing provisions, and other relevant information. The 2013 survey included almost three thousand interviews with non-federal public and private firms.

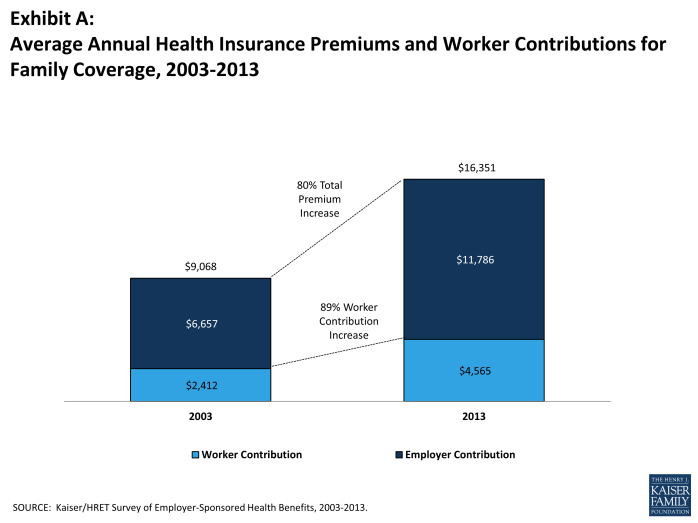

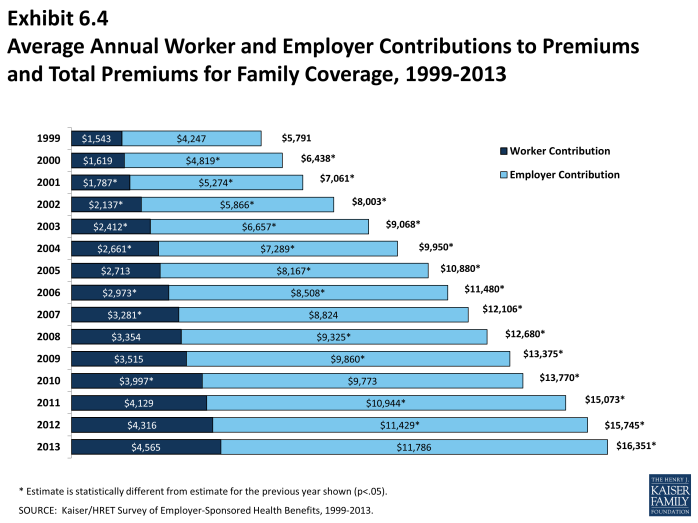

Annual premiums for employer-sponsored family health coverage reached $16,351 this year, up 4 percent from last year, with workers on average paying $4,565 towards the cost of their coverage, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) 2013 Employer Health Benefits Survey.

News Release

- A news release announcing the publication of the 2013 Employer Health Benefits Survey is available here.

Summary of Findings

- The Summary of Findings provides an overview of the 2013 survey results and is available under the “Summary of Findings” tab or as a pdf file in the “Download” box to the right.

Full Report

- The complete Employer Health Benefits Survey Report includes over 200 exhibits and is available under the “Report” tab or as a pdf file in the “Download” box to the right. The “Report” tab contains 14 separate sections. Users can also download each section separately from the “Download” box or download the complete set of section exhibits from the bottom of the respective section page.

Health Affairs

- The peer-reviewed journal Health Affairs has published an article with key findings from the 2013 survey: Health Benefits in 2013: Moderate Premium Increases in Employer-Sponsored Plans.

Interactive Graphic

- This graphing tool allows users to look at changes in premiums and worker contributions for covered workers at different types of firms, over time.: Premiums and Worker Contributions Among Workers Covered by Employer-Sponsored Coverage, 1999-2013.

Key Exhibits – Chartpack

- Twenty overview slides from the 2013 Employer Health Benefits Survey are available as a slideshow or as pdf.

Additional Resources

- Standard errors for selected estimates are available in the Technical Supplement here.

- Employer Health Benefits Surveys from 1998-2012 are available here. Please note that historic survey reports have not been revised with methodological changes.

- Researchers may request a public use dataset here.

Researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation, NORC at the University of Chicago, and Health Research & Educational Trust designed and analyzed the survey.

Summary of Findings

2013 Summary of Findings

Employer-sponsored insurance covers about 149 million nonelderly people.1 To provide current information about employer-sponsored health benefits, the Kaiser Family Foundation (Kaiser) and the Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) conduct an annual survey of nonfederal private and public employers with three or more workers. This is the fifteenth Kaiser/HRET survey and reflects employer sponsored health benefits in 2013.

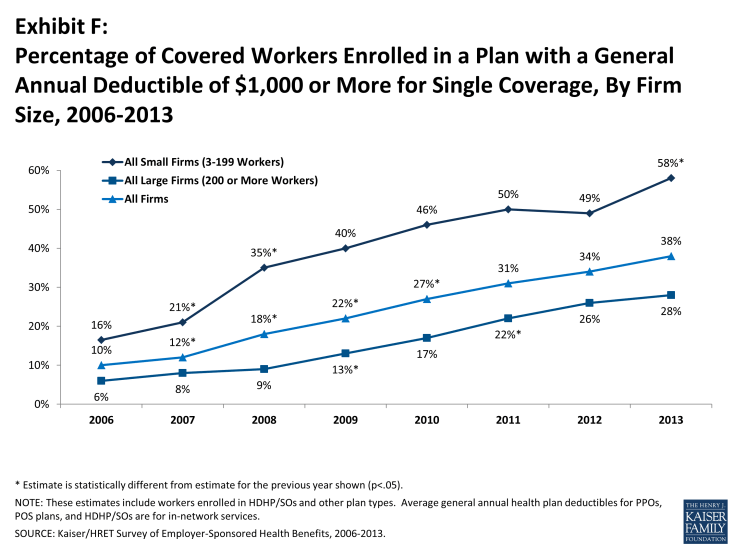

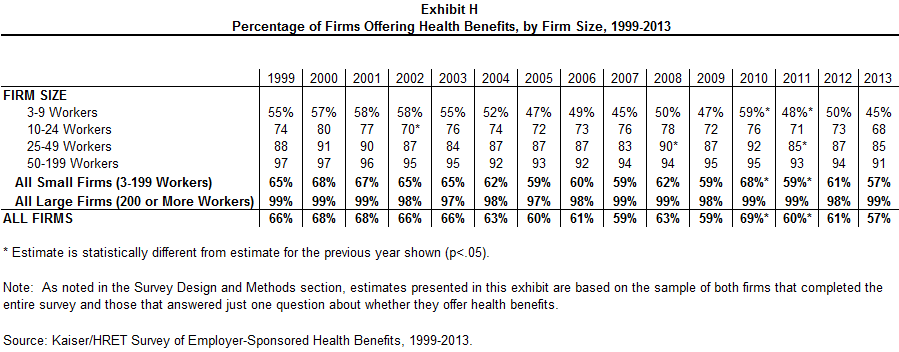

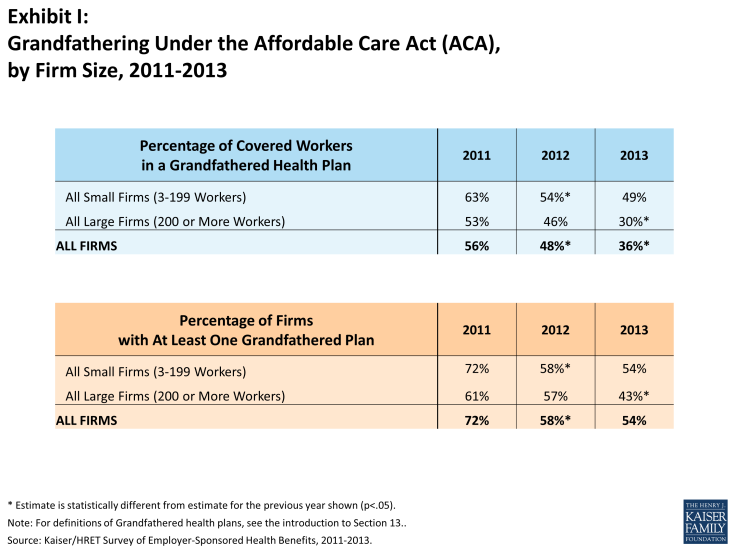

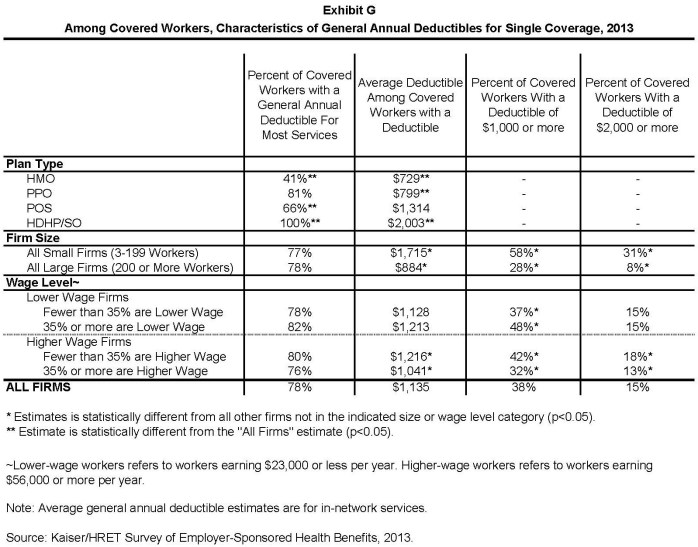

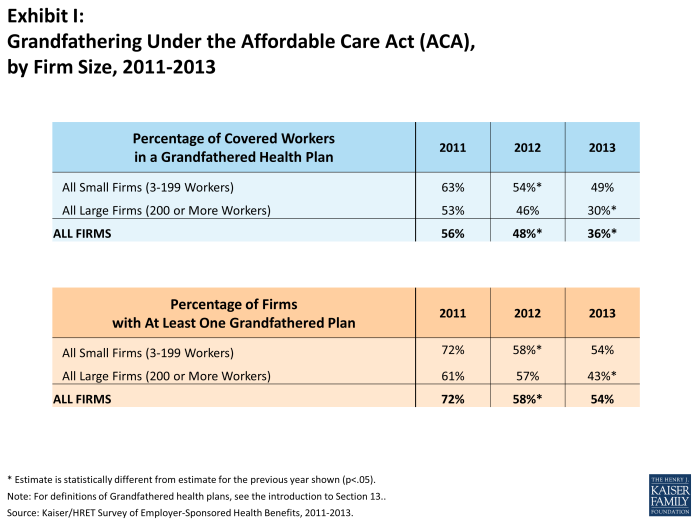

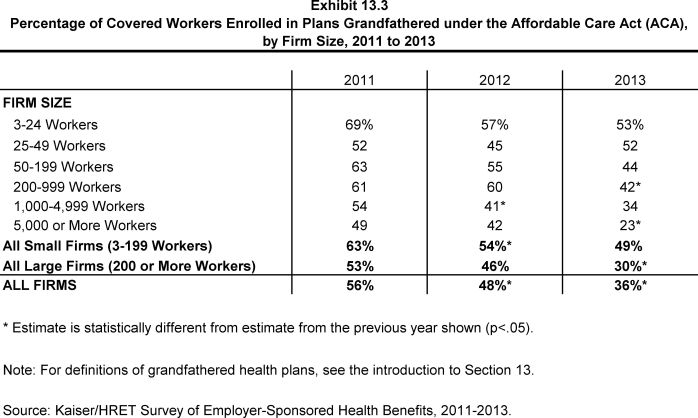

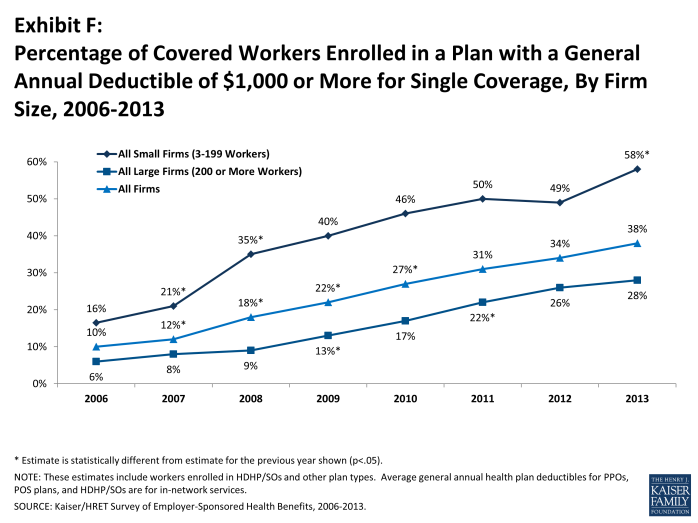

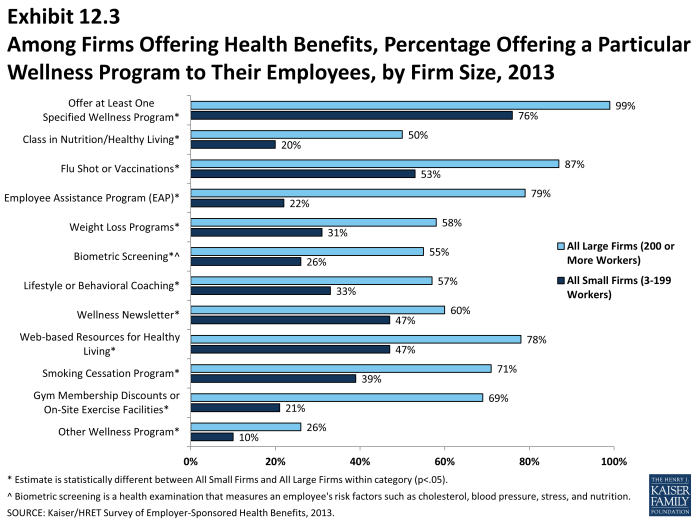

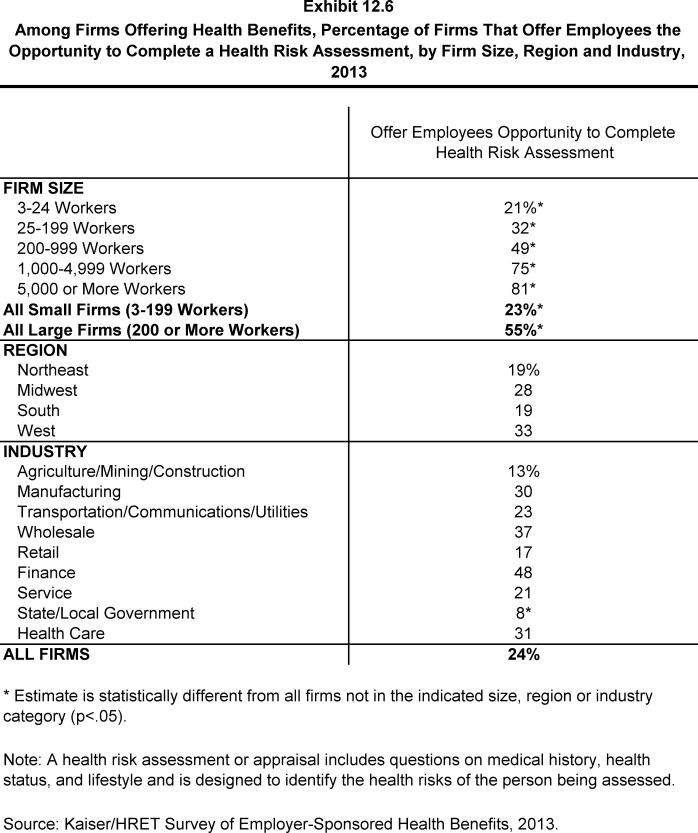

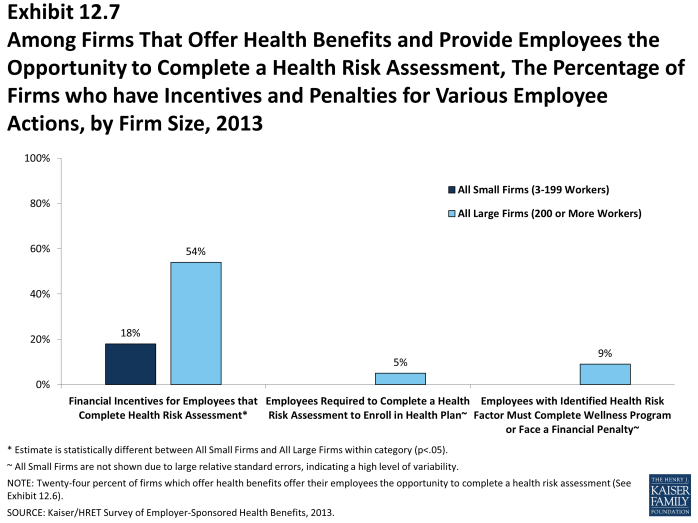

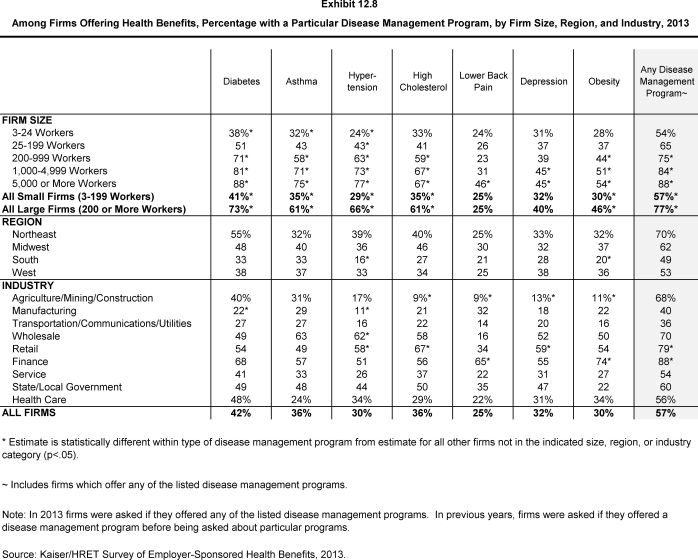

The key findings from the survey, conducted from January through May 2013, include modest increases in premiums for both single coverage (5%) and family coverage (4%). Covered workers generally face similar premium contributions and cost-sharing requirements in 2013 compared to 2012. However, the percentage of covered workers enrolled in plan with a general annual deductible increased in 2013, to over three quarters of covered workers (78%). Additionally, over half (58%) of covered workers at small firms (3-199 workers) now have a deductible of a $1,000 dollars or more. The percentage of firms (57%) which offer health benefits to at least some of their employees and the percentage of workers covered at those firms (62%) are statistically unchanged from 2012. The percentage of covered workers enrolled in grandfathered health plans – those plans exempt from many provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – declined to 36% of covered workers from 48% in 2012 and 56% in 2011. Firms offering health benefits continue to offer wellness and health promotion programs: 77% of firms offer at least one wellness program, 24% offer employees health risk assessments, and 57% offer at least one disease management program. Small percentages of these firms use financial incentives in order to encourage workers to participate or complete these activities.

HEALTH INSURANCE PREMIUMS AND WORKER CONTRIBUTIONS

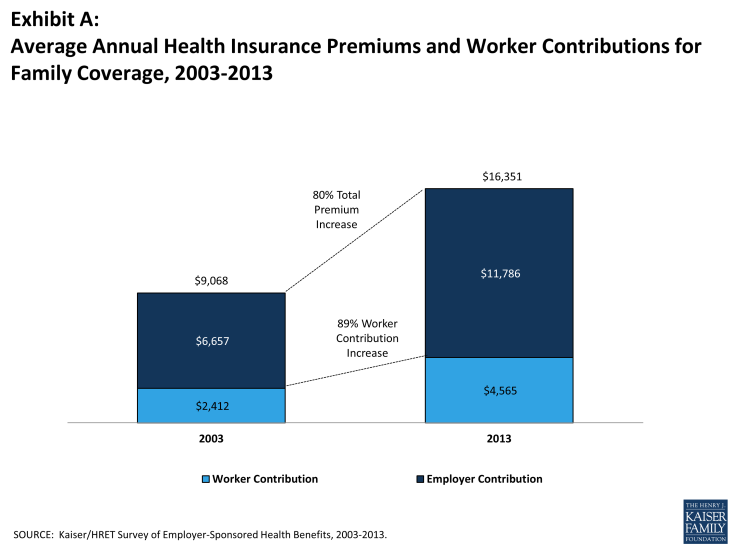

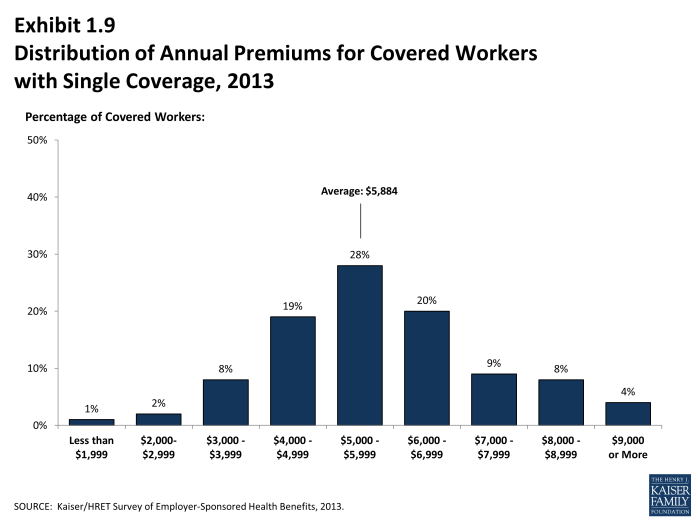

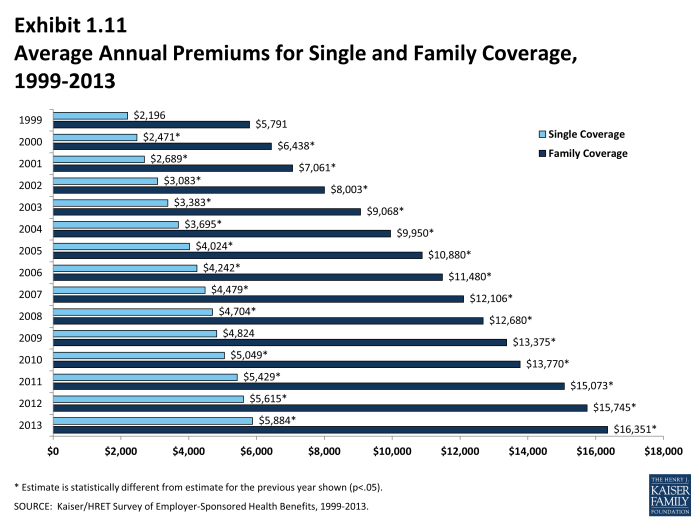

In 2013, the average annual premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance are $5,884 for single coverage and $16,351 for family coverage. The single premium is 5% higher and the family premium is 4% higher than the 2012 average premiums. During the same period workers’ wages increased 1.8% and inflation increased 1.1%.2 Over the last 10 years, the average premium for family coverage has increased 80% (Exhibit A).

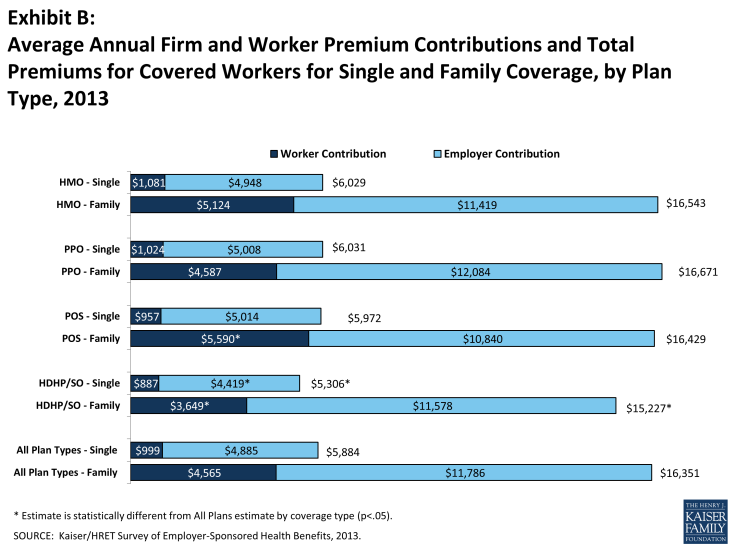

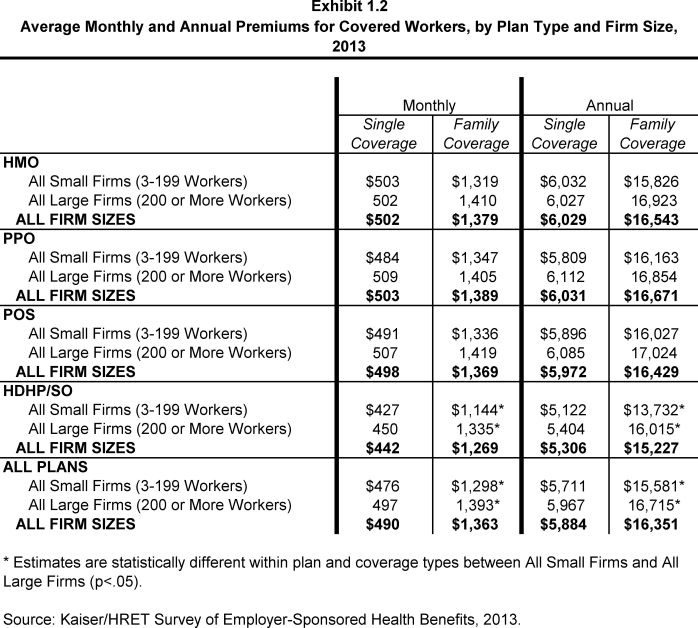

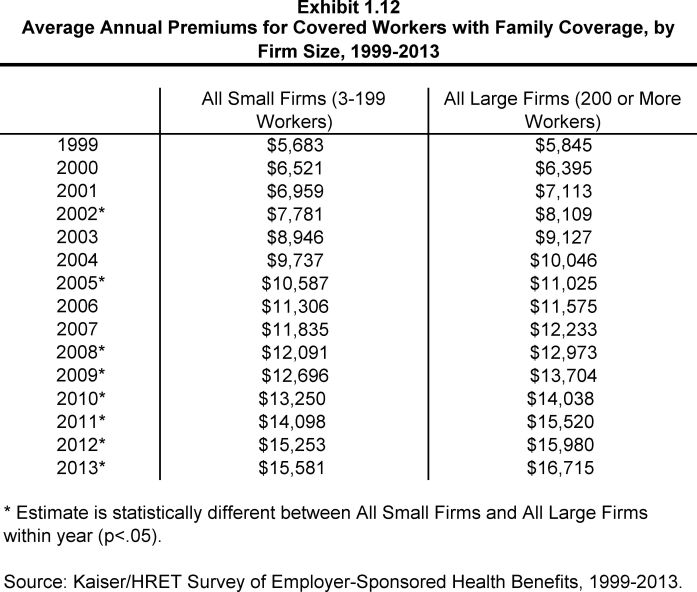

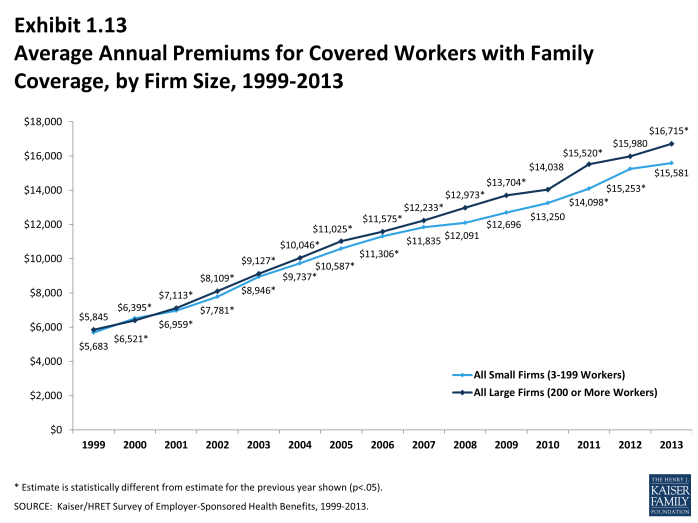

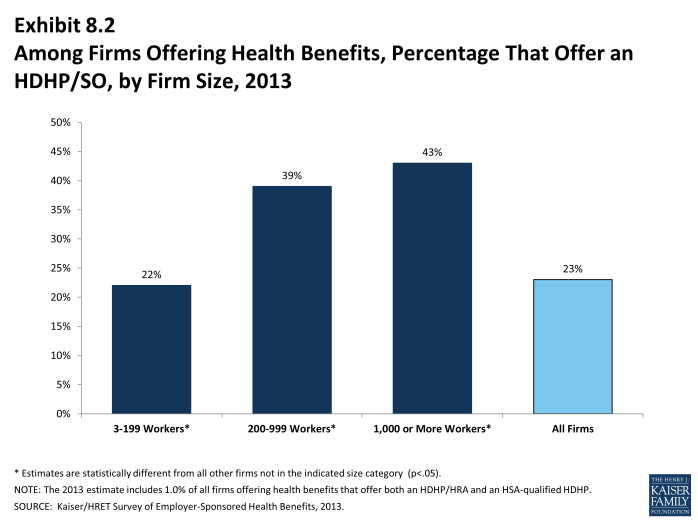

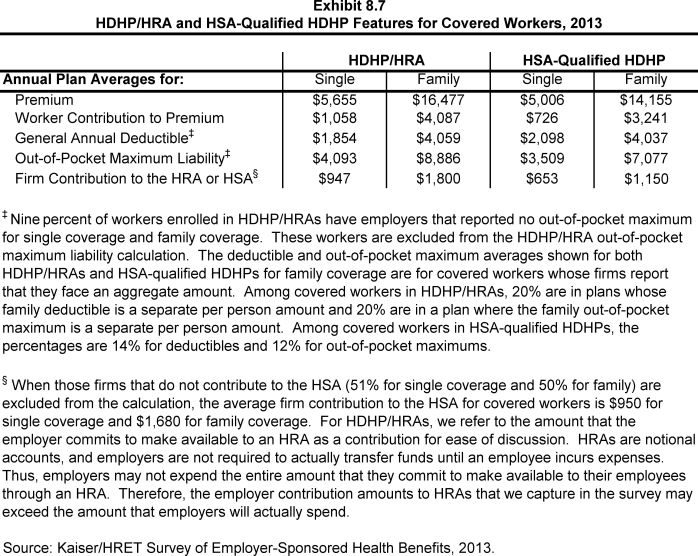

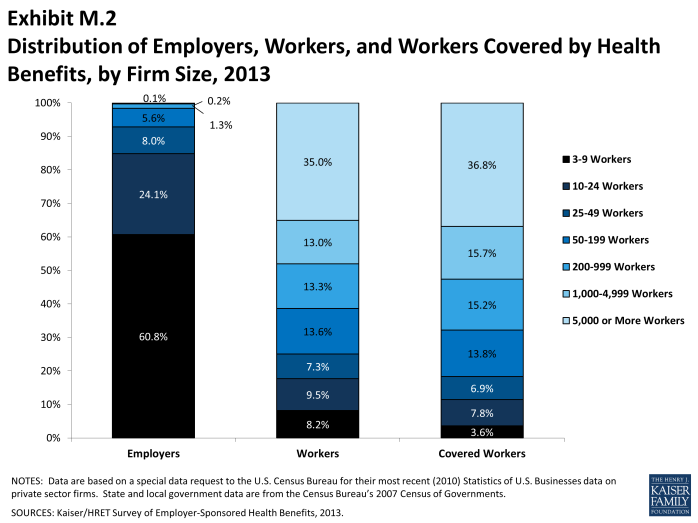

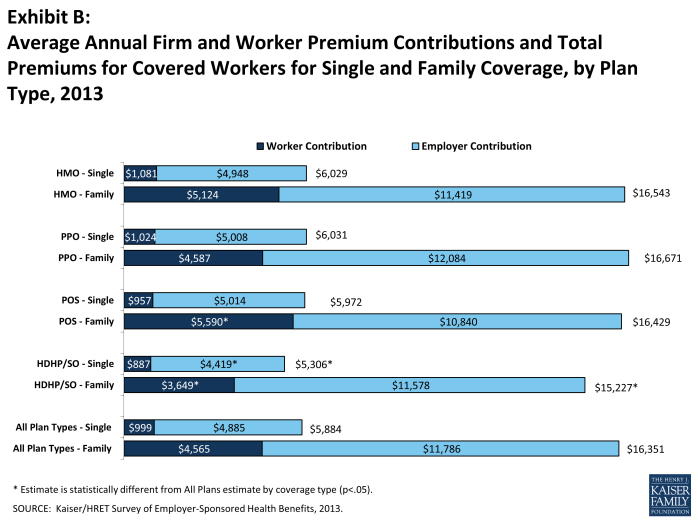

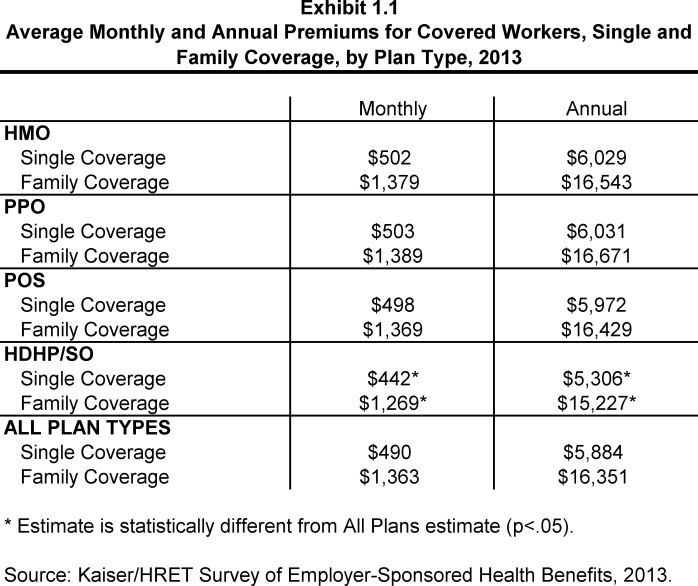

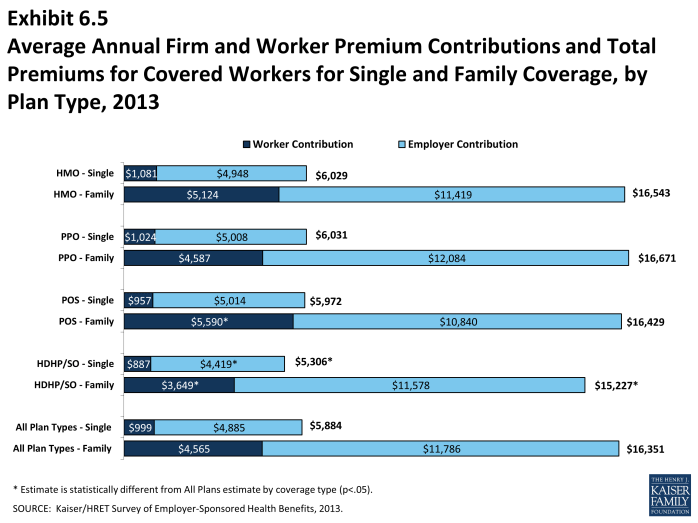

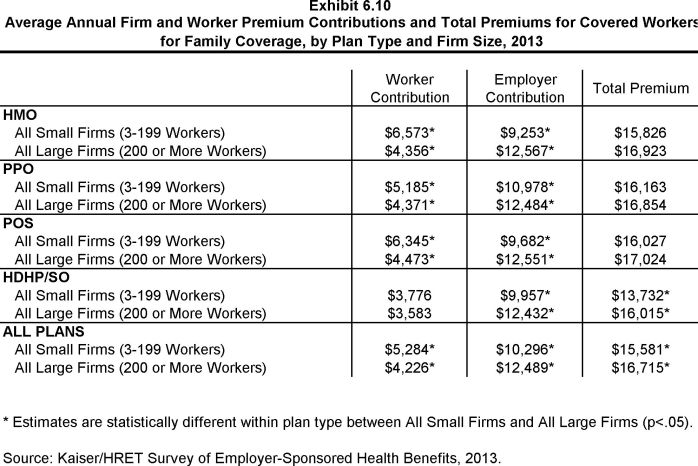

Average premiums for high-deductible health plans with a savings option (HDHP/SOs) are lower than the overall average for all plan types for both single and family coverage (Exhibit B), at $5,306 and $15,227, respectively. Looking at firm size, the average premium for family coverage is lower for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) than for workers in larger firms ($15,581 vs. $16,715).

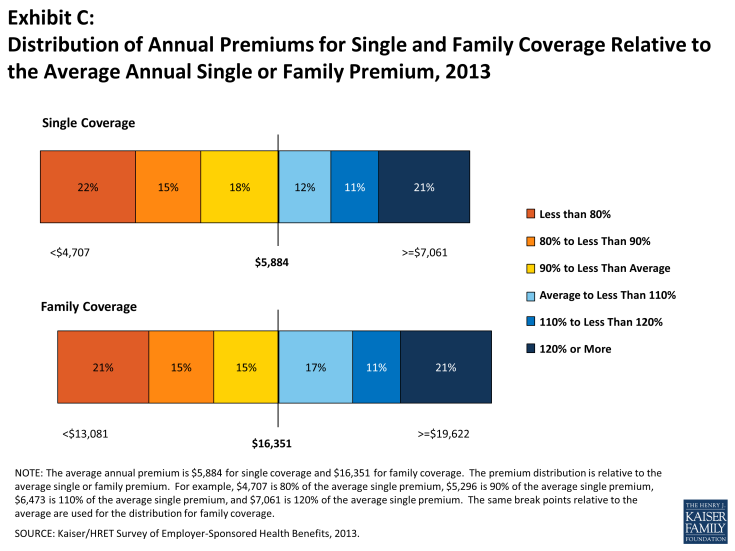

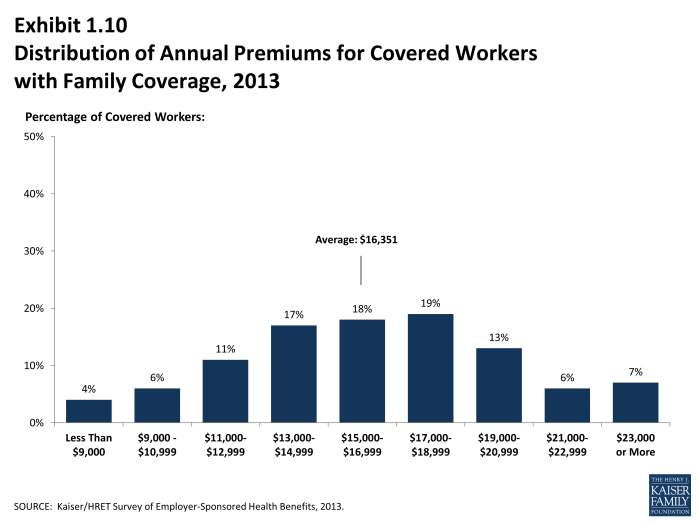

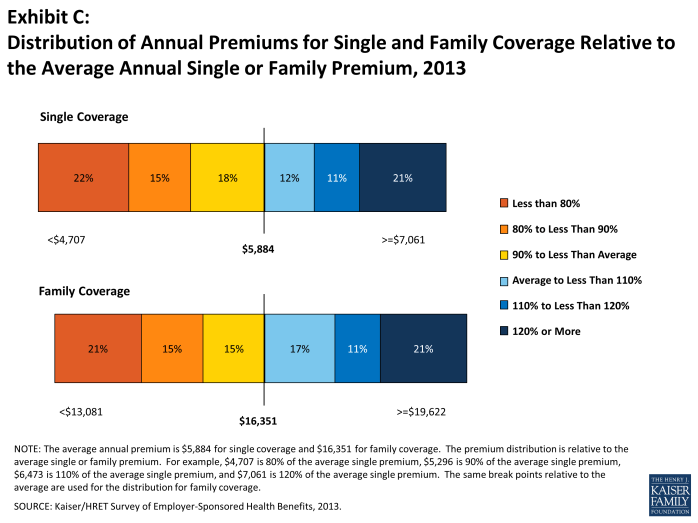

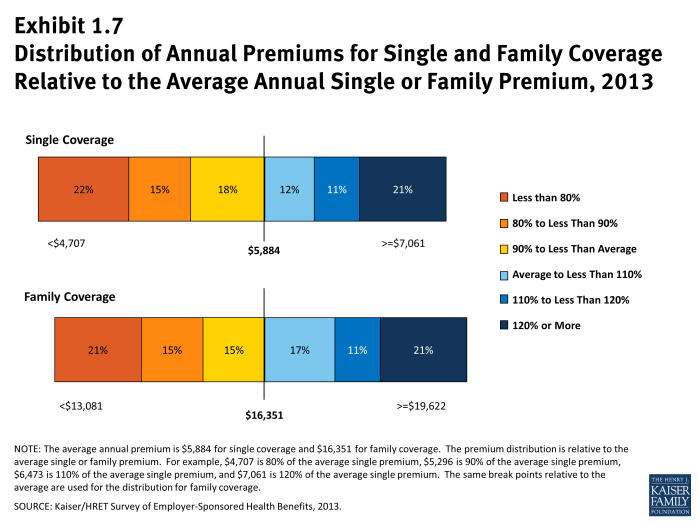

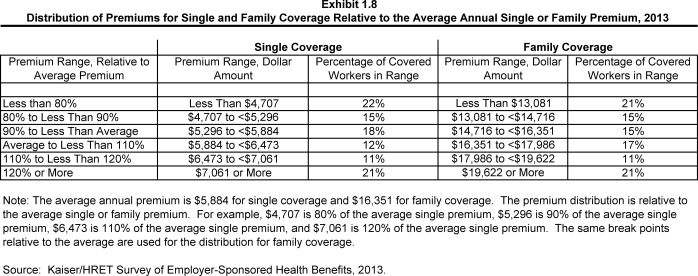

There is significant variation around the average single and family premiums, resulting from differences in benefits, cost sharing, covered populations, and geographical location. Twenty-one percent of covered workers are in plans with an annual total premium for family coverage of at least $19,622 (120% of the average family premium), while 21% of covered workers are in plans where the family premium is less than $13,081 (80% of the average family premium). The distribution is similar around the average single premium (Exhibit C).

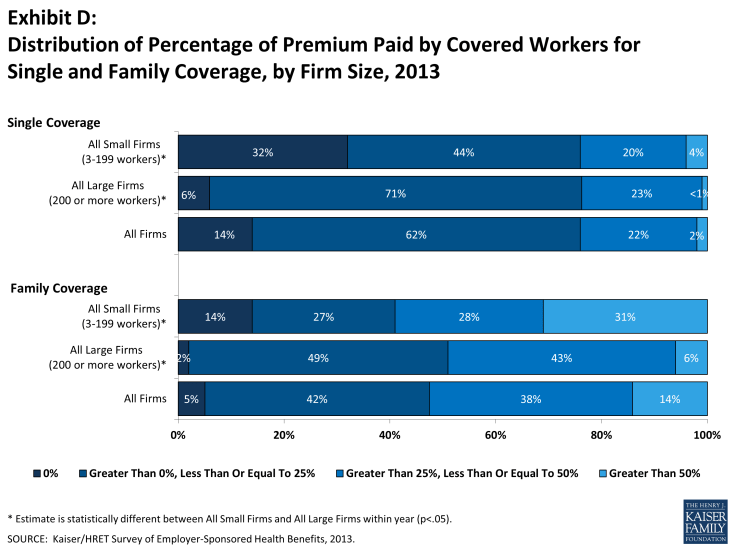

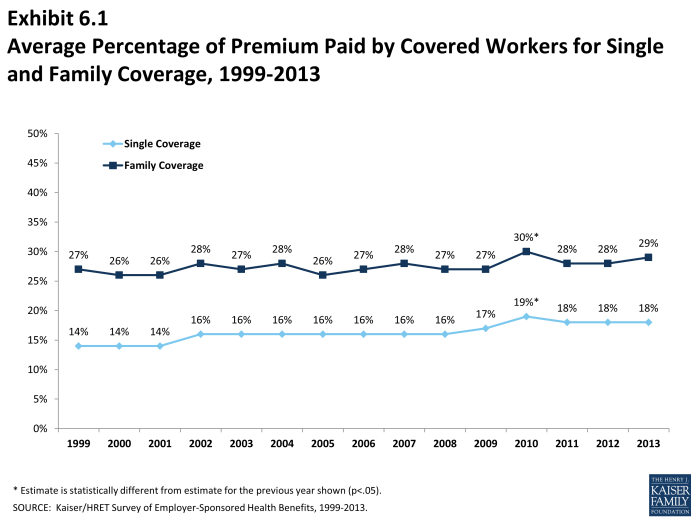

Most often, employers require that workers make a contribution towards the cost of the premium. Covered workers contribute on average 18% of the premium for single coverage and 29% of the premium for family coverage, similar to the percentages contributed in 2012 and relatively unchanged over the past decade. Workers in small firms (3 – 199 workers) contribute a lower average percentage for single coverage compared to workers in larger firms (16% vs. 19%), but they contribute a higher average percentage for family coverage (36% vs. 26%). Workers in firms with a higher percentage of lower-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less) contribute higher percentages of the premium for single coverage (23% vs. 17%) and for family coverage (39% vs. 29%) than workers in firms with a smaller share lower-wage workers.

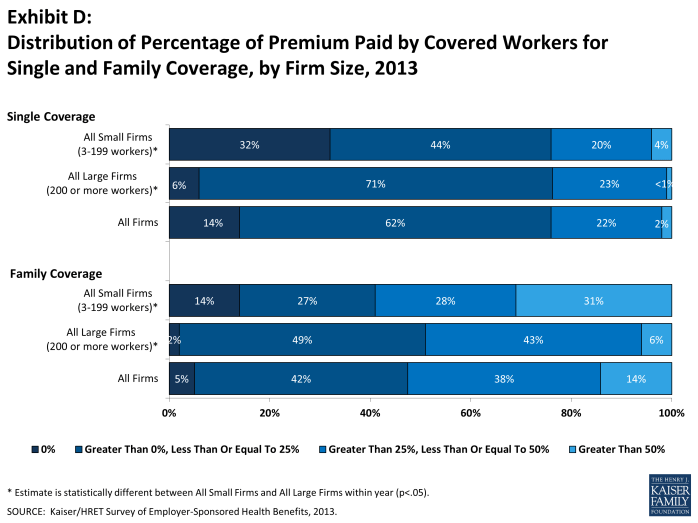

As with total premiums, the share of the premium contributed by workers varies considerably among firms. For single coverage, 62% of covered workers are in plans that require them to make a contribution of less than or equal to a quarter of the total premium, 2% are in plans that require a contribution of more than half of the premium, and 14% are in plans that require no contribution at all. For family coverage, 42% of covered workers are in plans that require them to make a contribution of less than or equal to a quarter of the total premium and 14% are in plans that require more than half of the premium, while only 5% are in plans that require no contribution at all for family coverage (Exhibit D).

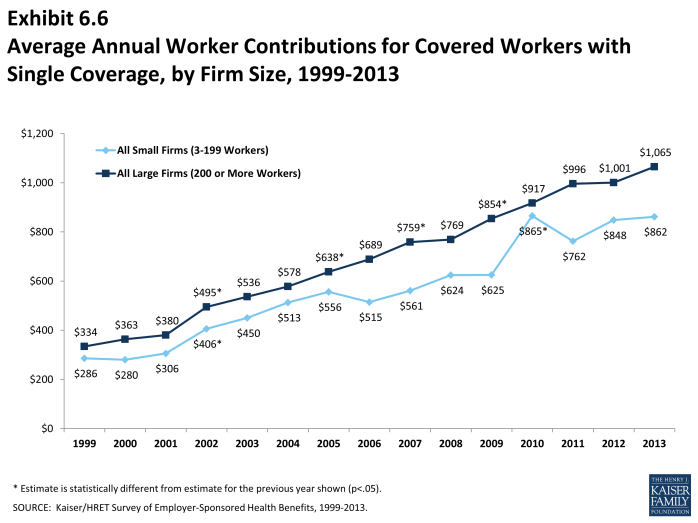

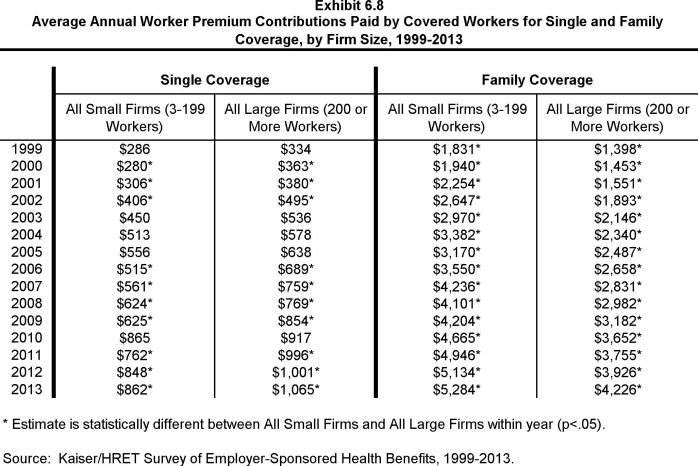

Looking at the dollar amounts that workers contribute, the average annual premium contributions in 2013 are $999 for single coverage and $4,565 for family coverage. Neither amount is a statistically significant increase over the 2012 values ($951 and $4,316, respectively). Covered workers’ average dollar contribution to family coverage has increased 89% since 2003 and 36% since 2008 (Exhibit A). Workers in small firms (3 – 199 workers) have lower average contributions for single coverage than workers in larger firms ($862 vs. $1,065), but higher average contributions for family coverage ($5,284 vs. $4,226). Workers in firms with a higher percentage of lower-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less) have higher average contributions for single coverage ($1,234 vs. $979) and for family coverage ($5,818 vs. $4,455) than workers in firms with lower percentages of lower-wage workers.

PLAN ENROLLMENT

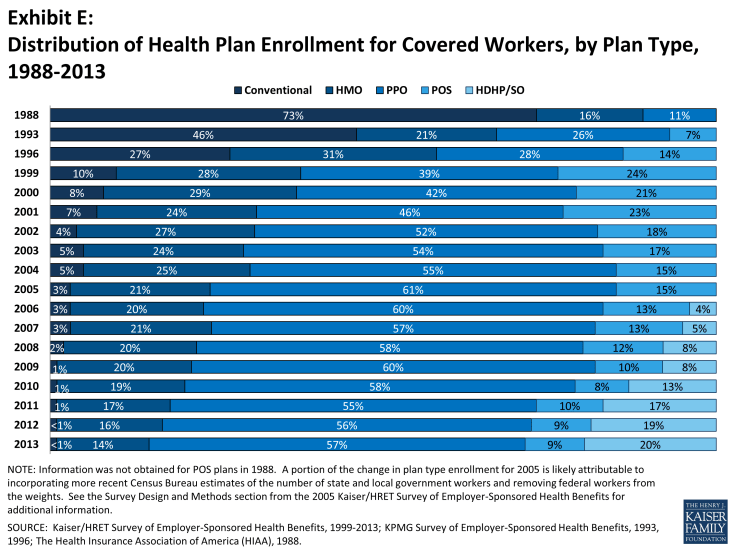

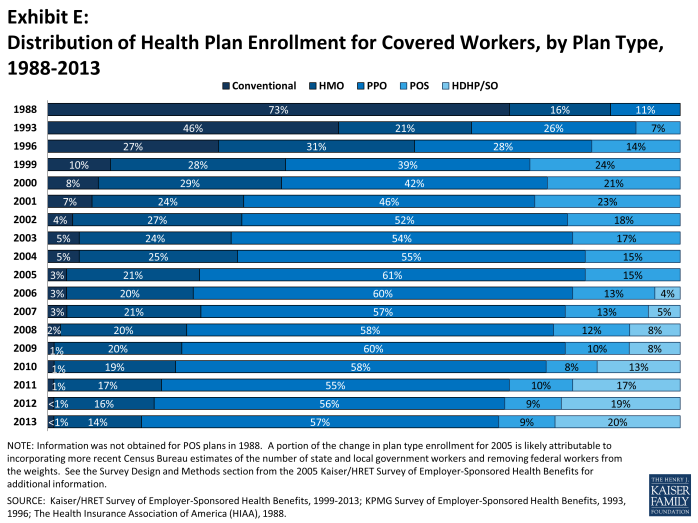

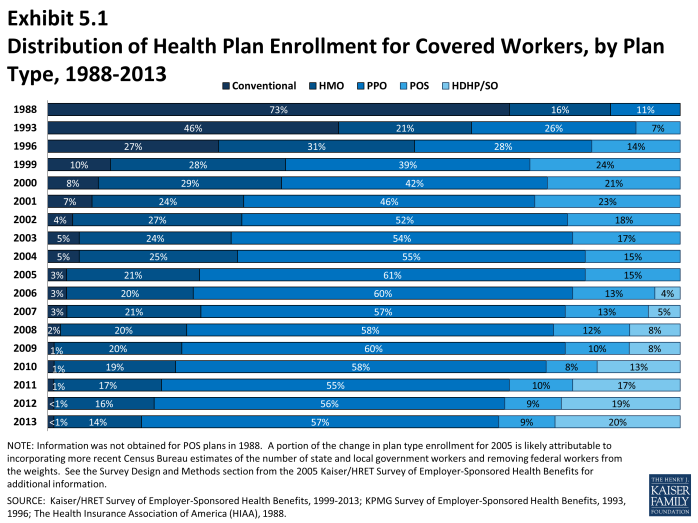

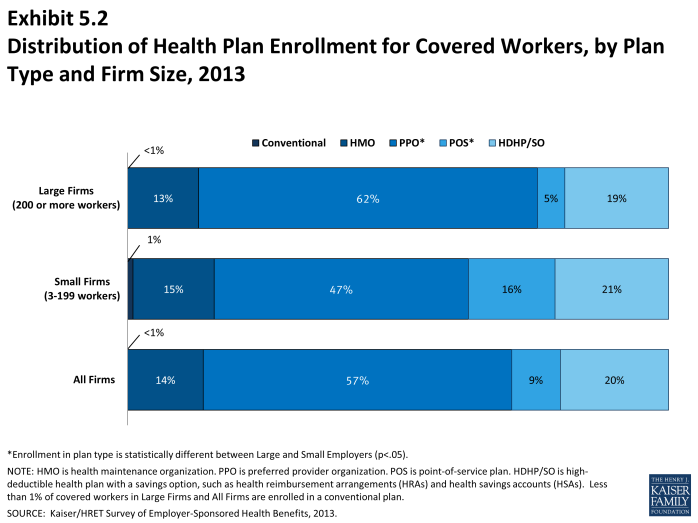

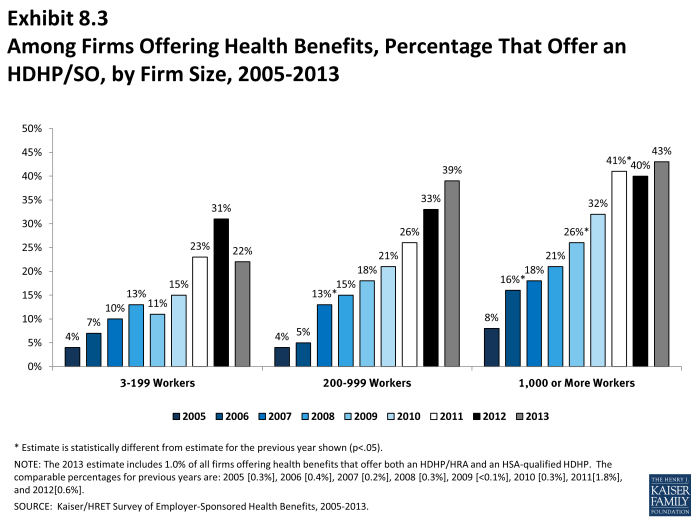

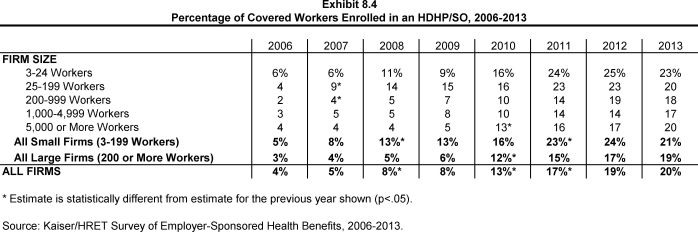

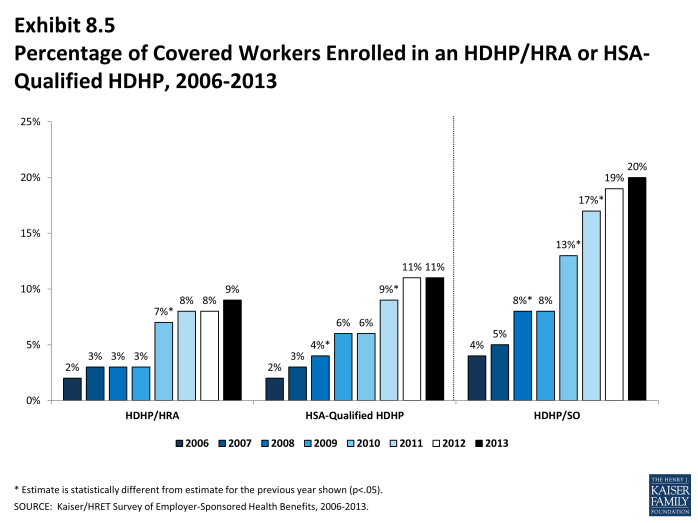

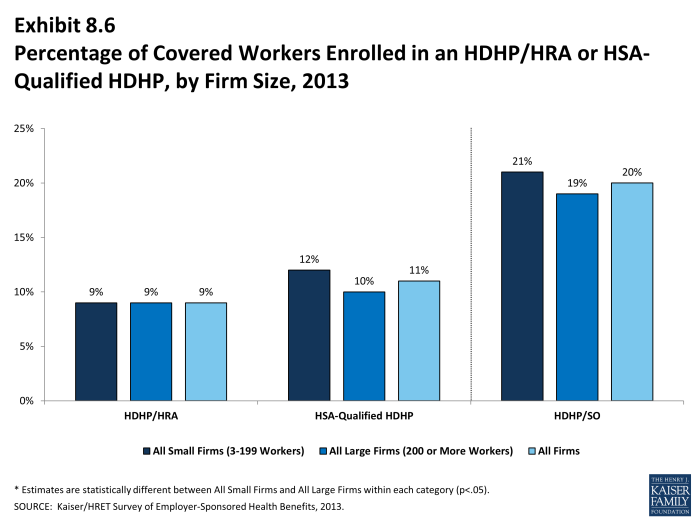

PPO plans remain the most common plan type, enrolling 57% of covered workers in 2013. Twenty percent of covered workers are enrolled in an HDHP/SO, 14% in an HMO, 9% in a POS plan, and less than 1% in a conventional plan (Exhibit E). Enrollment in HDHP/SOs increased significantly between 2009 and 2011, from 8% to 17% of covered workers, but has plateaued since then (Exhibit E). Enrollment distribution varies by firm size, for example, PPOs are relatively more popular for covered workers at large firms (200 or more workers) than smaller firms (62% vs. 47%) and POS plans are relatively more popular among smaller firms than large firms (16% vs. 5%).

EMPLOYEE COST SHARING

Most covered workers face additional plan costs when they use health care services. Seventy-eight percent of covered workers have a general annual deductible for single coverage that must be met before most services are reimbursed by the plan. Even workers without a general annual deductible often face other types of cost sharing when they use services, such as copayments or coinsurance for office visits and hospitalizations.

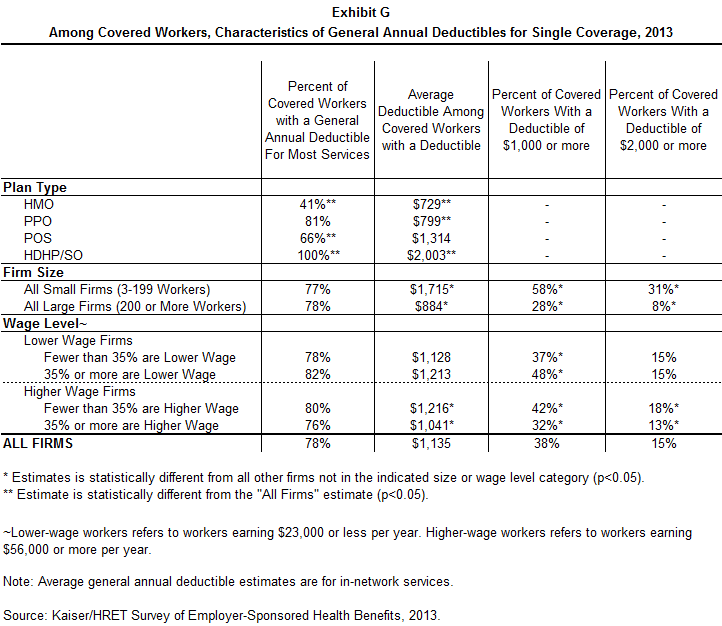

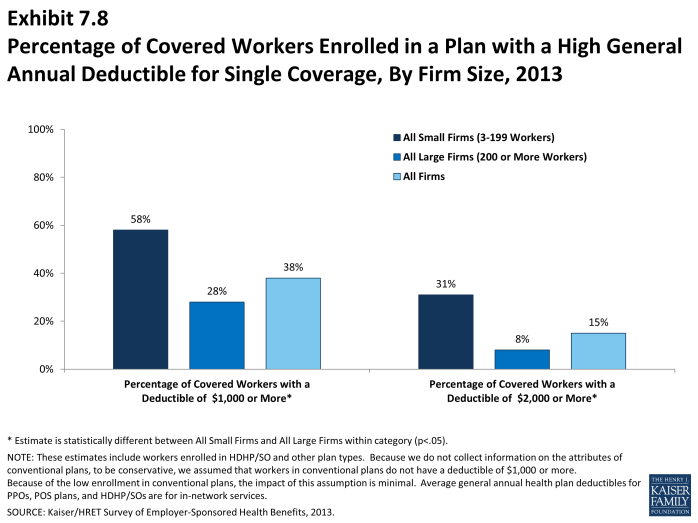

Among covered workers with a general annual deductible, the average deductible amount for single coverage is $1,135. The average annual deductible is unchanged from 2012 ($1,097), but has increased from $735 dollars in 2008. Deductibles differ by firm size: for workers in plans with a deductible, the average deductible for single coverage is $1,715 in small firms (3-199 workers), compared to $884 for workers in larger firms (Exhibit G). Among all covered workers, 58% in small firms (3-199 workers) and 28% in larger firms are in a plan with a deductible of at least $1,000 for single coverage (Exhibit F). The percentage of covered workers at small firms (3-199 workers) with a deductible of a $1,000 or more increased significantly in 2013 from 49% in 2012.

The large majority of workers also have to pay a portion of the cost of physician office visits. Almost three-in-four covered workers pay a copayment (a fixed dollar amount) for office visits with a primary care physician (74%) or a specialist physician (72%), in addition to any general annual deductible their plan may have. Smaller shares of workers pay coinsurance (a percentage of the covered amount) for primary care office visits (20%) or specialty care visits (20%). For in-network office visits, covered workers with a copayment pay an average of $23 for primary care and $35 for specialty care. For covered workers with coinsurance, the average coinsurance for office visits is 18% for primary and for specialty care. While the survey collects information only on in-network cost sharing, it is generally understood that out-of-network cost sharing is higher.

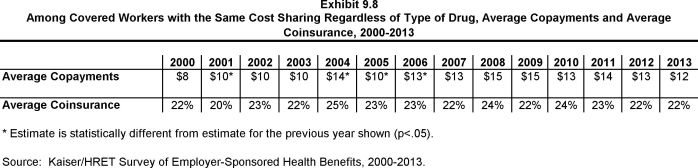

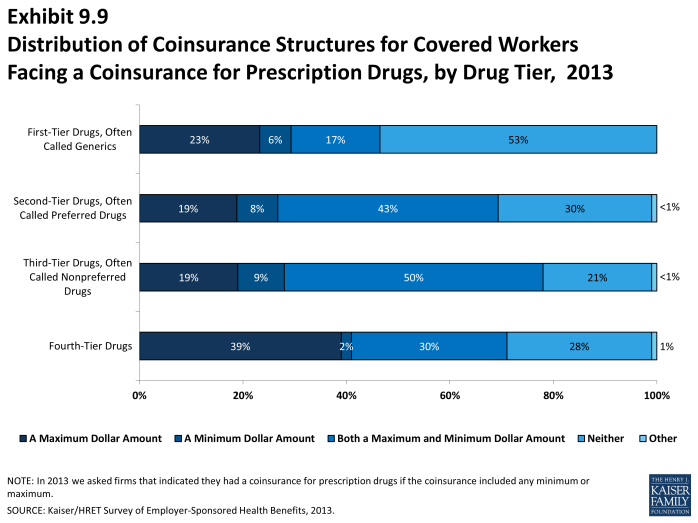

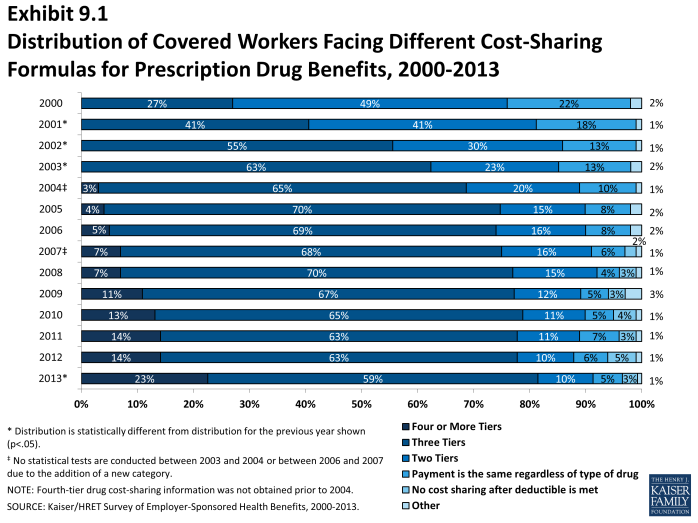

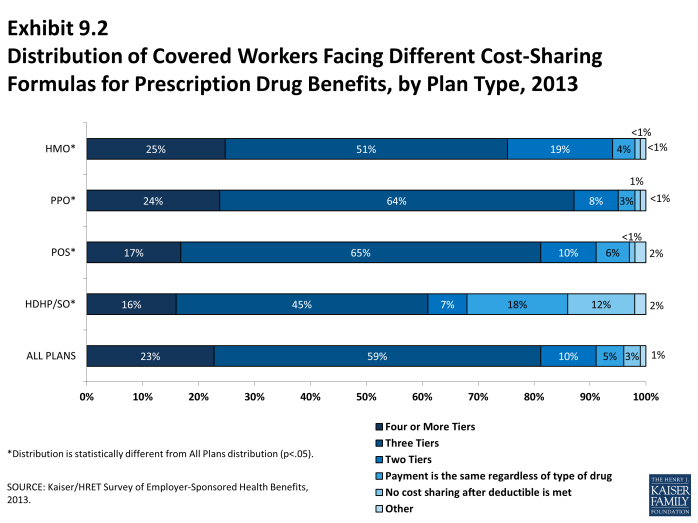

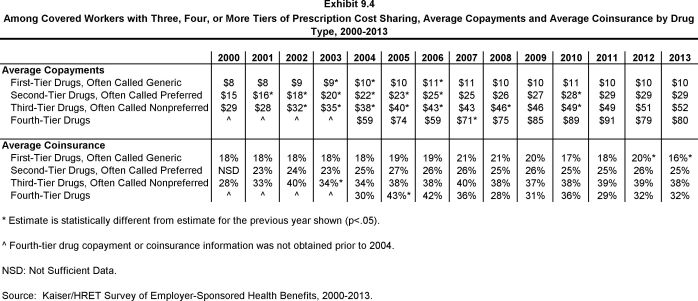

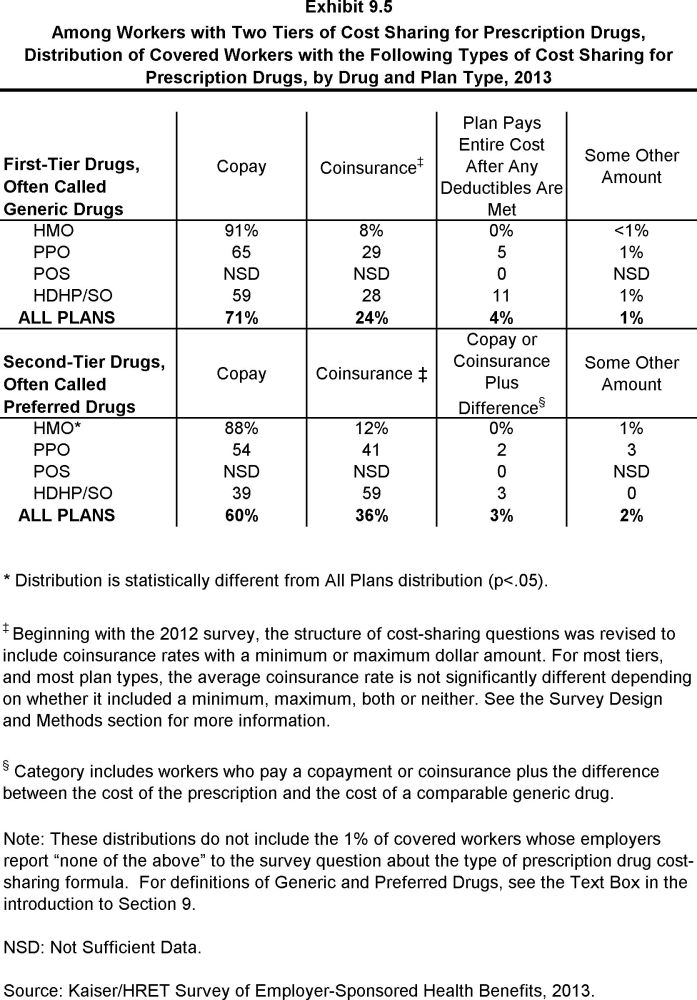

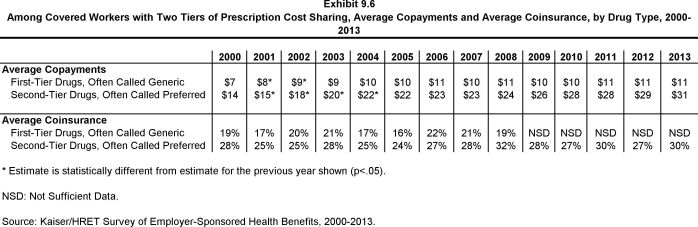

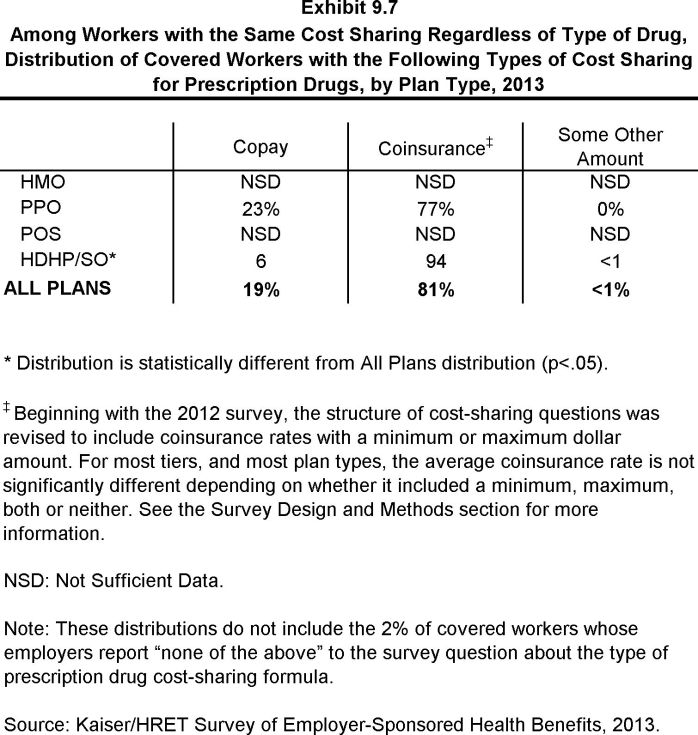

The cost sharing that a person pays when they fill a prescription usually varies with the type of drug – for example whether it is a generic, brand-name or specialty drug – and whether the drug is considered preferred or not on the plan’s formulary. These factors result in each drug being assigned to a tier that represents a different level, or type, of cost sharing. Eighty-one percent of covered workers are in plans with three-or-more tiers of cost sharing. Copayments are the most common form of cost sharing for tiers one through three and coinsurance is the most common form of cost sharing for drugs on the fourth or higher tier of formularies. Among workers with three-or-more tier plans, the average copayments in these plans are $10 for first-tier drugs, $29 for second-tier drugs, $52 for third-tier drugs, and $80 for fourth-tier drugs – similar to the amounts reported last year. HDHP/SOs have a somewhat different cost-sharing pattern for prescription drugs than other plan types: just 61% of covered workers are enrolled in a plan with three-or-more tiers of cost sharing, while 12% are in plans that pay the full cost of prescriptions once the plan deductible is met, and 18% are in a plan with the same cost sharing for all prescription drugs.

Most workers also face additional cost sharing for a hospital admission or an outpatient surgery episode. After any general annual deductible is met, 61% of covered workers have a coinsurance and 16% have a copayment for hospital admissions. Lower percentages have per day (per diem) payments (7%), a separate hospital deductible (3%), or both copayments and coinsurance (8%). The average coinsurance rate for hospital admissions is 18%, the average copayment is $278 per hospital admission, the average per diem charge is $264, and the average separate annual hospital deductible is $436. The cost-sharing provisions for outpatient surgery are similar to those for hospital admissions, as most covered workers have either coinsurance (62%) or copayments (18%). For covered workers with cost sharing for each outpatient surgery episode, the average coinsurance is 18% and the average copayment is $140.

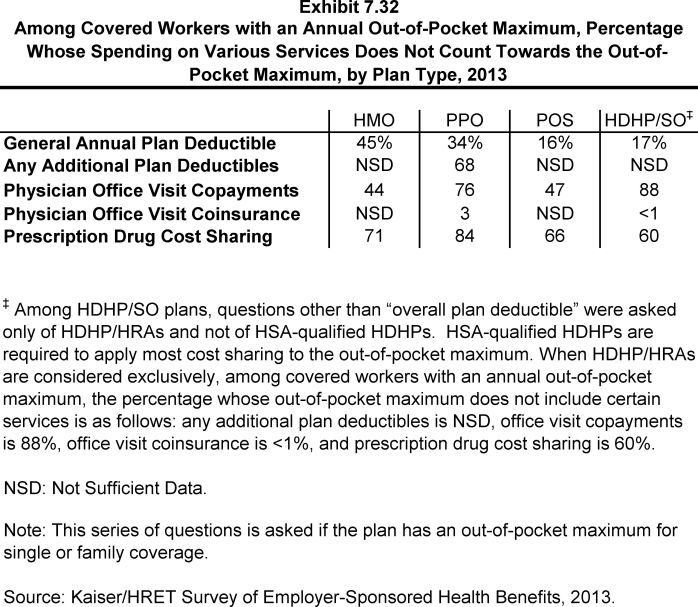

Most plans limit the amount of cost sharing workers must pay each year, generally referred to as an out-of-pocket maximum. Eighty-eight percent of covered workers have an out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage, but the actual dollar limits differ considerably. For example, among covered workers in plans that have an out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage, 43% are in plans with an annual out-of-pocket maximum of $3,000 or more, and 15% are in plans with an out-of-pocket maximum of less than $1,500. Even in plans with a specified out-of-pocket limit, not all spending is counted towards meeting the limit. For example, among workers in PPOs with an out-of-pocket maximum, 76% are in plans that do not count towards physician office visit copayments, 34% are in plans that do not count towards spending on the general annual deductible, and 84% are in plans that do not count towards prescription drug spending when determining if an enrollee has reached the out-of-pocket limit. The ACA will require that all non-grandfathered plans have an out-of-pocket maximum that counts all cost sharing towards the limit.

AVAILABILITY OF EMPLOYER-SPONSORED COVERAGE

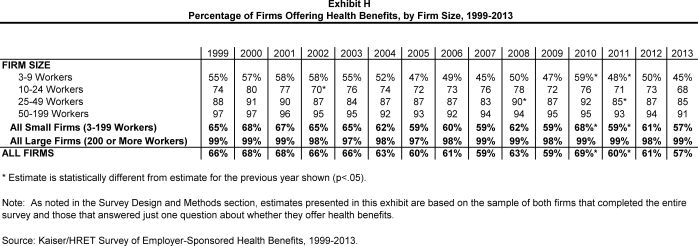

Fifty-seven percent of firms offer health benefits to their workers, statistically unchanged from the percentage that offered last year (61%) (Exhibit H). The offer rate is similar between 2012 and 2013 for both small firms (3 – 199 workers) and larger firms. The likelihood of offering health benefits differs significantly by size of firm, with only 45% of employers with 3 to 9 workers offering coverage, but virtually all employers with 1,000 or more workers offering coverage to at least some of their employees. Ninety percent of workers are in a firm that offers health benefits to at least some of its employees, similar to 2012 (92%). Offer rates also differ by other firm characteristics; 59% of firms with fewer younger workers (less than 35% of the workers are age 26 or younger) offer health benefits compared to 23% of firms with more younger workers.

Even in firms that offer health benefits, not all workers are covered. Some workers are not eligible to enroll as a result of waiting periods or minimum work-hour rules. Other workers do not enroll in coverage offered to them because of the cost of coverage or because they are covered through a spouse. Among firms that offer coverage, an average of 77% of workers are eligible for the health benefits offered by their employer. Of those eligible, 80% take up their employer’s coverage, resulting in 62% of workers in offering firms having coverage through their employer. Among both firms that offer and do not offer health benefits, 56% of workers are covered by health plans offered by their employer, the same percentage as 2012.

RETIREE COVERAGE

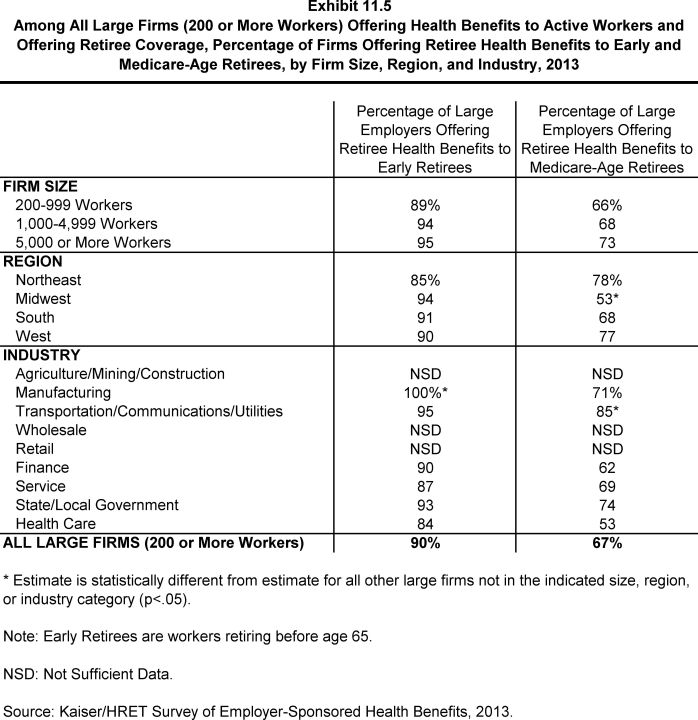

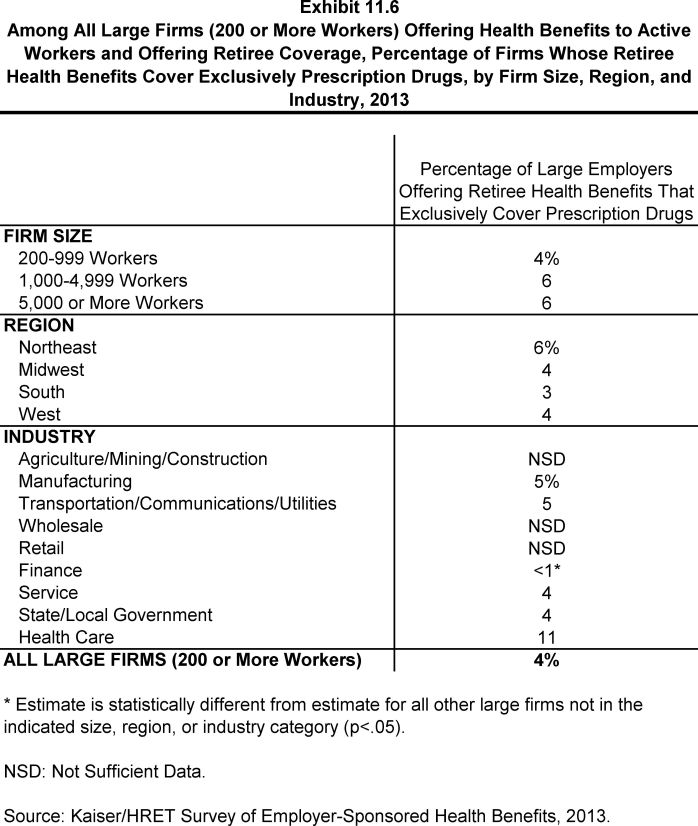

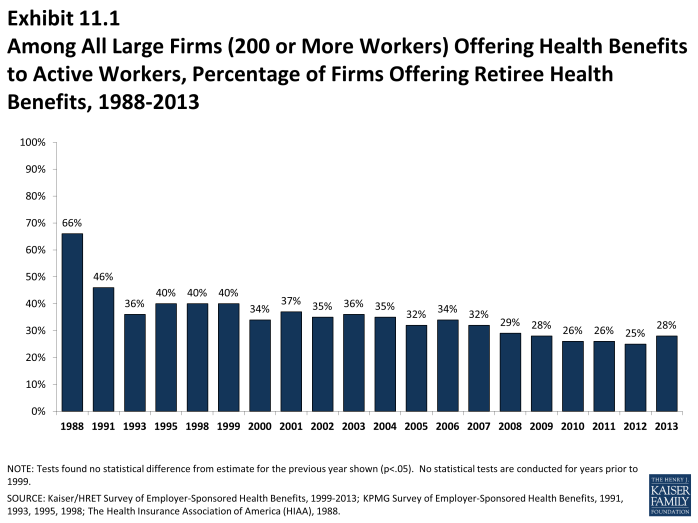

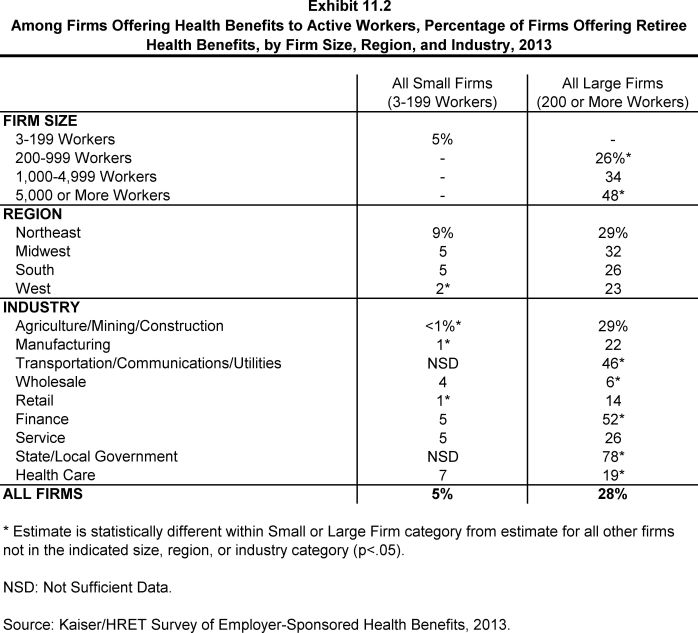

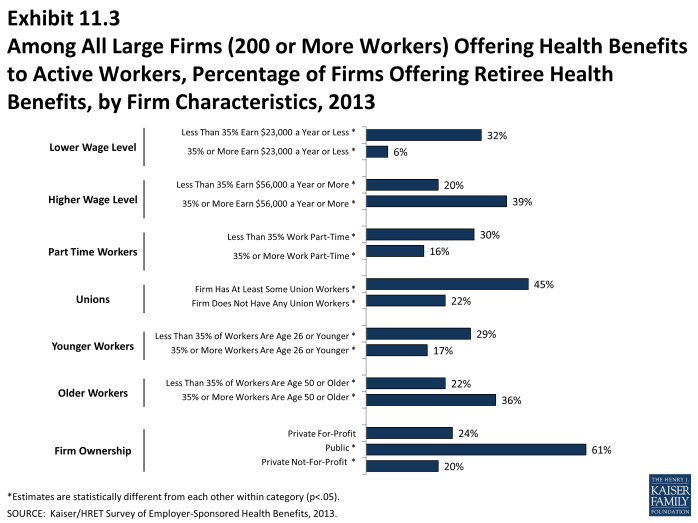

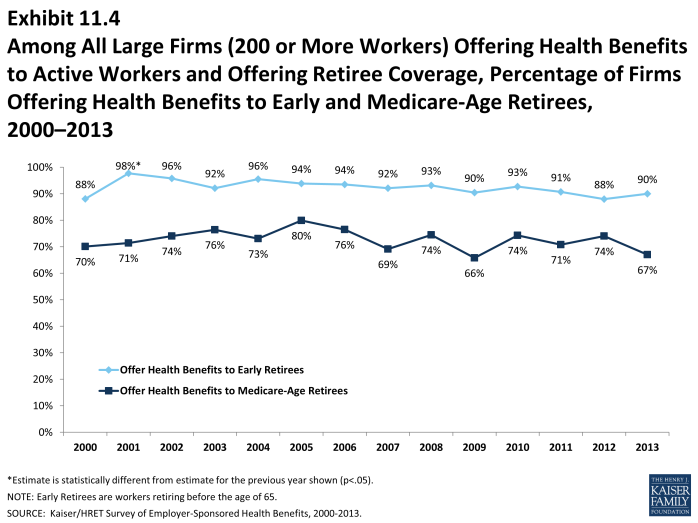

Twenty-eight percent of large firms (200 or more workers) that offer health benefits in 2013 also offer retiree health benefits, similar to the percentage (25%) in 2012. Among large firms (200 or more workers) that offer retiree health benefits, 90% offer health benefits to early retirees (workers retiring before age 65), 67% offer health benefits to Medicare-age retirees, and 4% offer a plan that covers exclusively prescription drugs.

WELLNESS

Employers continue to offer programs in large numbers that help employees identify issues with their health and engage in healthier behavior. These include offering their employees the opportunity to complete a health risk assessment, and offering a variety of wellness programs that promote healthier lifestyles, including better diet and more exercise. Some employers have begun to collect biometric information from employees (e.g., cholesterol levels and body mass index) and are using it as part of their wellness and health promotion programs.

Almost one-in-four employers (24%) offering health benefits provide employees with an opportunity to complete a health risk assessment. A health risk assessment includes questions about medical history, health status, and lifestyle, and is designed to identify the health risks of the person being assessed. Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely than smaller firms to ask employees to complete a health risk assessment (55% vs. 23%). Among these firms, 54% of large firms (200 or more workers) report that they provide a financial incentive to employees that complete the assessment.

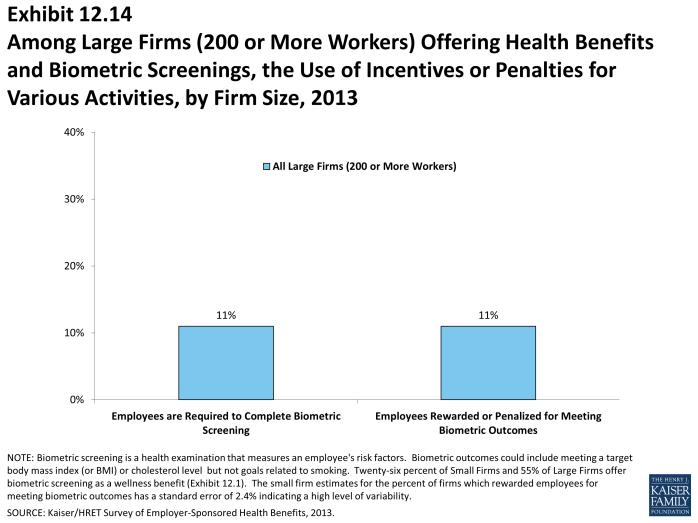

Fifty-five percent of large firms (200 or more workers) and 26% of smaller firms offering health benefits report offering biometric screening to employees. A biometric screening is a health examination that measures an employee’s risk factors, such as body weight, cholesterol, blood pressure, stress, and nutrition. Of these firms, 11% percent of large firms require employees to complete a biometric screening to enroll in the health plan; and 11% of large firms report that employees may be financially rewarded or penalized based in meeting biometric outcomes.

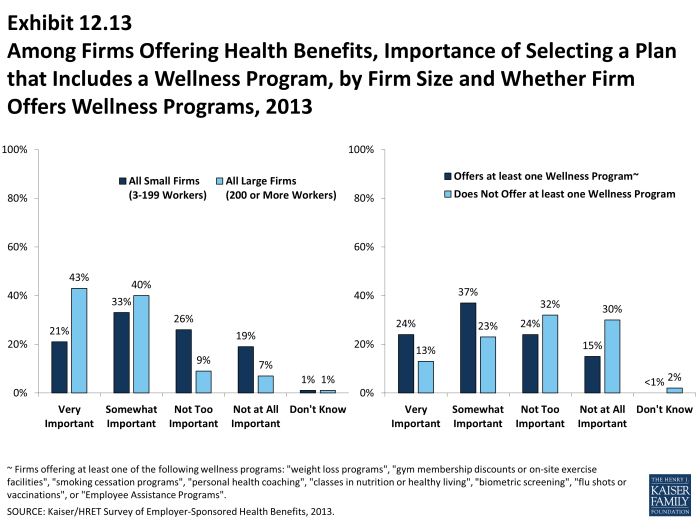

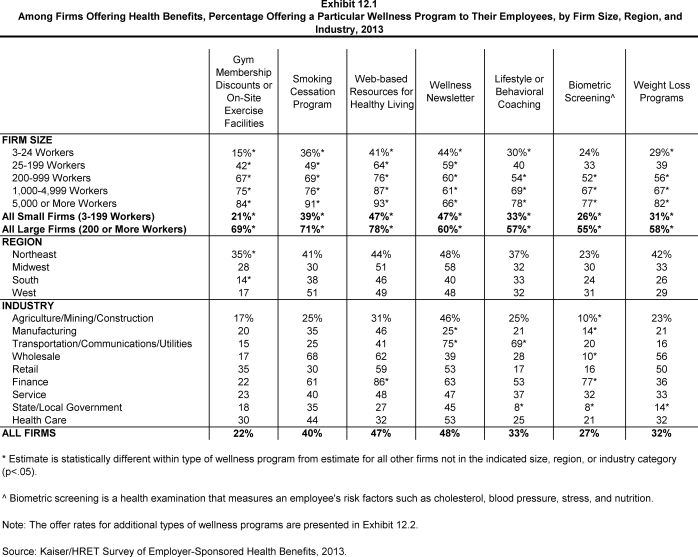

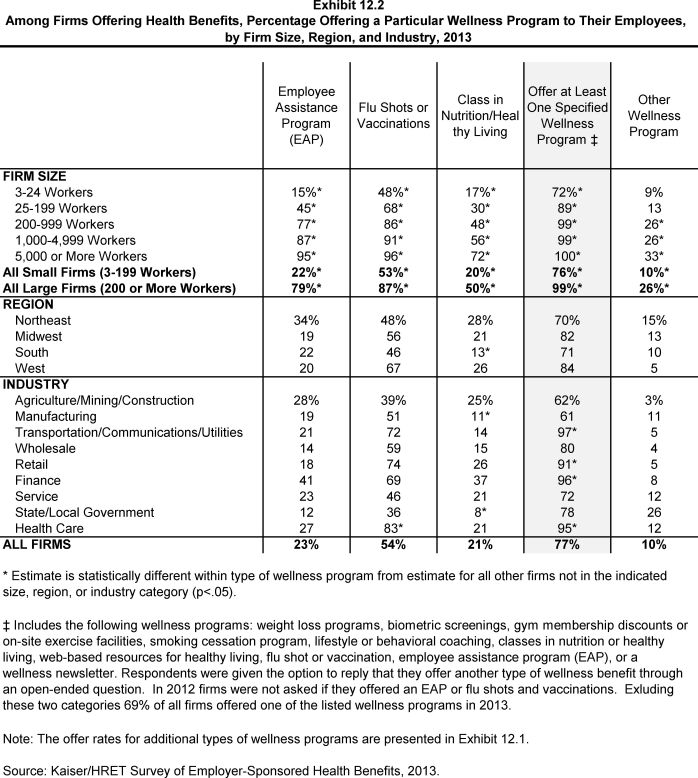

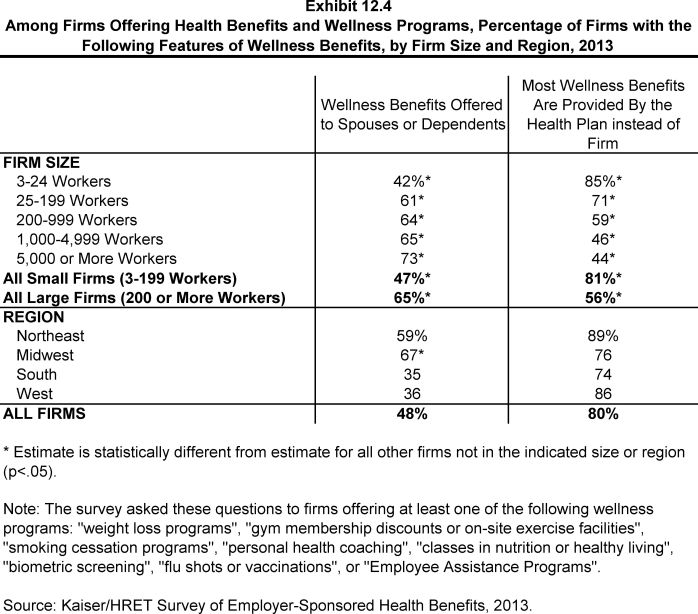

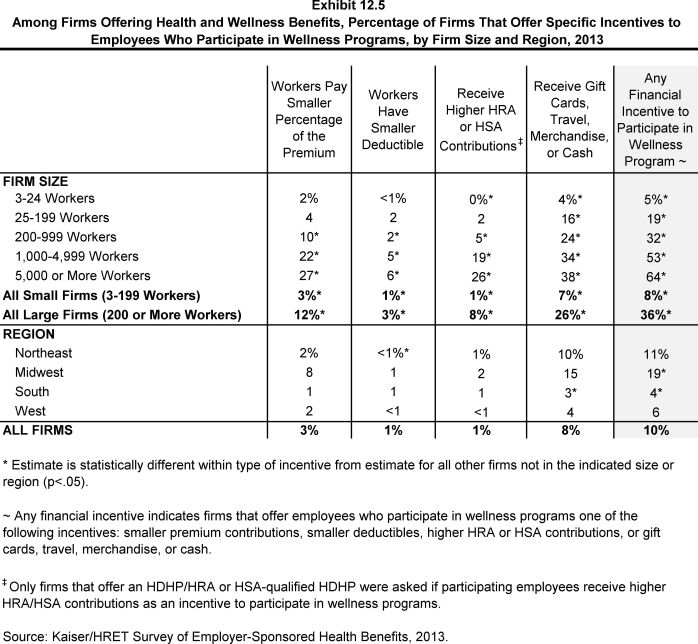

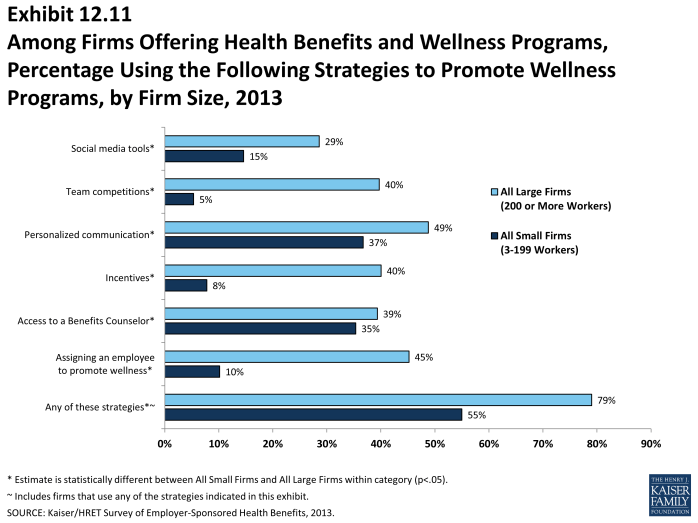

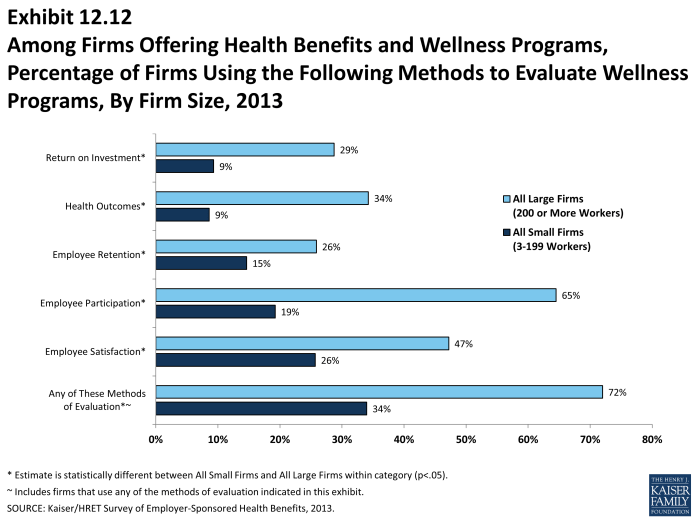

Virtually all large employers (200 or more workers) and most smaller employers offer at least one wellness program. Seventy-seven percent of employers offering health benefits offer at least one of the following wellness programs in 2013: weight loss programs, gym membership discounts or on-site exercise facilities, biometric screening, smoking cessation programs, personal health coaching, classes in nutrition or healthy living, web-based resources for healthy living, flu shots or vaccinations, Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), or a wellness newsletter. Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to offer one of these programs than smaller firms (99% vs. 76%). Of firms offering health benefits and a wellness program, 36% of large firms (200 or more workers) and 8% of smaller firms offer employees a financial incentive to participate in a wellness program, such as smaller premium contributions, smaller deductibles, higher HSA/HRA contributions or gift cards, travel, merchandise or cash.

OTHER EMPLOYER PROGRAMS

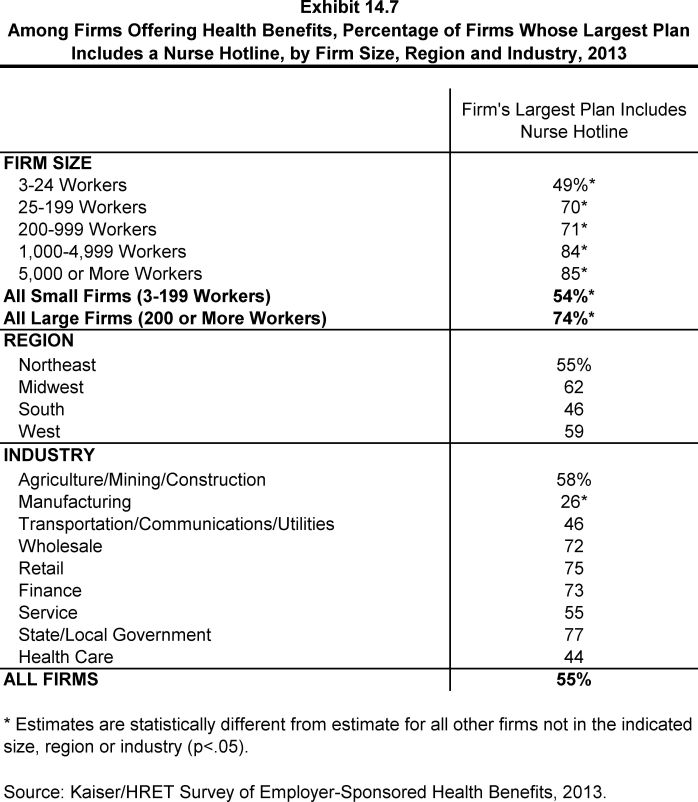

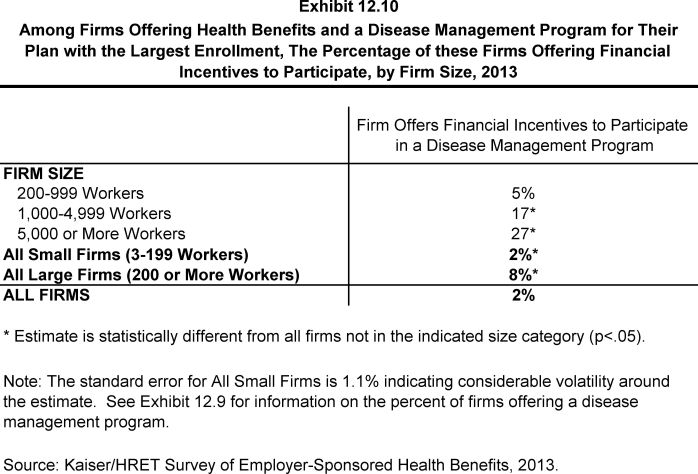

Disease Management Programs. Most employers offer at least one disease management program as part of their largest health plan. Disease management programs identify people with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, depression and hypertension, and offer treatment options to manage or improve the identified condition. Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to have a disease management program as part of their largest health plan than small firms (77% vs. 57%). Only 8% of large firms (200 or more workers) whose largest plan includes a disease management program, have a financial incentive to encourage employees to participate.

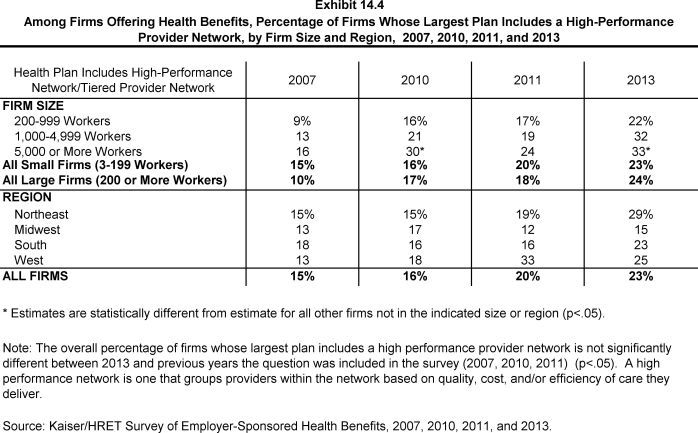

High Performance or Tiered Networks. Almost a quarter (23%) of employers offering health benefits have high performance or tiered networks in their largest health plan. These programs identify providers that are more efficient or have higher quality care, and may provide financial or other incentives for enrollees to use the selected providers.

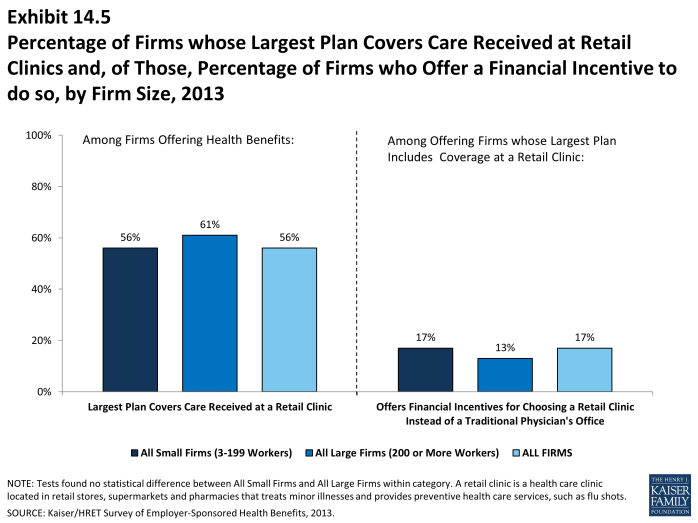

Retail Health Clinics. Fifty-six percent of employers offering health benefits cover services provided by retail health clinics. These may be health clinics located in grocery stores or pharmacies to treat minor illnesses or provide preventive services, such as vaccines or flu shots. Among firms covering services in these settings, 17% provide a financial incentive to receive services in a retail clinic instead of a physician’s office.

OTHER TOPICS

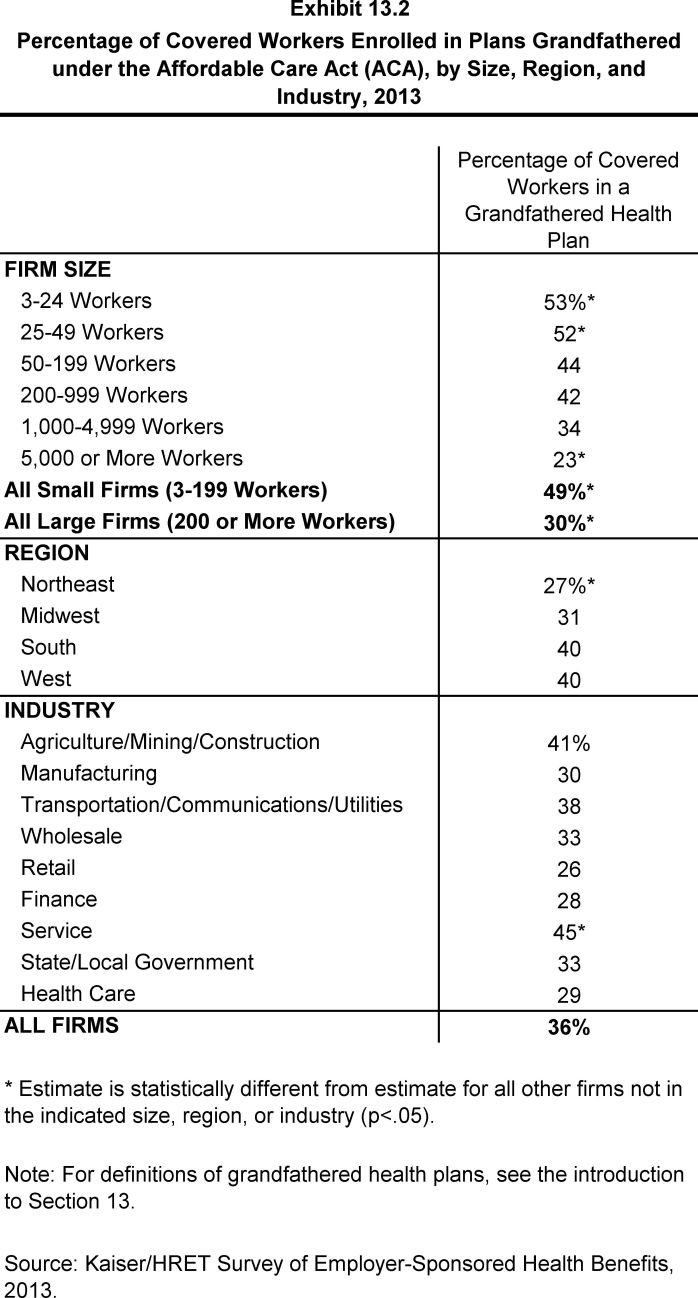

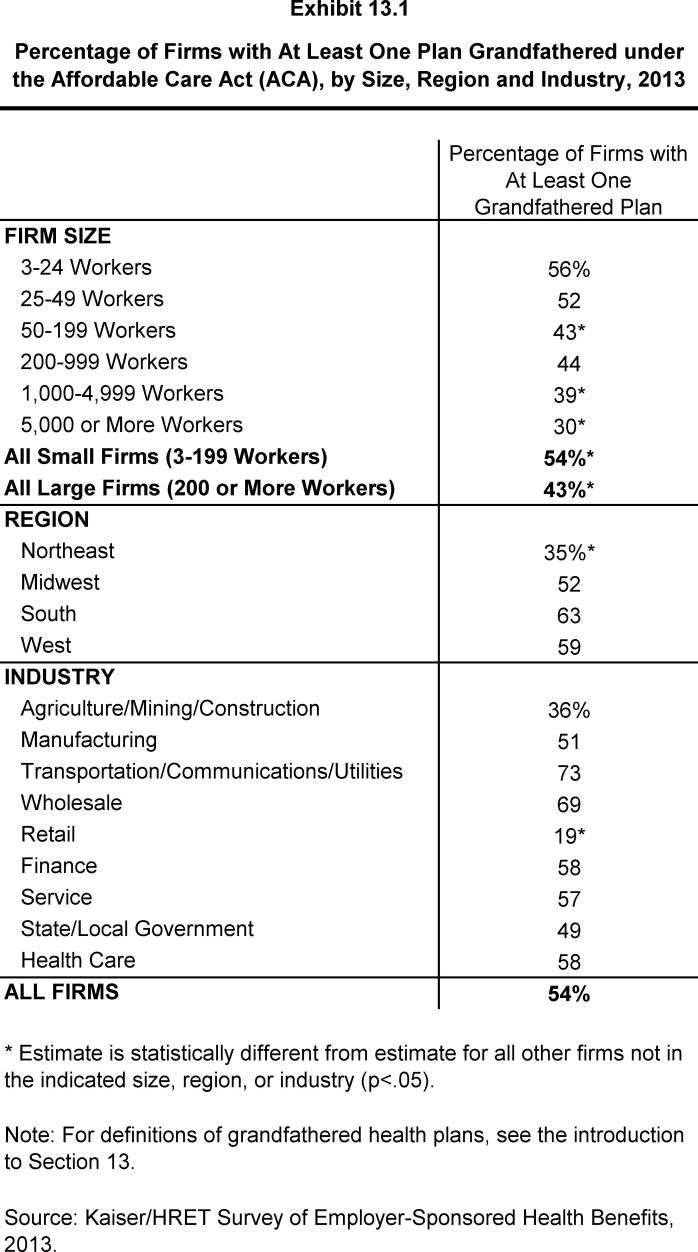

Grandfathered Health Plans. The ACA exempts “grandfathered” health plans from a number of its provisions, such as the requirements to cover preventive benefits without cost sharing or the new rules for small employers’ premiums ratings and benefits. An employer-sponsored health plan can be grandfathered if it covered a worker when the ACA became law (March 23, 2010) and if the plan has not made significant changes that reduce benefits or increase employee costs.3 Fifty-four percent of firms offering health benefits offer at least one grandfathered health plan in 2013, similar to the percentage reported in 2012. Small firms (3-199 workers) are more likely than larger firms to offer a grandfathered health plan (54% vs. 43%). Looking at enrollment, 36% of covered workers are enrolled in a grandfathered health plan in 2013, down from 48% in 2012 (Exhibit I). Covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) are more likely than covered workers in larger firms to be enrolled in a grandfathered health plan (49% vs. 30%).

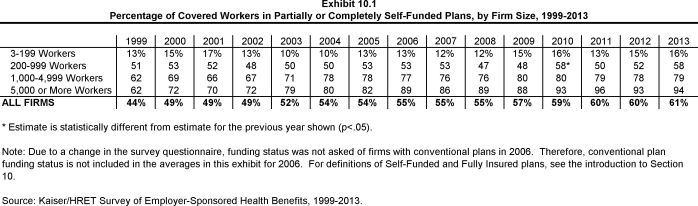

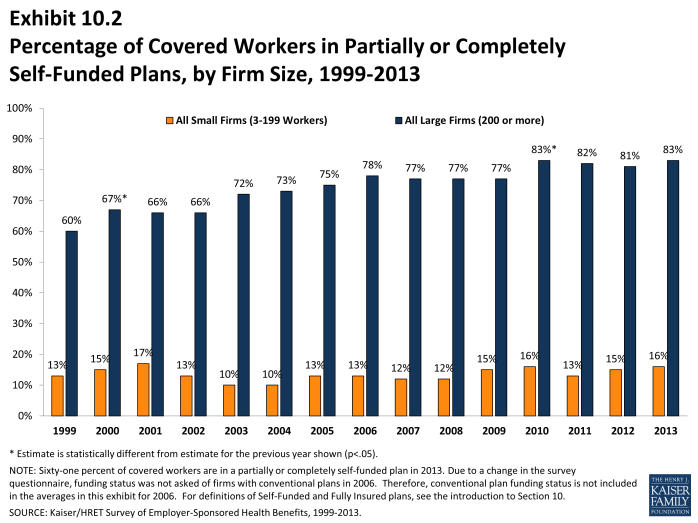

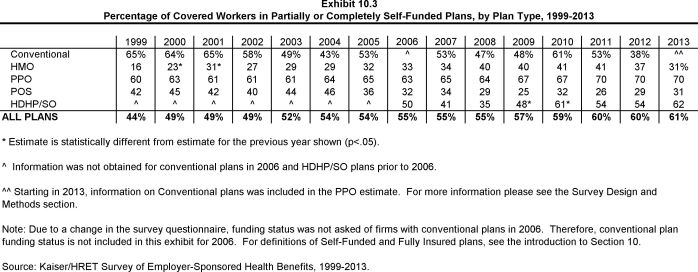

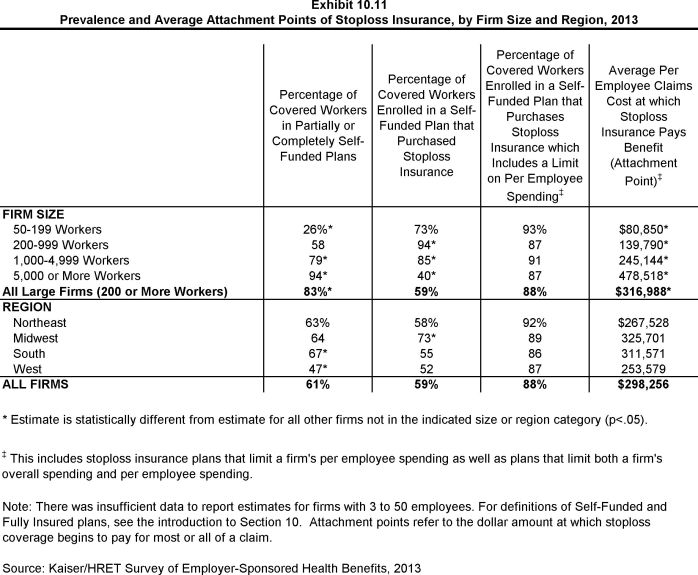

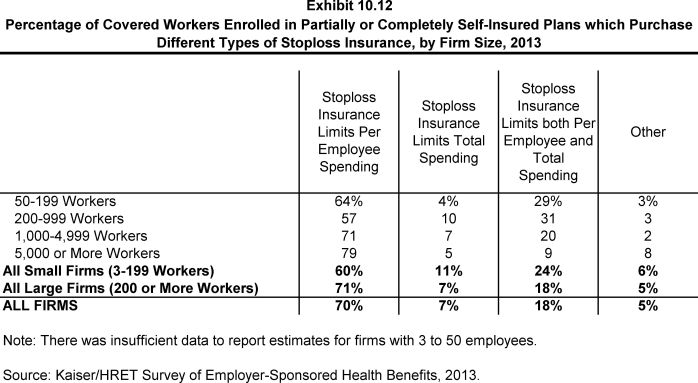

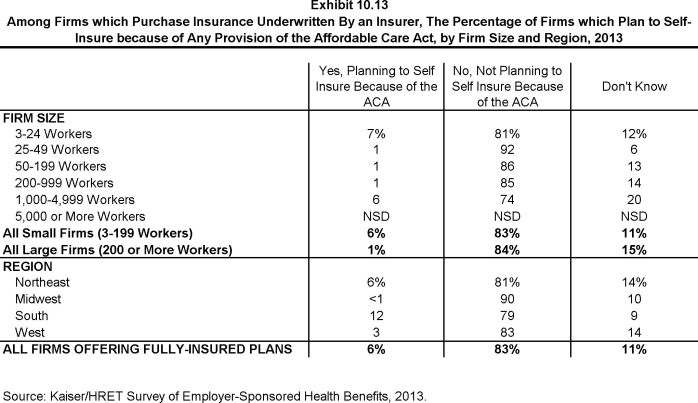

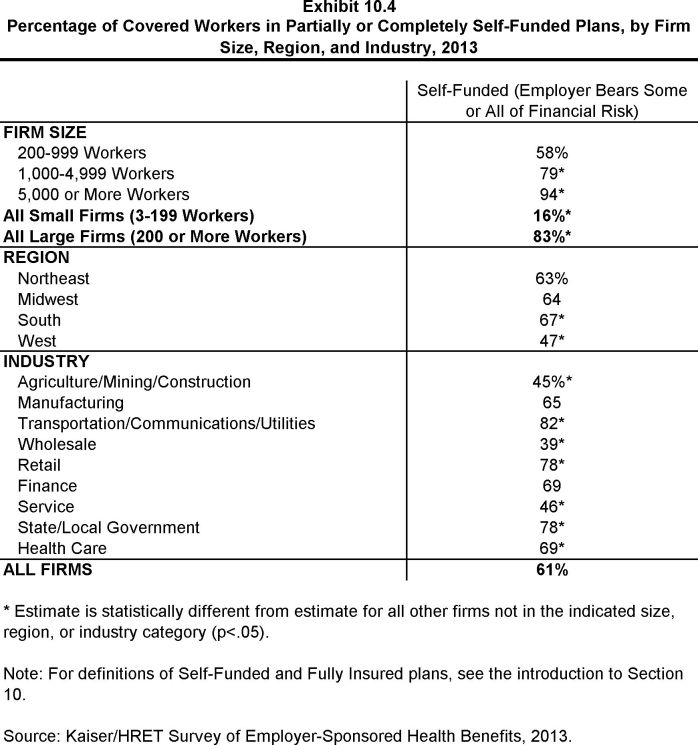

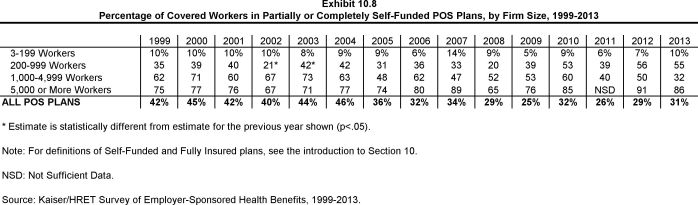

Self-Funding. Sixteen percent of covered workers at small firms (3-199 workers) and 83% of covered workers at larger firms are enrolled in plans which are either partially or completely self-funded, similar to 2012 (15% and 81%). Six percent of firms offering fully-insured plans report that they intend to self-insure because of the ACA.

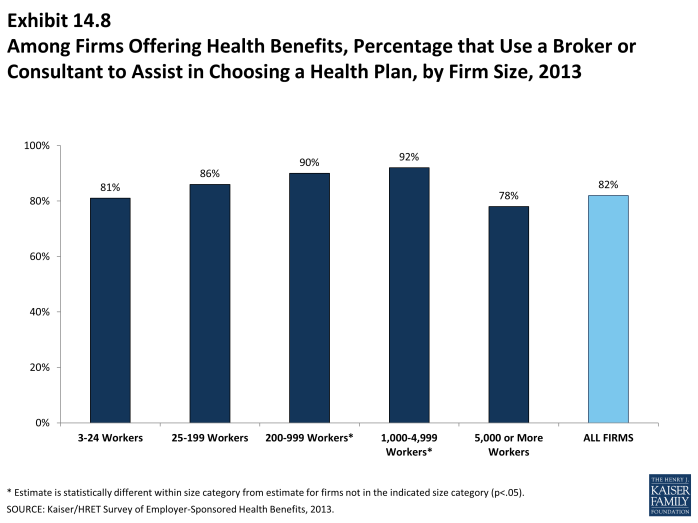

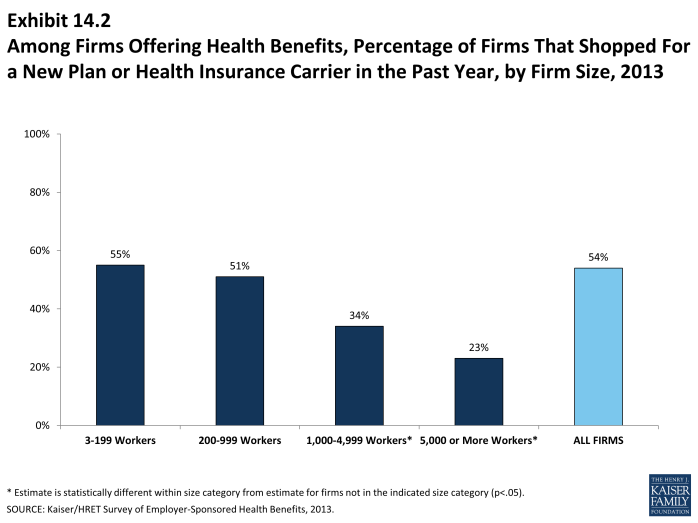

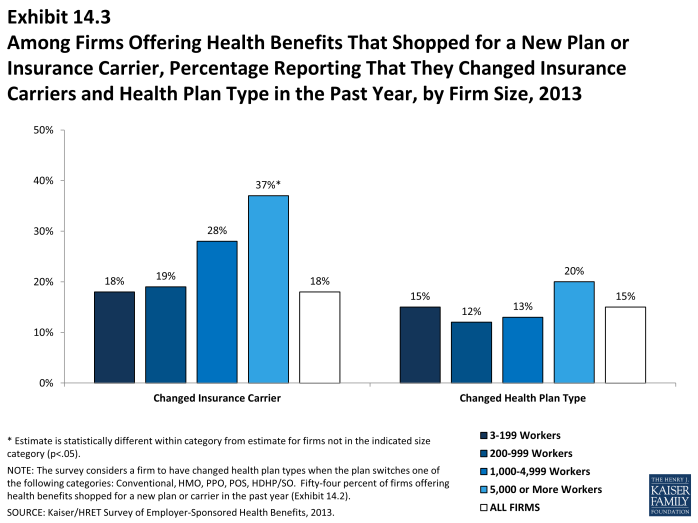

Shopping for Coverage. Fifty-four percent of firms shopped for a new health plan or insurance carrier in the previous year. There was not a significant difference between small (3 – 199 workers) and larger firms in the likelihood of shopping for new coverage. Among firms that shopped, 18% changed carriers in the past year and 15% changed the type of health plan (e.g., HMO, PPO, POS or HDHP/SO) that they offer.

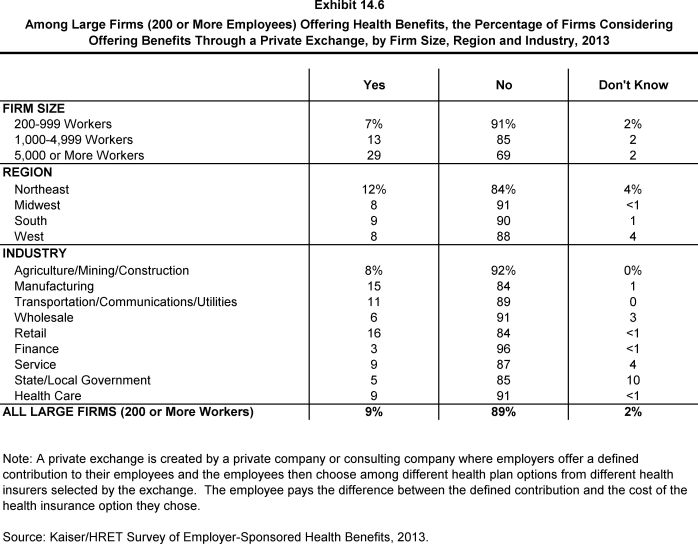

Exchanges for Large Employers. In the last two years, several consulting firms have announced that they were creating private exchanges for employers.4,5 These exchanges would provide employers an opportunity to give their employees a contribution that may be used to choose from a potentially broad choice of health plans that would be managed by the exchange. While few employers have adopted this approach to date, 9% of large firms (200 or more employees), including 29% of firms with 5,000 or more employees, reported that they are considering offering health benefits through a private exchange in the future. This interest may signal a significant change in the way that employers approach health benefits and the way employees get coverage, with employers playing a less active role in plan design and management.

CONCLUSION

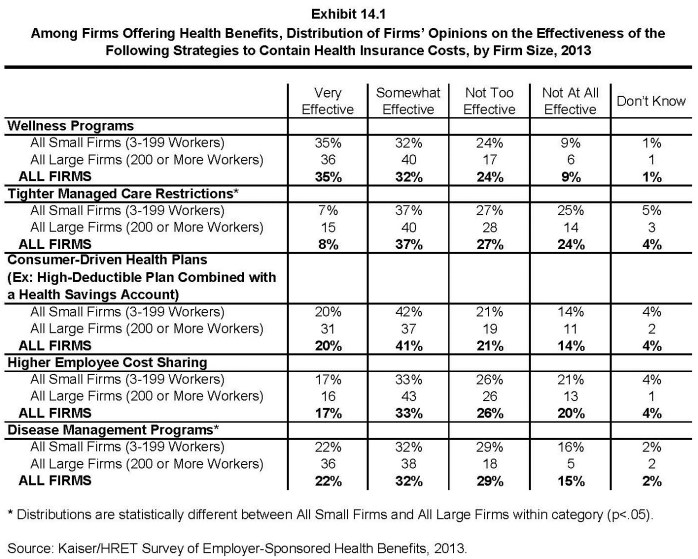

The 2013 annual survey did not find major changes in employer-based health benefits. Premiums increased at modest levels, consistent with the last several years, and coverage and offer rates did not change significantly. Employers remain committed to wellness programs: most covered workers are in plans with some type of wellness program and a majority (67%) of employers believes that wellness programs are very or somewhat effective in controlling health care costs.

More changes are expected over the next several years as many of more far-reaching provisions of the health reform law will take effect in 2014, including new benefits, cost-sharing tiers and premium rating rules that will apply to plans for employers with 50 or fewer workers. While several provisions affecting some larger employers have been delayed, most notably the requirement to offer coverage to all full-time employees by 2014, employers may begin adapting benefits and contributions to prepare to meet this requirement for 2015. The adoption of new federal rules for employee wellness programs, which permit employers to have larger financial rewards for employees who participate in wellness programs or who meet defined health outcomes, may encourage employers to modify or extend their wellness approaches.

The emergence of new exchanges, or marketplaces, also may portend important changes for employer-sponsored health insurance. Through an exchange, an employer can provide employees with a larger number and type of health plan options. Exchanges also facilitate the use of defined contributions or other strategies that encourage employees to choose lower cost plans or pay the difference in costs themselves. New SHOP exchanges will offer coverage options to small employers beginning in 2014, although employee choice will be limited in the federal SHOP exchanges until 2015. Large employers have the option of offering coverage through one of several exchanges being sponsored by benefit consulting organizations. While these approaches are new and differ across different exchanges, the common theme is to devolve some benefit choices, and some of the financial responsibility for those choices, to employees. Whether this new way of purchasing coverage works for employers and their employees, and how it affects benefits and plan costs, will be among the more important stories for the employer health insurance market over the next few years.

METHODOLOGY

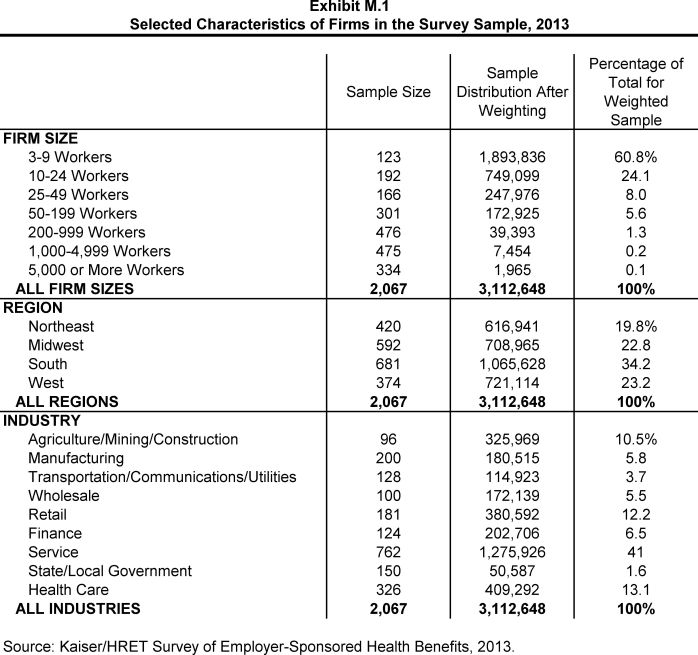

The Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research & Educational Trust 2013 Annual Employer Health Benefits Survey (Kaiser/HRET) reports findings from a telephone survey of 2,067 randomly selected public and private employers with three or more workers. Researchers at the Health Research & Educational Trust, NORC at the University of Chicago, and the Kaiser Family Foundation designed and analyzed the survey. National Research, LLC conducted the fieldwork between January and May 2013. In 2013 the overall response rate is 49%, which includes firms that offer and do not offer health benefits. Among firms that offer health benefits, the survey’s response rate is 50%.

We ask all firms with which we made phone contact, even if the firm declined to participate in the survey: “Does your company offer a health insurance program as a benefit to any of your employees?” A total of 2,948 firms responded to this question (including the 2,067 who responded to the full survey and 881 who responded to this one question). Their responses are included in our estimates of the percentage of firms offering health coverage. The response rate for this question is 70%.

Since firms are selected randomly, it is possible to extrapolate from the sample to national, regional, industry, and firm size estimates using statistical weights. In calculating weights, we first determine the basic weight, then apply a nonresponse adjustment, and finally apply a post-stratification adjustment. We use the U.S. Census Bureau’s Statistics of U.S. Businesses as the basis for the stratification and the post-stratification adjustment for firms in the private sector, and we use the Census of Governments as the basis for post-stratification for firms in the public sector. Some numbers in the exhibits in the report do not sum up to totals due to rounding effects, and, in a few cases, numbers from distribution exhibits referenced in the text may not add due to rounding effects. Unless otherwise noted, differences referred to in the text and exhibits use the 0.05 confidence level as the threshold for significance.

For more information on the survey methodology, please visit the Survey Design and Methods Section at http://ehbs.kff.org/.

The Kaiser Family Foundation, a leader in health policy analysis, health journalism and communication, is dedicated to filling the need for trusted, independent information on the major health issues facing our nation and its people. The Foundation is a non-profit private operating foundation, based in Menlo Park, California.

The Health Research & Educational Trust is a private, not-for-profit organization involved in research, education, and demonstration programs addressing health management and policy issues. Founded in 1944, HRET, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, collaborates with health care, government, academic, business, and community organizations across the United States to conduct research and disseminate findings that help shape the future of health care.

2013 Summary of Findings

exhibits

Average Annual Firm and Worker Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 2013

Distribution of Annual Premiums for Single and Family Coverage Relative to the Average Annual Single or Family Premium, 2013

Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 2013

Percentage of Covered Workers Enrolled in a Plan with a General Annual Deductible of $1,000 or More for Single Coverage, By Firm Size, 2006-2013

Report

Section One: Cost of Health Insurance

The average annual premiums in 2013 are $5,884 for single coverage and $16,351 for family coverage. Average premiums increased 5% for single coverage and 4% for family coverage in the last year. Family premiums have increased 80% since 2003 and have more than doubled since 2002. Average family premiums for workers in small firms (3-199 workers) ($15,581) are significantly lower than average family premiums for workers in larger firms (200 or more workers) ($16,715).

Premium Costs for Single and Family Coverage

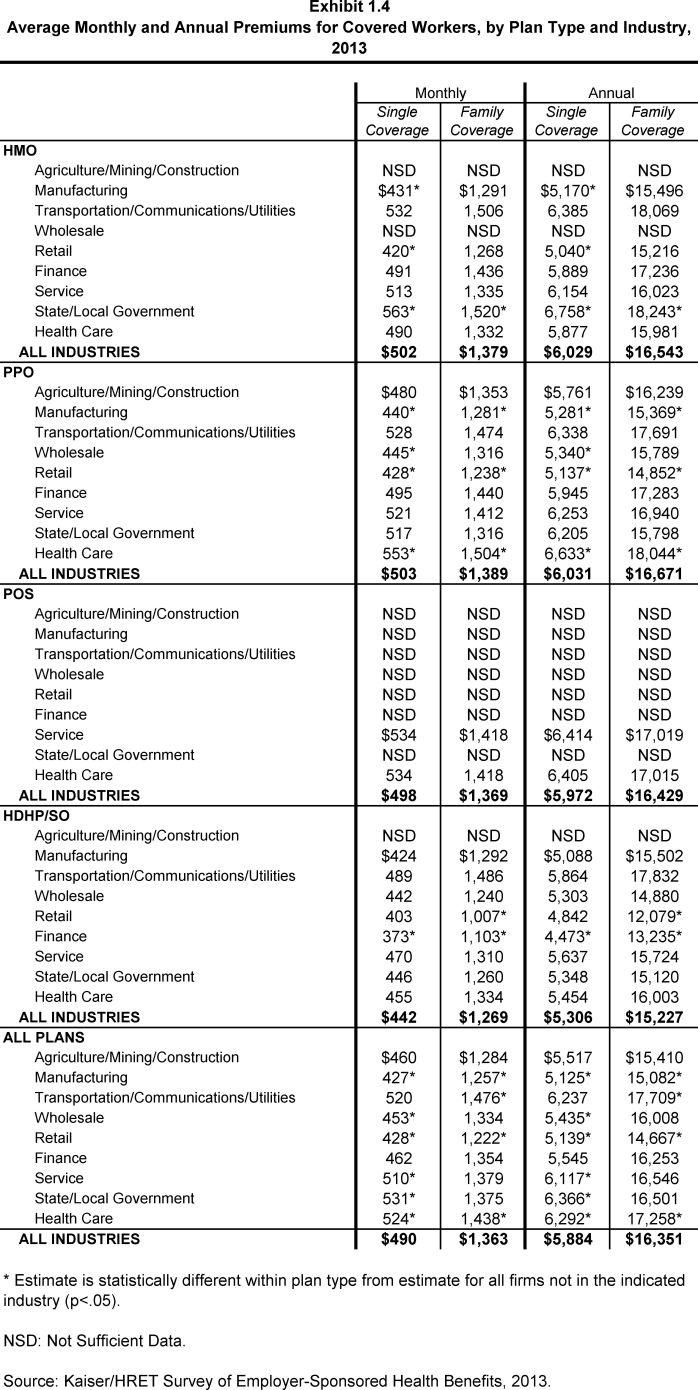

- The average premium for single coverage in 2013 is $490 per month or $5,884 per year (Exhibit 1.1). The average premium for family coverage is $1,363 per month or $16,351 per year (Exhibit 1.1).

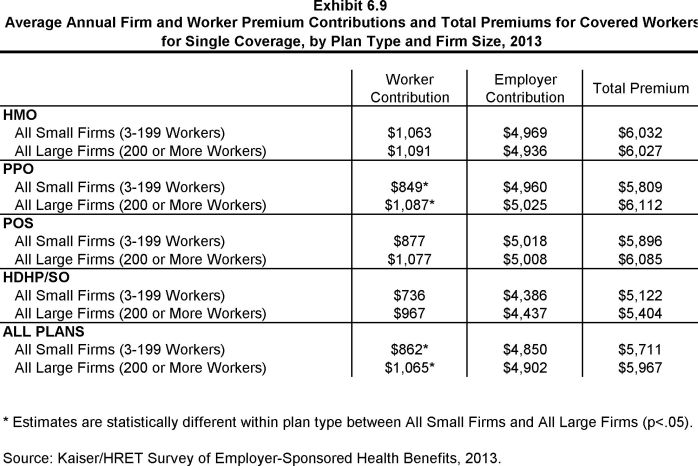

- The average annual premiums for covered workers in HDHP/SOs are lower for single ($5,306) and family coverage ($15,227) than the overall average premiums for covered workers. Average annual premiums for all other plan types, including PPO plans, HMOs, and POS plans, are similar to the overall average premiums for covered workers (Exhibit 1.1).

- The average premium for family coverage for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) ($15,581) is lower than the average premium for covered workers in large firms (200 or more workers) ($16,715) (Exhibit 1.2). The average single premium for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) and larger firms do not differ significantly.

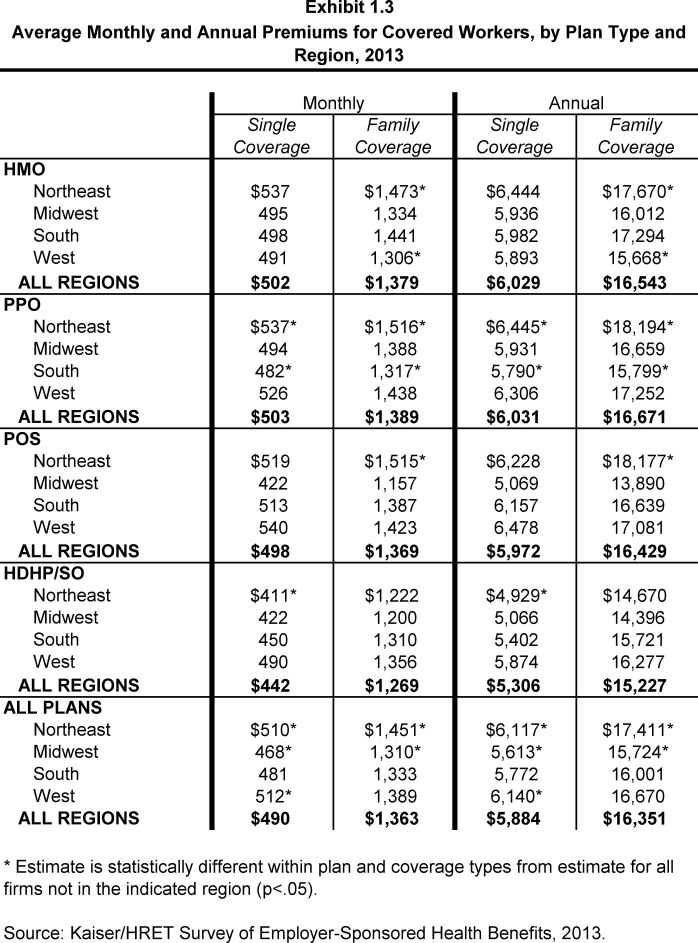

- Average single and family premiums for covered workers are higher in the Northeast ($6,117 and $17,411) and lower in the Midwest ($5,613 and $15,724) than the average premiums for covered workers in all other regions (Exhibit 1.3). Covered workers in the West also face higher premiums for single coverage ($6,140).

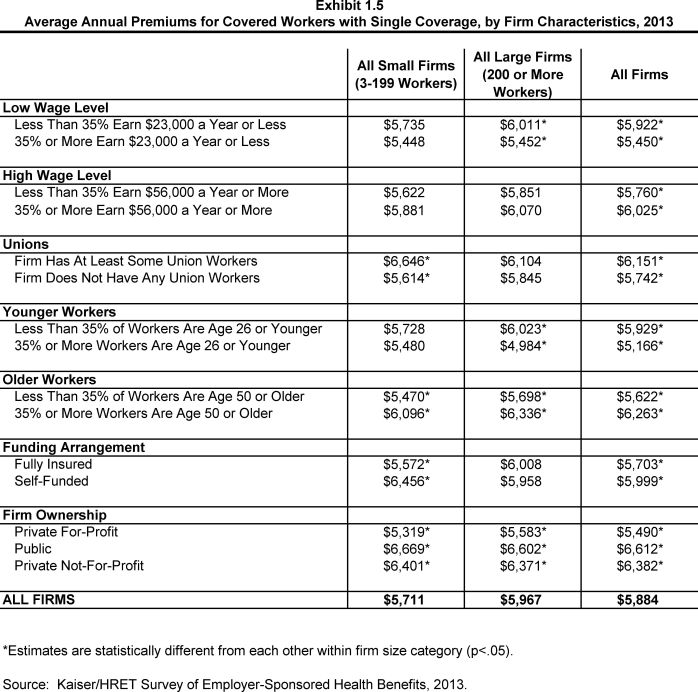

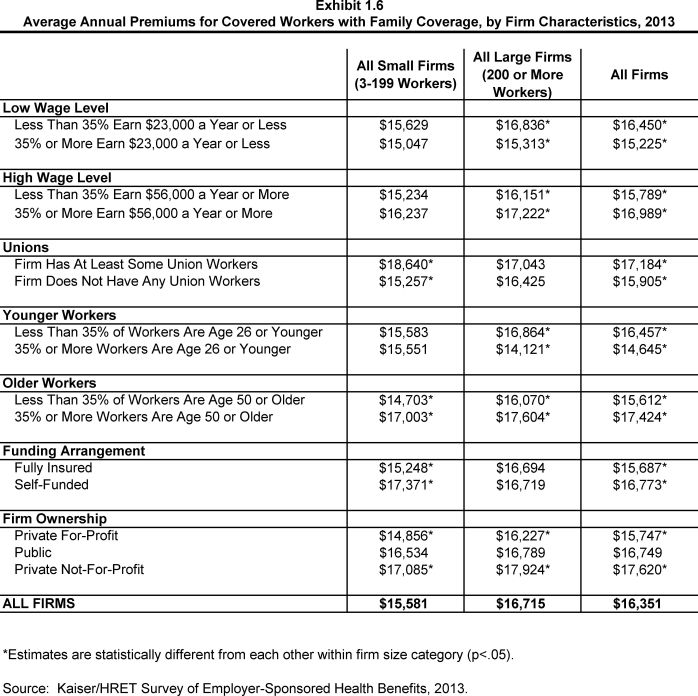

- Covered workers in firms where 35% or more of the workers are age 26 or younger have lower average single and family premiums ($5,166 and $14,645) than covered workers in firms where a lower percentage of workers are age 26 or younger ($5,929 and $16,457). Covered workers in firms where 35% or more of the workers are age 50 or older have higher average single and family premiums ($6,263 and $17,424) than covered workers in firms where a lower percentage of workers are age 50 or older ($5,622 and $15,612) (Exhibit 1.5) and (Exhibit 1.6).

- Covered workers in firms with a large percentage of lower-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $23,000 per year or less) have lower average single and family premiums ($5,450 and $15,225) than covered workers in firms with a smaller percentage of lower-wage workers ($5,922 and $16,450). Covered worker in firms with a large percentage of higher-wage workers (at least 35% of workers earn $56,000 per year or more) have higher average single and family premiums ($6,025 and $16,989) than covered workers in firms with a smaller percentage of higher-wage workers ($5,760 and $15,789) (Exhibit 1.5).

- There is considerable variation in premiums for both single and family coverage.

- Twenty-one percent of covered workers are employed by firms that have a single premium at least 20% higher than the average single premium, while 22% of covered workers are in firms that have a single premium less than 80% of the average single premium (Exhibit 1.7).

- For family coverage, 21% of covered workers are employed in a firm that has a family premium at least 20% higher than the average family premium, and another 21% of covered workers are in firms that have a family premium less than 80% of the average family premium (Exhibit 1.7) and (Exhibit 1.8).

Premium Changes Over Time

- The average annual single premium ($5,884) in 2013 is 5% higher than the average annual single premium in 2012 ($5,615), and the average annual family premium ($16,351) is 4% higher than the average annual family premium last year ($15,745) (Exhibit 1.11).

- The $16,351 average annual family premium in 2013 is 29% higher than the average family premium in 2008 and 80% higher than the average family premium in 2003 (Exhibit 1.11).

- Premiums for both small and large firms have seen a similar increase since 2008 (29%). For small firms (3 to 199 workers), the average family premium rose from $12,091 in 2008 to $15,581 in 2013. For large firms (200 or more workers), the average family premium rose from $12,973 in 2008 to $16,715 in 2013 (Exhibit 1.13).

- Since 2003, premiums for small firms (3 to 199 workers) have increased 74% ($15,581 in 2013 vs. $8,946 in 2003). The premiums for large firms have increased 83% ($16,715 in 2013 vs. $9,127 in 2003) (Exhibit 1.13).

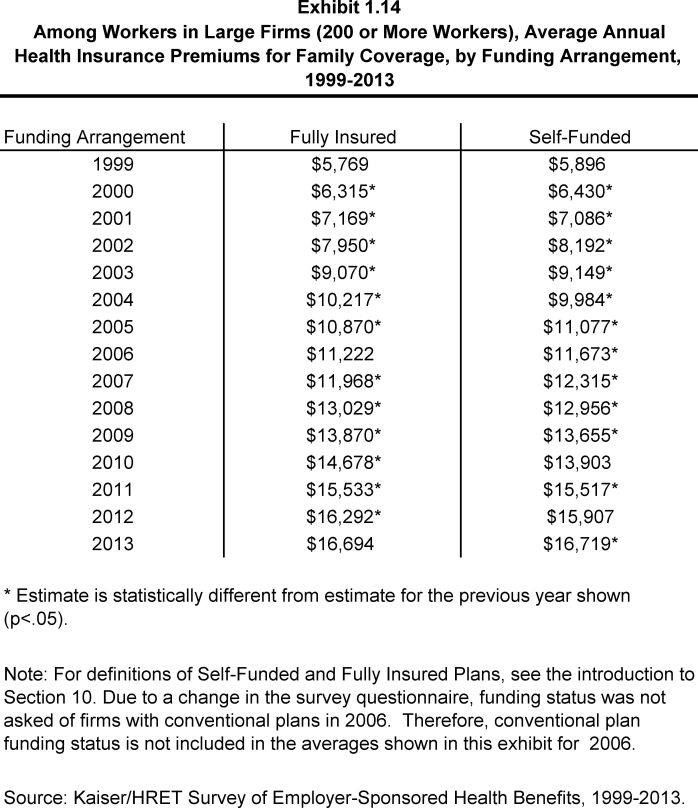

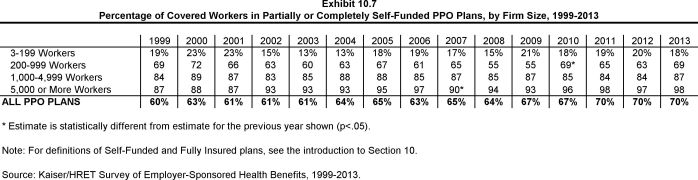

- For large firms (200 or more workers), the average family premium for covered workers in firms that are fully insured has grown at a similar rate to premiums for workers in fully or partially self-funded firms from 2008 to 2013 (28% in fully insured firms vs. 29% in self-funded firms) and from 2003 to 2013 (84% in fully insured firms vs. 83% in self-funded firms) (Exhibit 1.14).

Section One: Cost of Health Insurance

exhibits

Average Monthly and Annual Premiums for Covered Workers, Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 2013

Distribution of Annual Premiums for Single and Family Coverage Relative to the Average Annual Single or Family Premium, 2013

Distribution of Premiums for Single and Family Coverage Relative to the Average Annual Single or Family Premium, 2013

Section Two: Health Benefits Offer Rates

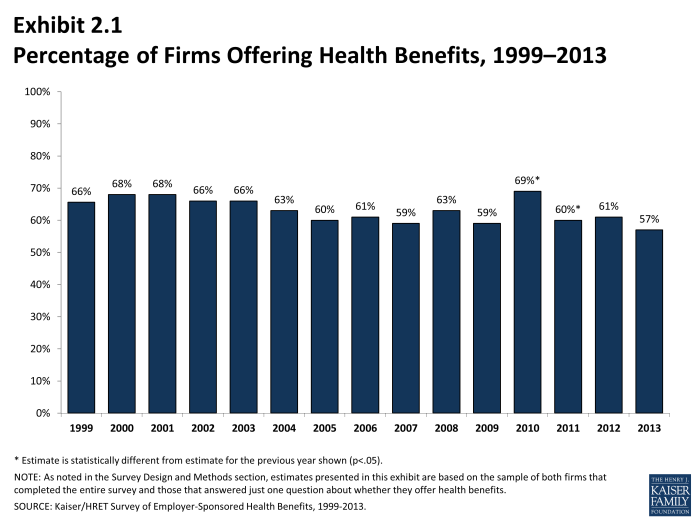

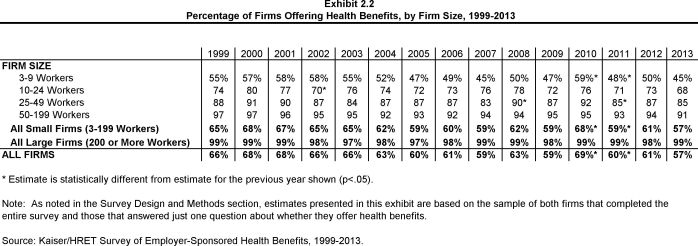

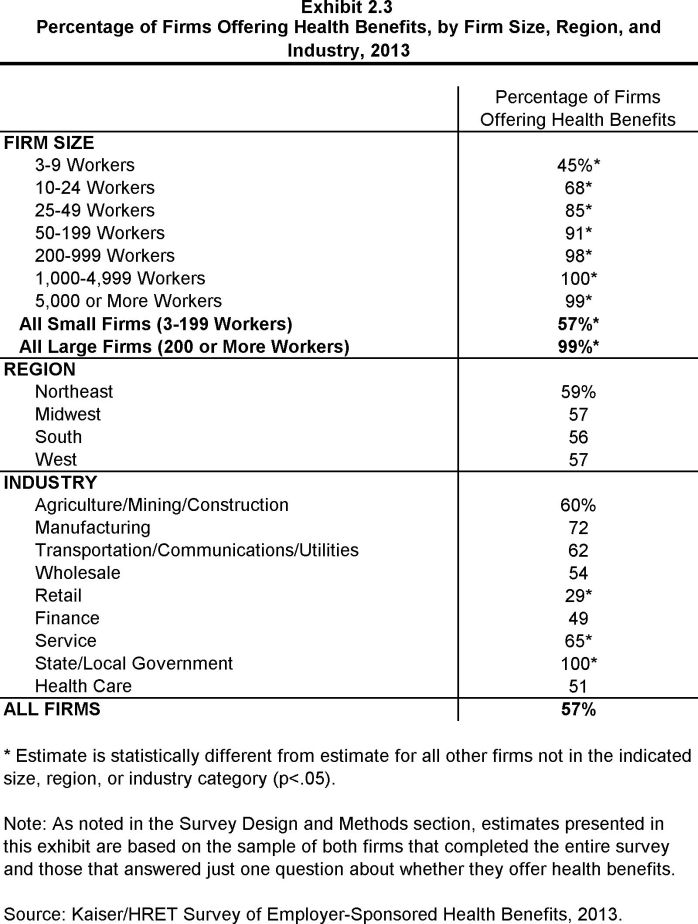

While nearly all large firms (200 or more workers) offer health benefits, small firms (3-199 workers) are significantly less likely to do so. The percentage of all firms offering health benefits in 2013 (57%) is statistically unchanged from 2012 and 2011 (61% and 60%).

- In 2013, 57% of firms offer health benefits, statistically unchanged from the 61% reported in 2012 (Exhibit 2.1).

- Similar to 2012, 99% of large firms (200 or more workers) offer health benefits to at least some of their workers (Exhibit 2.2). In contrast, only 57% of small firms (3-199 workers) offer health benefits in 2013.

- Between 1999 and 2013, the offer rate for large firms (200 or more workers) has consistently remained at or above 97%. Since most firms in the country are small, variation in the overall offer rate is driven primarily by changes in the percentages of the smallest firms (3-9 workers) offering health benefits.

- Offer rates vary across different types of firms.

- Smaller firms are less likely to offer health insurance: 45% of firms with 3 to 9 workers offer coverage, compared to 68% of firms with 10 to 24 workers, 85% of firms with 25 to 49 workers, and 91% of firms with 50 to 199 employees (Exhibit 2.3).

- Offering rates throughout different firm size categories in 2013 remained similar to those in 2012 (Exhibit 2.2).

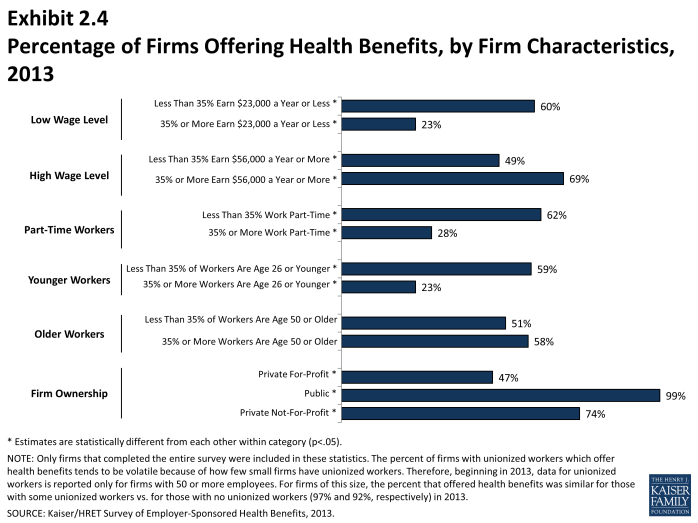

- Firms with fewer lower-wage workers (less than 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) are significantly more likely to offer health insurance than firms with many lower-wage workers (35% or more of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) (60% vs. 23%) (Exhibit 2.4). The offer rate for firms with many lower-wage workers is not significantly different from the 28% reported in 2012. We observe a similar pattern among firms with many higher-wage workers (35% or more of workers earn $56,000 or more annually) (Exhibit 2.4).

- The age of the workforce significantly affects the probability of a firm offering health benefits. Firms where 35% or more of its workers are age 26 or younger are less likely to offer health benefits than firms where less than 35% of workers are age 26 or younger (23% and 59%, respectively) (Exhibit 2.4).

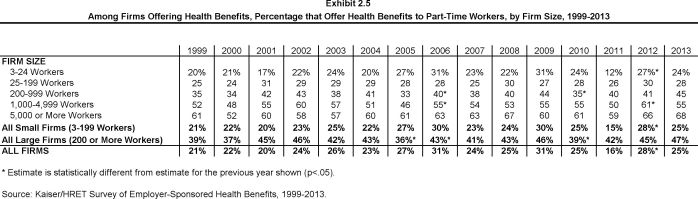

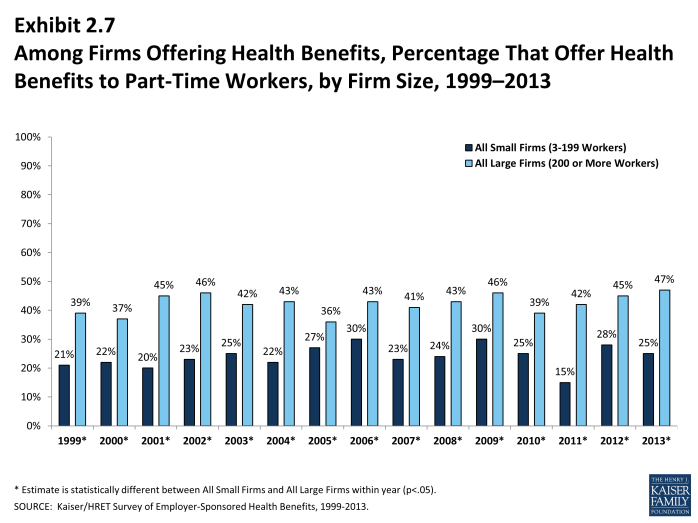

- Among firms offering health benefits, relatively few offer benefits to their part-time and temporary workers.

- In 2013, 25% of all firms that offer health benefits offer them to part-time workers, similar to the 28% reported in 2012 (Exhibit 2.5). Offering firms with 200 or more workers are more likely to offer health benefits to part-time employees than firms with 3 to 199 workers (47% vs. 25%) (Exhibit 2.7).

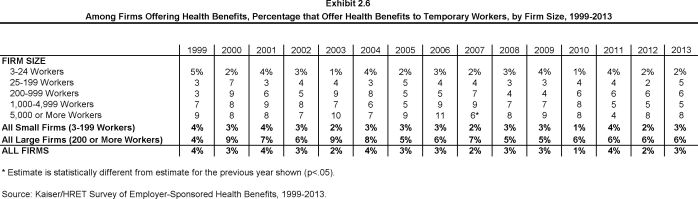

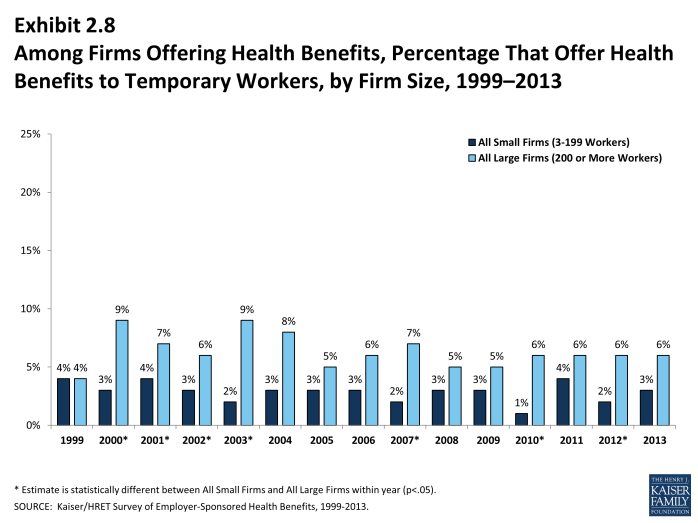

- Consistently, a very small percentage (3% in 2013) of firms offering health benefits have offered them to temporary workers (Exhibit 2.6). The percentage of firms offering temporary workers benefits is similar for small firms (3-199 workers) and large firms (200 or more workers) (3% vs. 6%) (Exhibit 2.8). The percentage of firms offering health benefits to temporary workers has been stable over time.

Firms Not Offering Health Benefits

- The survey asks firms that do not offer health benefits if they have offered insurance or shopped for insurance in the recent past, and about their most important reasons for not offering. Because such a small percentage of large firms report not offering health benefits, we present responses for smaller firms (3 to 199 workers) that do not offer health benefits.

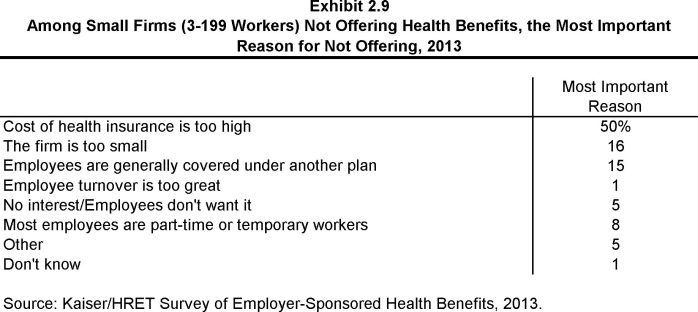

- The cost of health insurance remains the primary reason cited by firms for not offering health benefits. Among small firms (3-199 workers) not offering health benefits, 50% cite high cost as “the most important reason” for not doing so, followed by: “firm is too small” (16%) and “employees are generally covered under another plan” (15%) (Exhibit 2.9).

- Many non-offering, small firms have either offered health benefits in the past five years, or shopped for alternative coverage options recently.

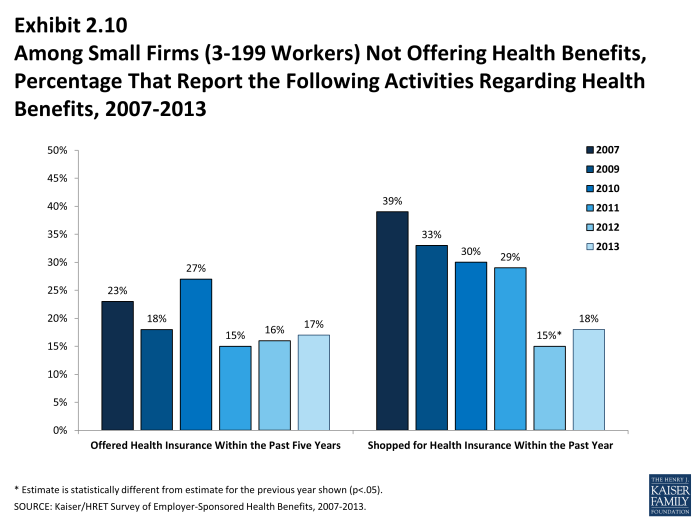

- Seventeen percent of non-offering, small firms (3-199 workers) have offered health benefits in the past five years, while 18% have shopped for coverage in the past year (Exhibit 2.10).

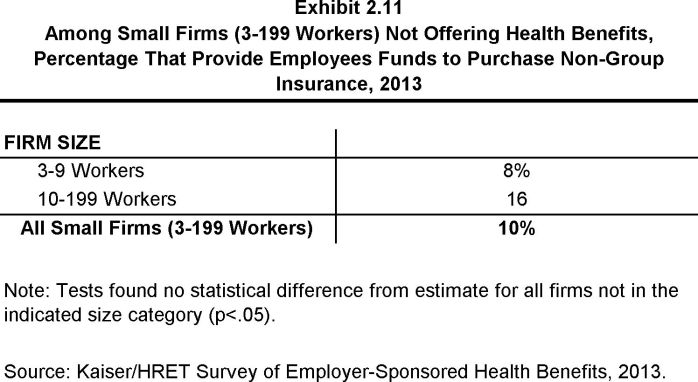

- Among non-offering, small firms (3-199 workers), 10% report that they provide funds to their employees to purchase health insurance through the individual (non-group) market (Exhibit 2.11).

Section Two: Health Benefits Offer Rates

exhibits

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage that Offer Health Benefits to Part-Time Workers, by Firm Size, 1999-2013

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage that Offer Health Benefits to Temporary Workers, by Firm Size, 1999-2013

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer Health Benefits to Part-Time Workers, by Firm Size, 1999–2013

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer Health Benefits to Temporary Workers, by Firm Size, 1999–2013

Among Small Firms (3-199 Workers) Not Offering Health Benefits, the Most Important Reason for Not Offering, 2013

Section Three: Employee Coverage, Eligibility, and Participation

Employers are the principal source of health insurance in the United States, providing health benefits for about 149 million nonelderly people in America.1 Most workers are offered health coverage at work, and the majority of workers who are offered coverage take it. Workers may not be covered by their own employer for several reasons: their employer may not offer coverage, they may be ineligible for benefits offered by their firm, they may choose to elect coverage through their spouse’s employer, or they may refuse coverage from their firm.

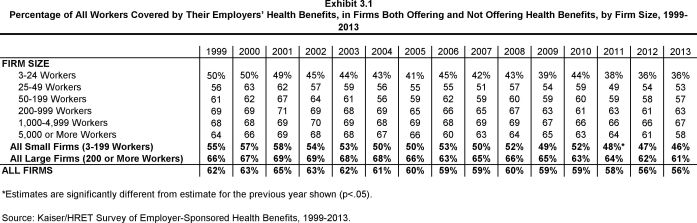

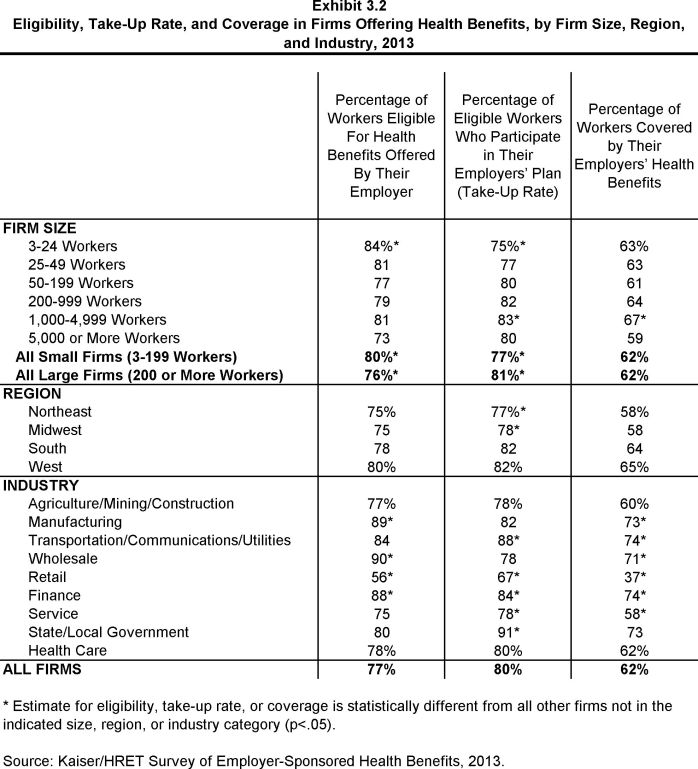

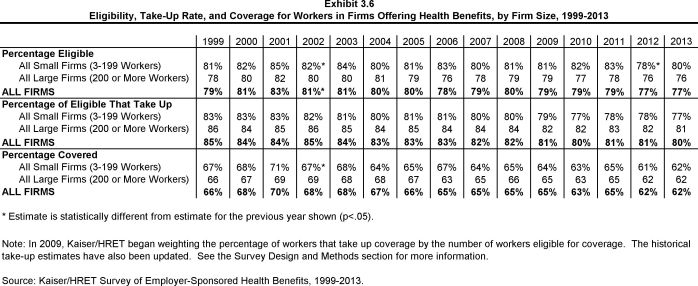

- Among firms offering health benefits, 62% percent of workers are covered by health benefits through their own employer (Exhibit 3.2). When considering both firms that offer health benefits and those that don’t, 56% of workers are covered under their employer’s plan (Exhibit 3.1). This coverage rate has remained stable over time.

Eligibility

- Not all employees are eligible for the health benefits offered by their firm, and not all eligible employees take up the offer of coverage. The share of workers covered in a firm is a product of both the percentage of workers who are eligible for the firm’s health insurance and the percentage who choose to “take up” (i.e., elect to participate in) the benefit.

- Seventy-seven percent of workers in firms offering health benefits are eligible for the coverage offered by their employer (Exhibit 3.2).

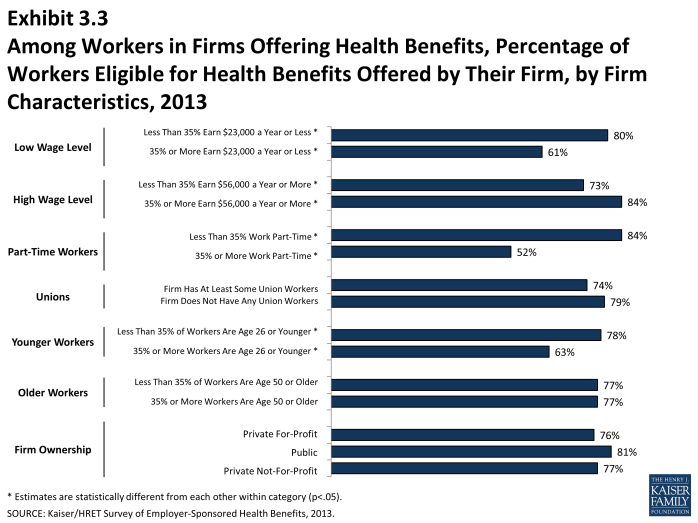

- Eligibility varies considerably by wage level. Employees in firms with a lower proportion of lower-wage workers (less than 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) are more likely to be eligible for health benefits than employees in firms with a higher proportion of lower-wage workers (80% vs. 61%). We observe a similar pattern among firms with many higher-wage workers (35% or more of workers earn $56,000 or more annually) (84% vs. 73%) (Exhibit 3.3).

- Eligibility also varies by the age of the workforce. Those in firms with fewer younger workers (less than 35% of workers are age 26 or younger) are more likely to be eligible for health benefits than are workers in firms with many younger workers, at 78% versus 63% (Exhibit 3.3).

Take-up Rate

- Employees who are offered health benefits generally elect to take up the coverage. In 2013, 80% of eligible workers take up coverage when it is offered to them, which is similar to the 81% reported last year (Exhibit 3.2).2

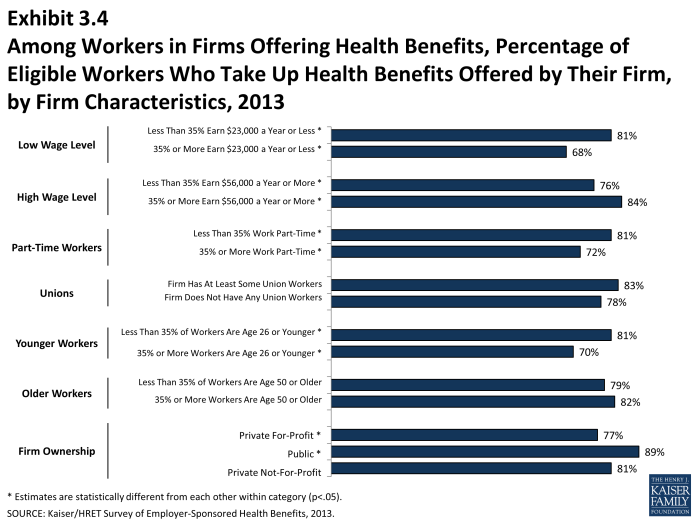

- The likelihood of a worker accepting a firm’s offer of coverage also varies by workforce wage level. Eligible employees in firms with a lower proportion of lower-wage workers are more likely to take up coverage (81%) than eligible employees in firms with a higher proportion of lower-wage workers (35% or more of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) (68%) (Exhibit 3.4). Similar patterns are seen in firms with a higher proportion of younger workers, with workers in these firms being less likely to take up coverage than those in firms with a smaller share of younger workers (70% vs. 81%).

- Almost nine out of ten workers at public employers who offer health benefits take up coverage (89%). However, workers at private for-profit employers are significantly less likely to do so – only 77% of these workers take up coverage (Exhibit 3.4).

Coverage

- There is significant variation by industry in the coverage rate among workers in firms offering health benefits. For example, only 37% of workers in retail firms offering health benefits are covered by the health benefits offered by their firm, compared to 74% of workers in finance, and 74% of workers in the transportation/communications/utilities industry category (Exhibit 3.2).

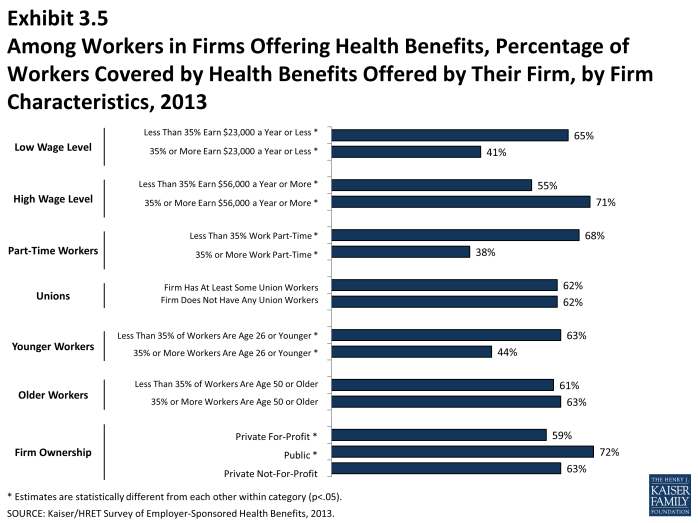

- Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with relatively few part-time workers (less than 35% of workers are part-time) are much more likely to be covered by their own firm than workers in firms with a greater percentage of part-time workers (68% vs. 38%) (Exhibit 3.5).

- Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with fewer lower-wage workers (less than 35% of workers earn $23,000 or less annually) are more likely to be covered by their own firm than workers in firms with many lower-wage workers (65% vs. 41%) (Exhibit 3.5). A comparable pattern exists in firms with a larger proportion of higher wage workers (35% or more earn $56,000 or more annually) offering health benefits.

- Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with fewer younger workers (less than 35% of workers are age 26 or younger) are more likely to be covered by their own firm than workers in firms with many younger workers (63% vs. 44%) (Exhibit 3.5).

Average Waiting Periods

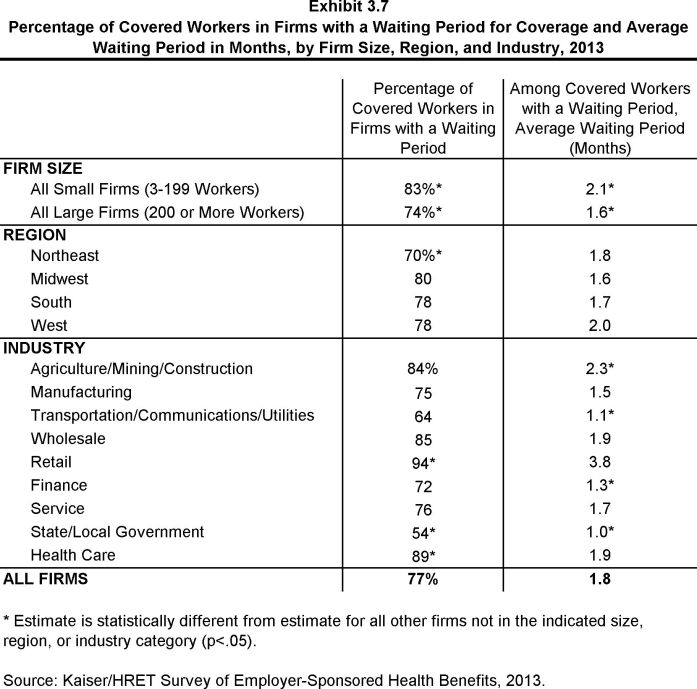

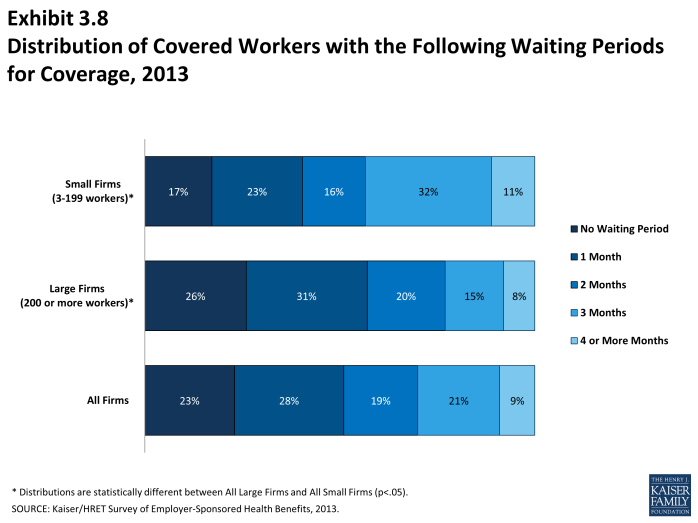

- Seventy-seven percent of covered workers face a waiting period before coverage is available. Covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) are more likely than those in large firms to have a waiting period, at 83% versus 74% (Exhibit 3.7). Workers in the Northeast are less likely to face a wait for coverage than all other regions (70%).

- The average waiting period among covered workers who face a waiting period is 1.8 months (Exhibit 3.7). While 30% of covered workers face a waiting period of 3 months or more, only 9% face a waiting period of 4 months or more. Workers in small firms (3-199 workers) generally have longer waiting periods than workers in larger firms (Exhibit 3.8).

- Ninety-one percent of covered workers at firms with many lower wage workers (firms where more than 35% of the workforce makes $23,000 or less) compared to 76% at firms with few lower-wage workers face a waiting period before coverage is available.

Section Three: Employee Coverage, Eligibility, and Participation

exhibits

Percentage of All Workers Covered by Their Employers’ Health Benefits, in Firms Both Offering and Not Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2013

Eligibility, Take-Up Rate, and Coverage in Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, Region, and Industry, 2013

Among Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Workers Eligible for Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2013

Among Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Eligible Workers Who Take Up Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2013

Among Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Workers Covered by Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2013

Eligibility, Take-Up Rate, and Coverage for Workers in Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2013

Section Four: Types of Plans Offered

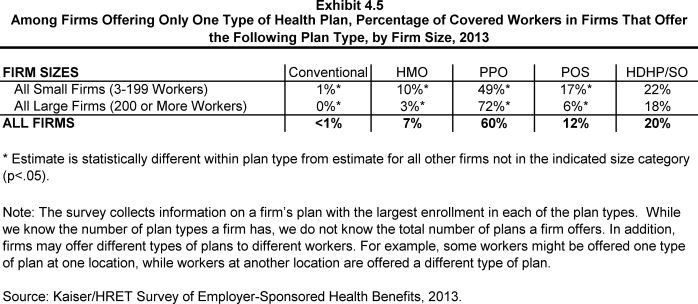

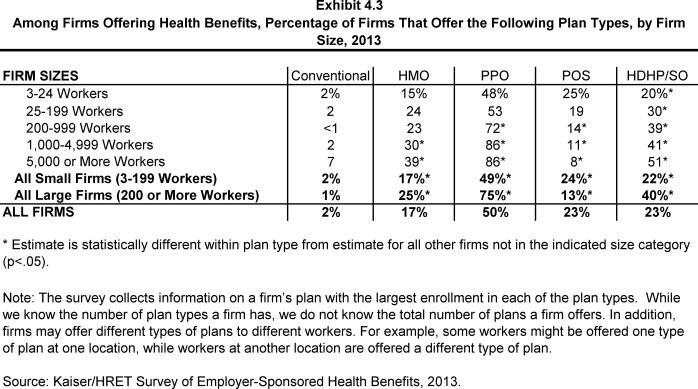

Most firms that offer health benefits offer only one type of health plan (82%) (See Text Box). Larger firms are more likely to offer more than one type of health plan. Employers are most likely to offer their workers a PPO, HMO, or HDHP/SO plan and are least likely to offer a conventional plan.

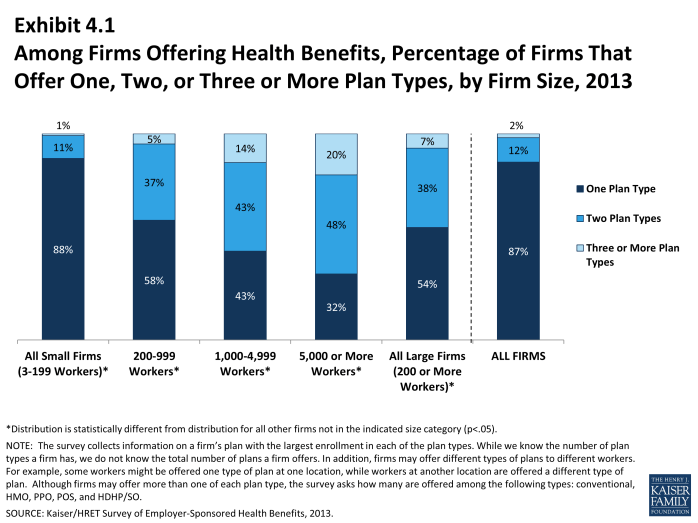

- Eighty-two percent of firms offering health benefits in 2012 offer only one type of health plan. Large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to offer more than one plan type than small firms (3-199 workers): 45% vs. 17% (Exhibit 4.1).

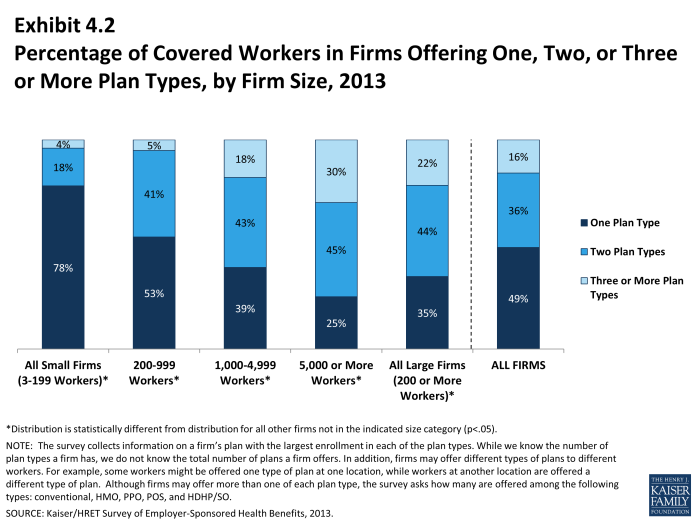

- Over half (52%) of covered workers are employed in a firm that offers more than one health plan type. Sixty-five percent of covered workers in large firms (200 or more workers) are employed by a firm that offers more than one plan type, compared to 26% in small firms (3-199 workers) (Exhibit 4.2).

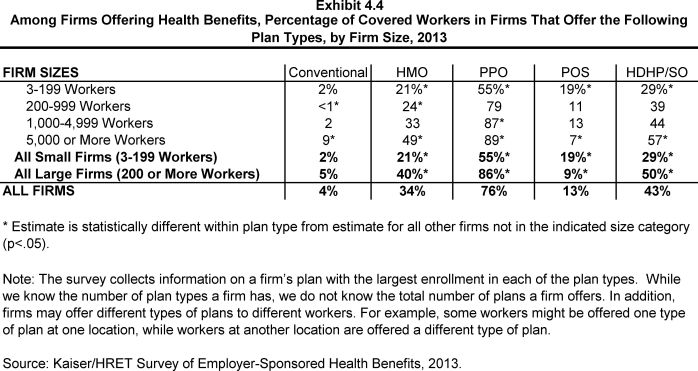

- Three quarters (75%) of covered workers in firms offering health benefits work in a firm that offers one or more PPOs; 39% work in firms that offer one or more HDHP/SOs; 37% work in firms that offer one or more HMOs; 14% work in firms that offer one or more POS plans; and 4% work in firms that offer one or more conventional plans (Exhibit 4.4).1

The survey collects information on a firm’s plan with the largest enrollment in each of the plan types. While we know the number of plan types a firm has, we do not know the total number of plans a firm offers. In addition, firms may offer different types of plans to different workers. For example, some workers might be offered one type of plan at one location, while workers at another location are offered a different type of plan.

Section Four: Types of Plans Offered

exhibits

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Offer One, Two, or Three or More Plan Types, by Firm Size, 2013

Percentage of Covered Workers in Firms Offering One, Two, or Three or More Plan Types, by Firm Size, 2013

Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Offer the Following Plan Types, by Firm Size, 2013

Section Five: Market Shares of Health Plans

Enrollment remains highest in PPO plans, covering more than half of covered workers, followed by HDHP/SOs, HMO plans, POS plans, and conventional plans. Enrollment distribution varies by firm size, for example, PPOs are relatively more popular for covered workers at large firms (200 or more workers) than smaller firms (62% vs. 47%) and POS plans are relatively more popular among smaller firms than large firms (16% vs. 5%) (Exhibit 5.2).

- Fifty-seven percent of covered workers are enrolled in PPOs, followed by HDHP/SOs (20%), HMOs (14%), POS plans (9%), and conventional plans (<1%) (Exhibit 5.1).

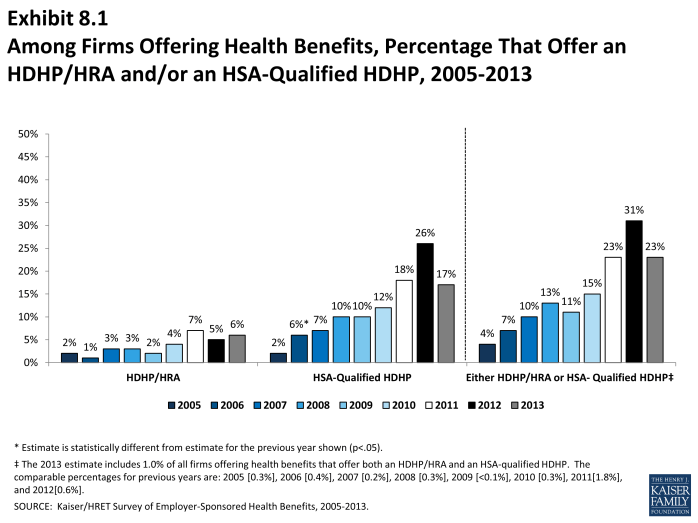

- After years of significant annual increases in the percentage of covered workers enrolled in HDHP/SO plans (8% in 2009, 13% in 2010, and 17% in 2011), there has been a similar level of enrollment over the past two years (19% in 2012 and 20% in 2013) (Exhibit 5.1).

- Enrollment in HMO plans is similar to 2012, but has declined significantly since 2011.

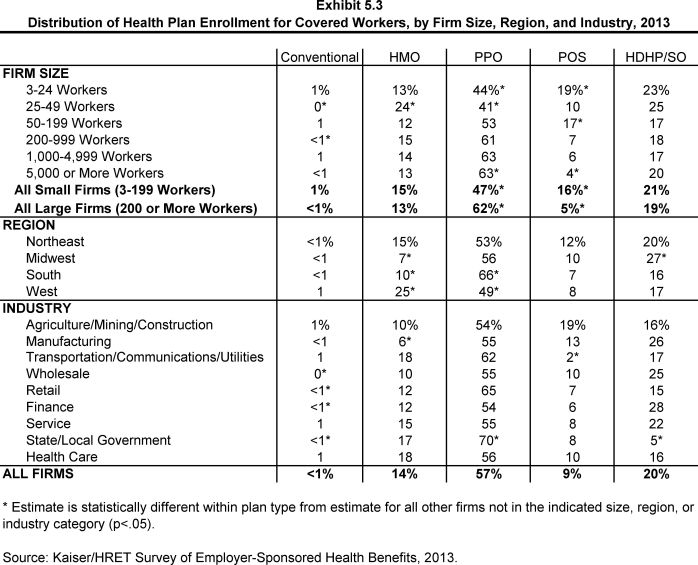

- Plan enrollment patterns vary by firm size. Workers in large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely than workers in small firms (3-199 workers) to enroll in PPOs (62% vs. 47%). Workers in small firms are more likely than workers in large firms to enroll in POS plans (16% vs. 5%) (Exhibit 5.3).

- Plan enrollment patterns also differ across regions.

- HMO enrollment is significantly higher in the West (25%) and significantly lower in the South (10%) and Midwest (7%) (Exhibit 5.3).

- Workers in the South (66%) are more likely to be enrolled in PPO plans than workers in other regions; workers in the West (49%) are less likely to be enrolled in a PPO (Exhibit 5.3).

- Enrollment in HDHP/SOs is higher among workers in the Midwest (27%) than in other regions (Exhibit 5.3).

Section Five: Market Shares of Health Plans

exhibits

Section Six: Worker and Employer Contributions for Premiums

Premium contributions by covered workers average 18% for single coverage and 29% for family coverage.1 The average monthly worker contributions are $83 for single coverage ($999 annually) and $380 for family coverage ($4,565 annually). These percentage and dollar values are similar to the values reported in 2012.

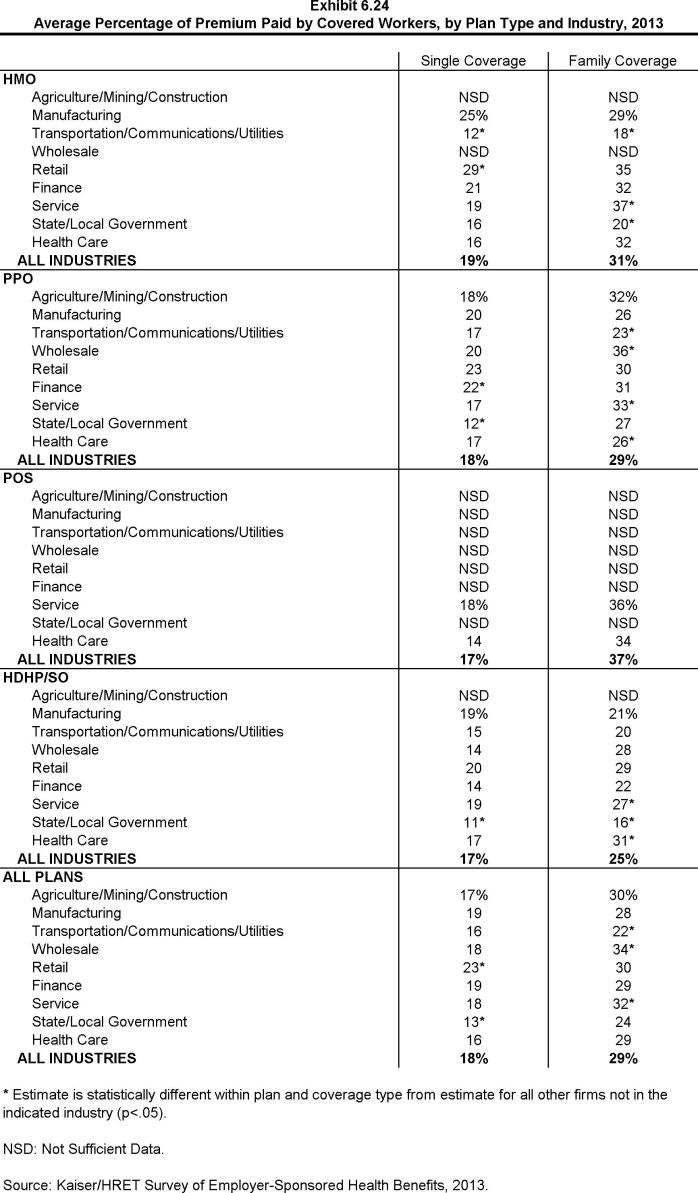

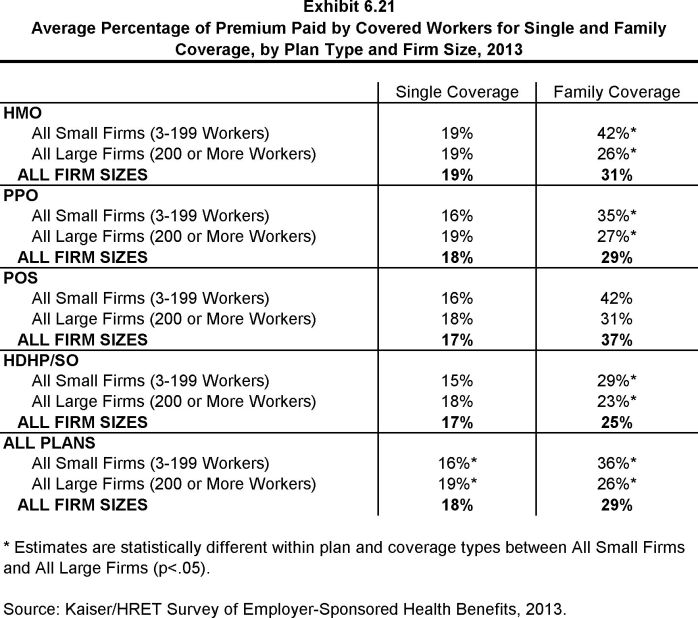

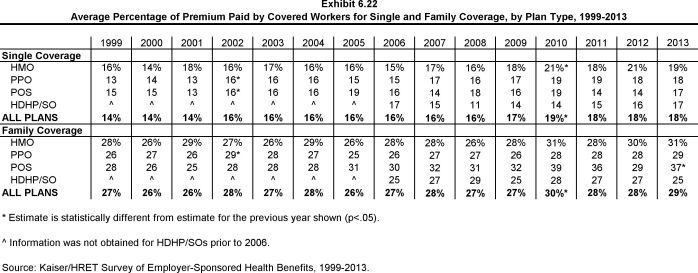

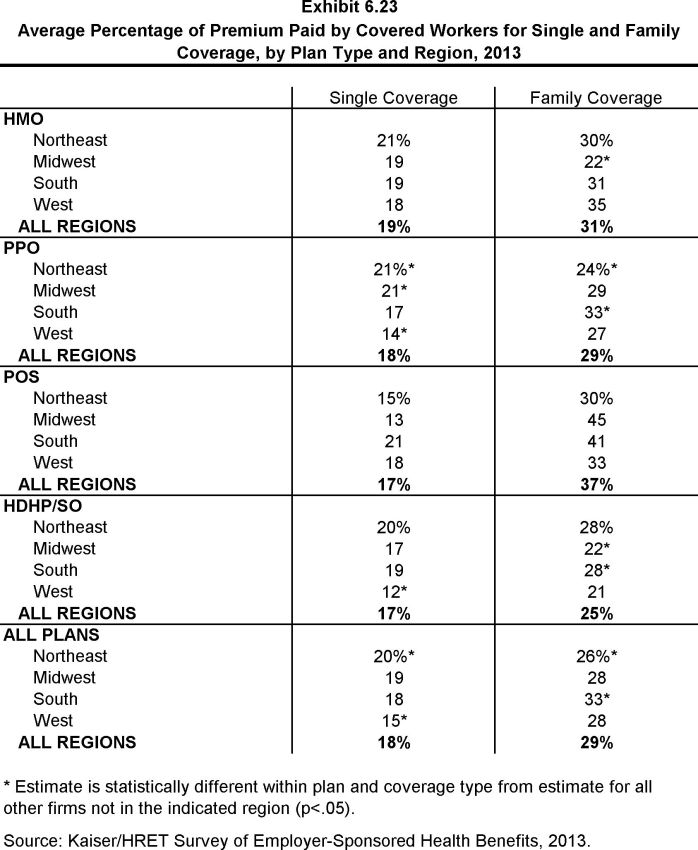

- In 2013, covered workers on average contribute 18% of the premium for single coverage and 29% of the premium for family coverage, similar to the contribution percentages reported for 2012 (Exhibit 6.1). The premium contributions have remained stable over the last three years for both single and family coverage.

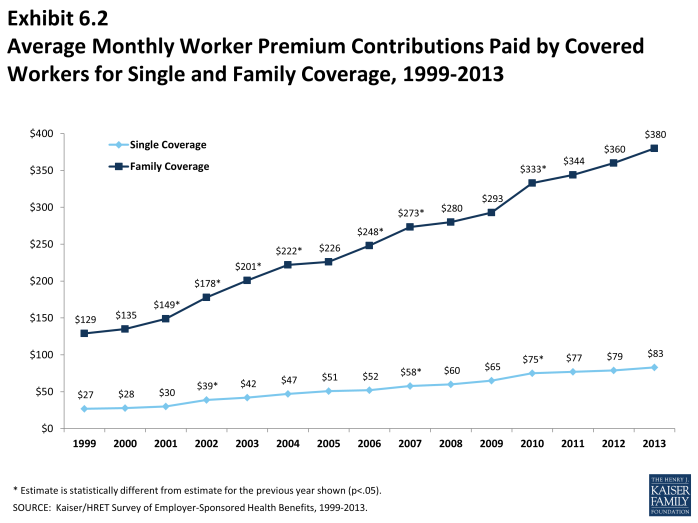

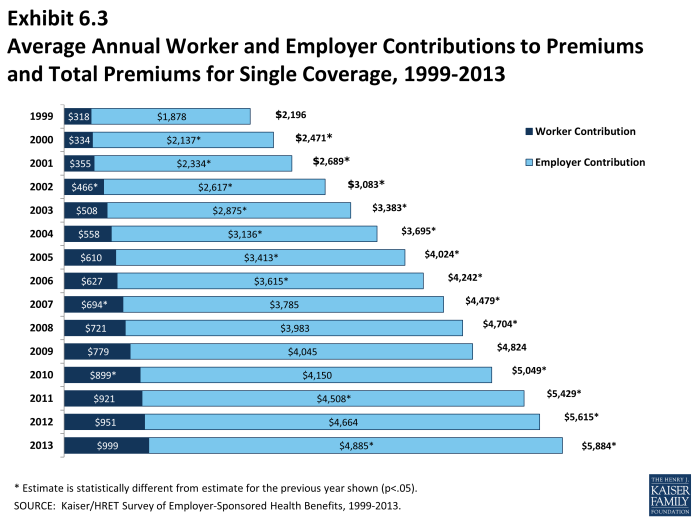

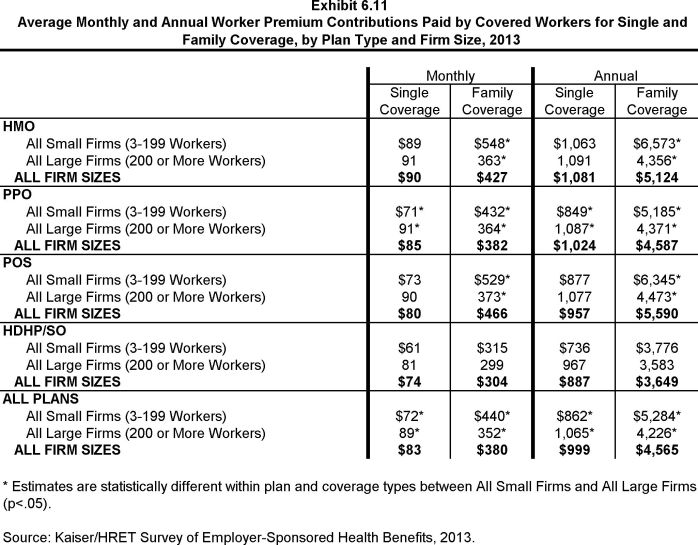

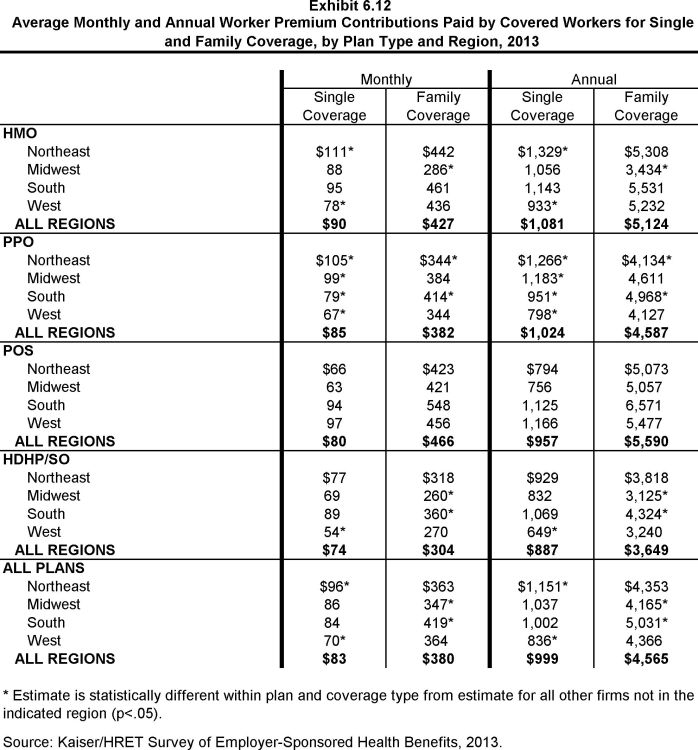

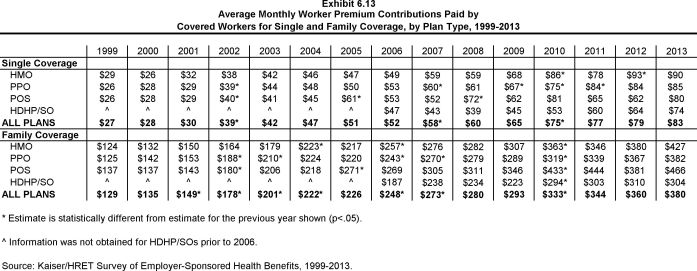

- On average, workers with single coverage contribute $83 per month ($999 annually), and workers with family coverage contribute $380 per month ($4,565 annually), towards their health insurance premiums, similar to the amounts reported in 2012 (Exhibit 6.2), (Exhibit 6.3), and (Exhibit 6.4).

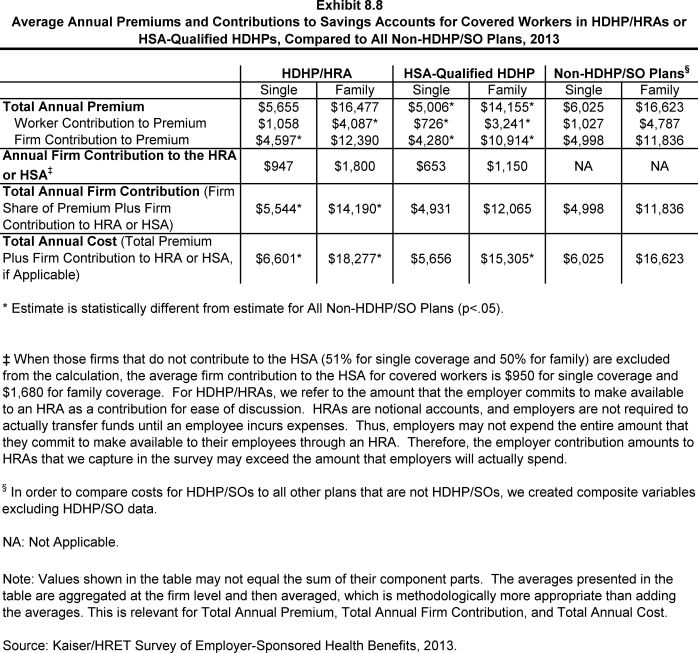

- Worker contributions in HDHP/SOs are lower than the overall average worker contributions for family coverage ($3,649 vs. $4,565) (Exhibit 6.5). Similarly, covered workers enrolled in HDHP/SO plans contribute less on average for family coverage than covered workers enrolled in other plan types ($3,649 vs. $4,787).

- Worker contributions in POS plans are higher for family coverage ($5,590) compared to the overall worker contribution for family coverage (Exhibit 6.5).

- In addition to differences between plan types, there are differences in worker contributions by type of firm. As in previous years, workers in small firms (3-199 workers) contribute a lower amount annually for single coverage than workers in large firms (200 or more workers), $862 vs. $1,065. In contrast, workers in small firms with family coverage contribute significantly more annually than workers with family coverage in large firms ($5,284 vs. $4,226) (Exhibit 6.8).

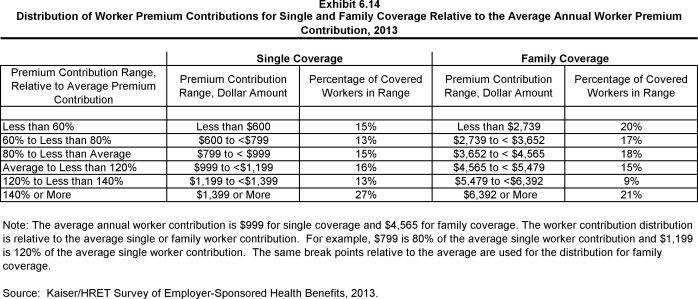

- There is a great deal of variation in worker contributions to premiums.

- Twenty-seven percent of covered workers contribute $1,399 or more annually (140% or more of the average worker contribution) for single coverage, while 15% of covered workers have an annual worker contribution of less than $600 (less than 60% of the average worker contribution) (Exhibit 6.14).

- For family coverage, 21% of covered workers contribute $6,392 or more annually (140% or more of the average worker contribution), while 20% of covered workers have an annual worker contribution of less than $2,739 (less than 60% of the average worker contribution) (Exhibit 6.14).

- The majority of covered workers are employed by a firm that contributes at least half of the premium for single and family coverage.

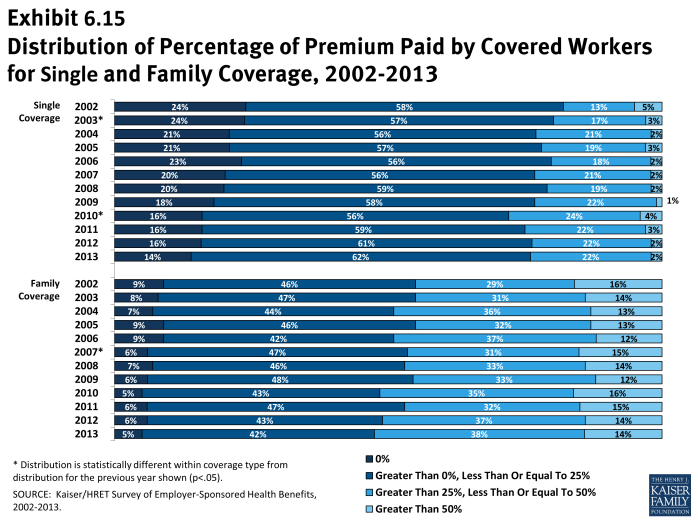

- Fourteen percent of covered workers with single coverage and 5% of covered workers with family coverage work for a firm that pays 100% of the premium (Exhibit 6.15).

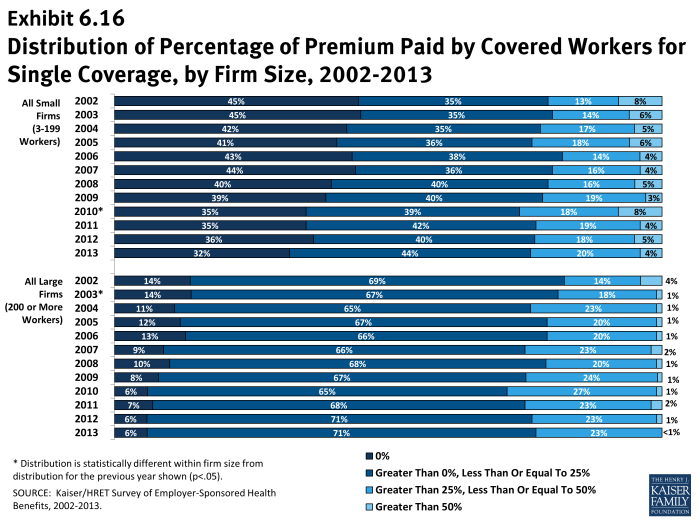

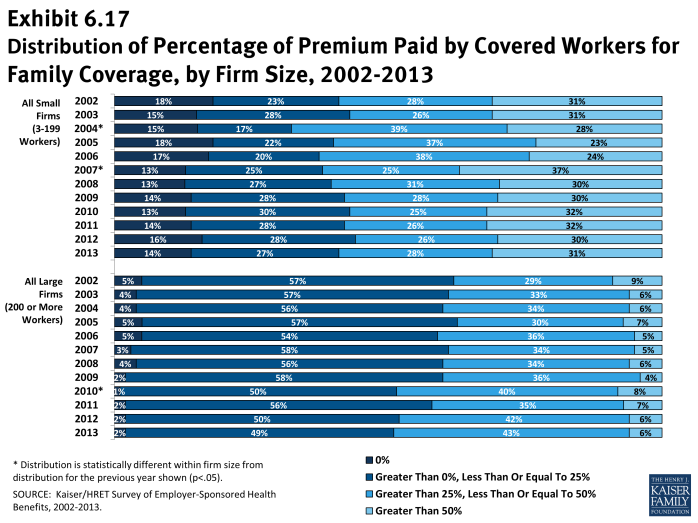

- Covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) are more likely to work for a firm that pays 100% of the premium for single coverage than workers in large firms (200 or more workers). Thirty-two percent of covered workers in small firms have an employer that pays the full premium for single coverage, compared to 6% of covered workers in large firms (Exhibit 6.16). For family coverage, 14% percent of covered workers in small firms have an employer that pays the full premium, compared to 2% of covered workers in large firms (Exhibit 6.17).

- Four percent of covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) contribute more than 50% of the premium for single coverage, compared to less than one percent of covered workers in large firms (200 or more workers) (Exhibit 6.16). For family coverage, 31% of covered workers in small firms work in a firm where they must contribute more than 50% of the premium, compared to 6% of covered workers in large firms (Exhibit 6.17).

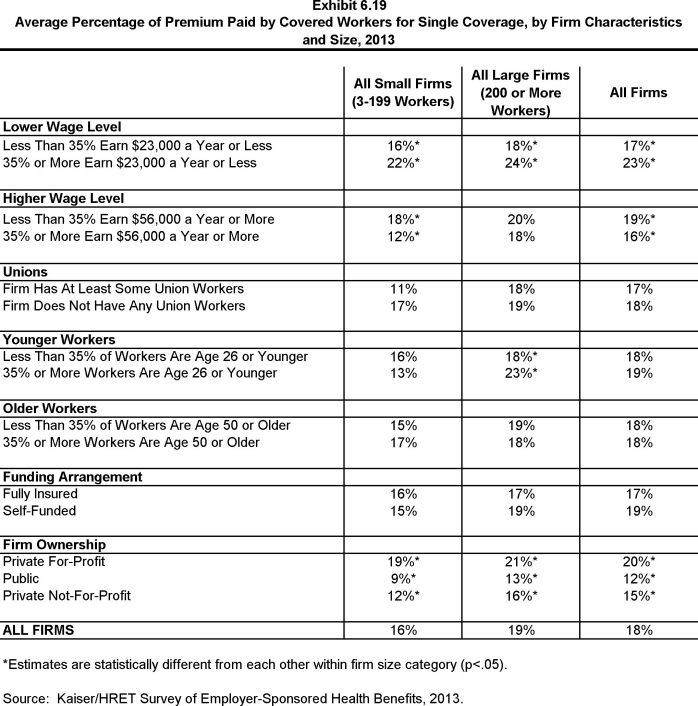

- The percentage of the premium paid by covered workers varies by several firm characteristics.

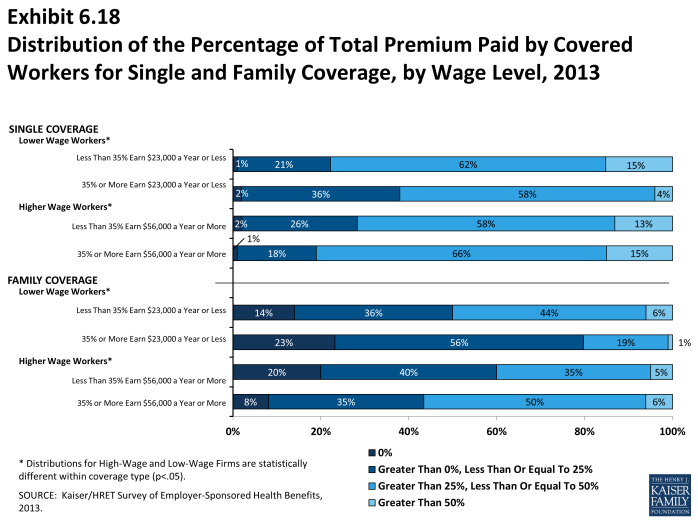

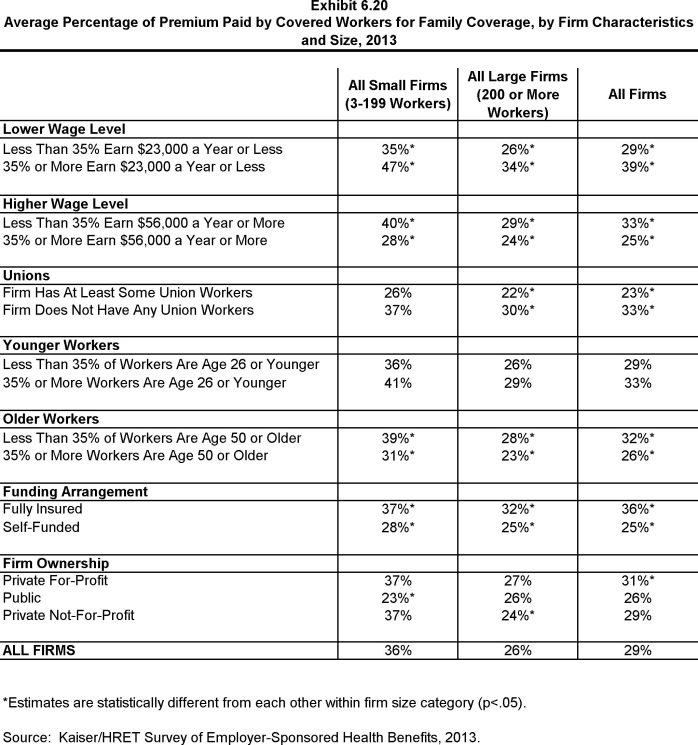

- For family coverage, covered workers in firms with many lower-wage workers (35% or more earn $23,000 or less annually) contribute a greater percentage of the premium than those in firms with fewer lower-wage workers (39% vs. 29%).

- Covered workers with family coverage in firms that have at least some union workers contribute a significantly lower percentage of the premium than those in firms without any unionized workers (23% vs. 33%) (Exhibit 6.20).

- For workers with family coverage in large firms (200 or more workers), the average percentage contribution for workers in firms that are partially or completely self-funded is lower than the average percentage contributions for workers in firms that are fully insured (25% vs. 32%)2 (Exhibit 6.20).

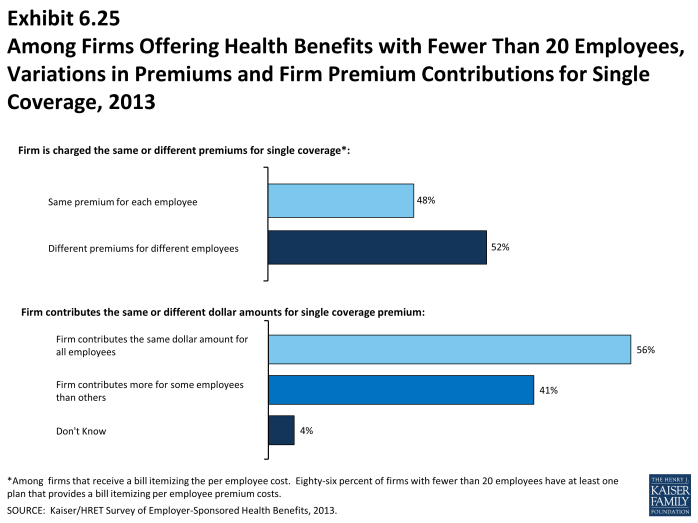

- Among firms offering health benefits with fewer than 20 employees, 41% contribute different dollar amounts toward premiums for different employees (Exhibit 6.25). Employer may contribute different amounts to different employees based for a variety of reasons, including workers’ age, smoking status, seniority, job title or location.

Changes over Time

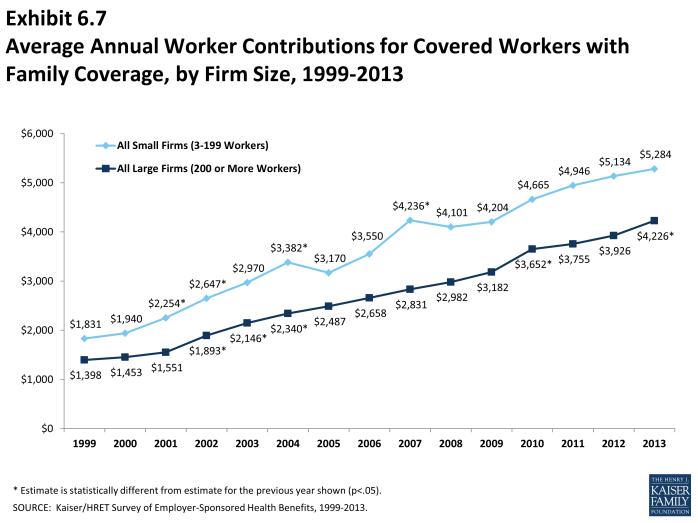

- The amount which workers contribute to single coverage premiums has increased 97 percent since 2003 and 39% since 2008. Covered workers’ contributions to family coverage have increased 89% since 2003 and 36% since 2008.

Section Six: Worker and Employer Contributions for Premiums

exhibits

Average Monthly Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, 1999-2013

Average Annual Worker and Employer Contributions to Premiums and Total Premiums for Single Coverage, 1999-2013

Average Annual Worker and Employer Contributions to Premiums and Total Premiums for Family Coverage, 1999-2013

Average Annual Firm and Worker Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 2013

Average Annual Worker Contributions for Covered Workers with Single Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2013

Average Annual Worker Contributions for Covered Workers with Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2013

Average Annual Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2013

Average Annual Firm and Worker Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Covered Workers for Single Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013

Average Annual Firm and Worker Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Covered Workers for Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013

Average Monthly and Annual Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013

Average Monthly and Annual Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Region, 2013

Average Monthly Worker Premium Contributions Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 1999-2013

Distribution of Worker Premium Contributions for Single and Family Coverage Relative to the Average Annual Worker Premium Contribution, 2013

Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, 2002-2013

Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single Coverage, by Firm Size, 2002-2013

Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 2002-2013

Distribution of the Percentage of Total Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Wage Level, 2013

Average Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single Coverage, by Firm Characteristics and Size, 2013

Average Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Family Coverage, by Firm Characteristics and Size, 2013

Average Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013

Average Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 1999-2013

Average Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Region, 2013

Section Seven: Employee Cost Sharing

In addition to any required premium contributions, most covered workers face cost sharing for the medical services they use. Cost sharing for medical services can take a variety of forms, including deductibles (an amount that must be paid before some or all services are covered by the plan), copayments (fixed dollar amounts), and/or coinsurance (a percentage of the charge for services). The type and level of cost sharing often vary by the type of plan in which the worker is enrolled. Cost sharing may also vary by the type of service, such as office visits, hospitalizations, or prescription drugs.

The cost-sharing amounts reported here are for covered workers using services provided in-network by participating providers. Plan enrollees receiving services from providers that do not participate in plan networks often face higher cost sharing and may be responsible for charges that exceed plan allowable amounts. The framework of this survey does not allow us to capture all of the complex cost-sharing requirements in modern plans, particularly for ancillary services (such as durable medical equipment or physical therapy) or cost-sharing arrangements that vary across different settings (such as tiered networks). Therefore, we do not collect information on all plan provisions and limits that affect enrollee out-of-pocket liability.

General Annual Deductibles

- A general annual deductible is an amount that must be paid by the enrollee before most services are covered by their health plan. Some plans require enrollees to meet a service specific deductible such as on prescription drugs or hospital admissions in lieu of or in addition to a general deductible. Federal law requires that some services such as preventative care are covered by some plans without cost sharing.

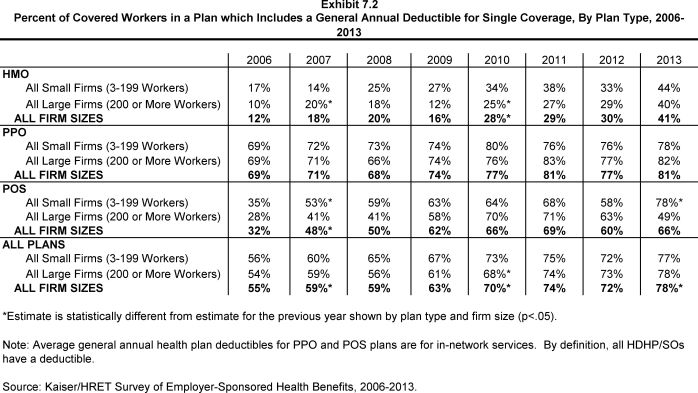

- Seventy-eight percent of covered workers are enrolled in a plan with a general annual deductible for single coverage. More covered workers are enrolled in a plan with a general annual deductible in 2013 than in 2012 (78% vs. 72%) (Exhibit 7.2). Since 2006, the percent of covered workers with a general annual deductible has increased from 55% to 78%.

- The percent of covered workers enrolled in a plan with a general annual deductible is similar for small (3-199 workers) and larger firms (77% and 78%) (Exhibit 7.2).

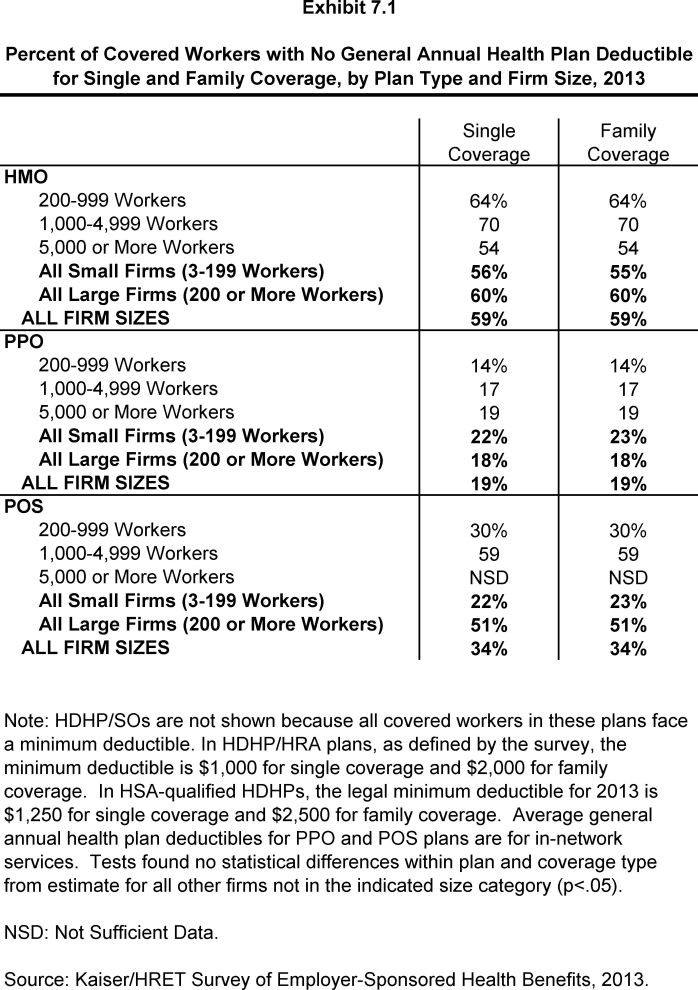

- The likelihood of having a deductible varies by plan type. Workers in HMOs are less likely to have a general annual deductible for single coverage compared to workers in other plan types. Fifty-nine percent of workers in HMOs do not have a general annual deductible, compared to 34% of workers in POS plans and 19% of workers in PPOs (Exhibit 7.1).

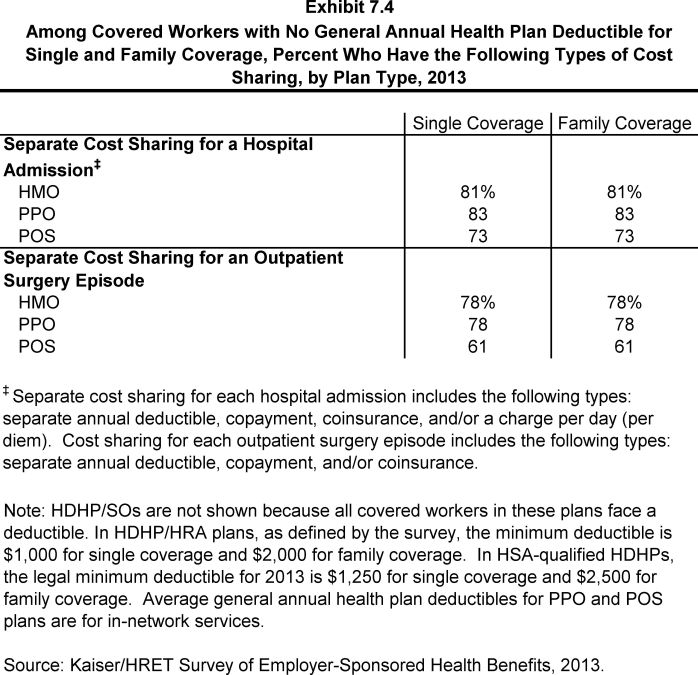

- Workers without a general annual plan deductible often have other forms of cost sharing for medical services. For workers without a general annual deductible for single coverage, 81% in HMOs, 83% in PPOs, and 73% in POS plans are in plans that require cost sharing for hospital admissions. The percentages are similar for family coverage (Exhibit 7.4).

- The dollars amounts of general annual deductibles vary greatly by plan type and firm size.

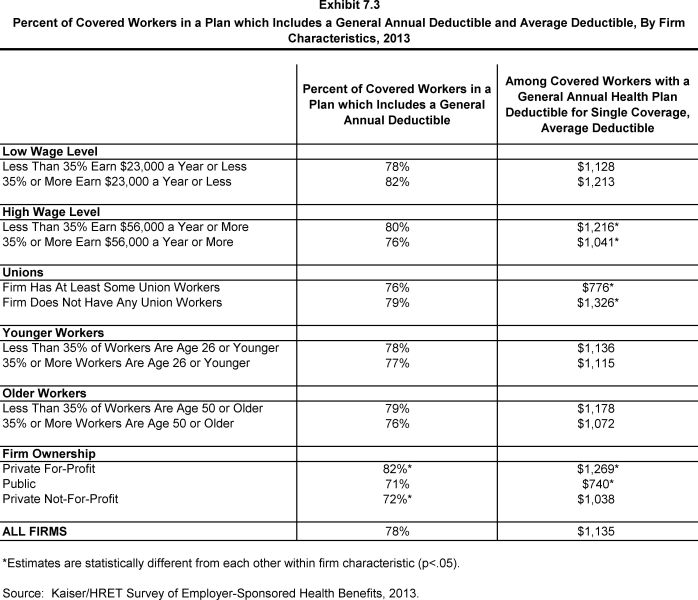

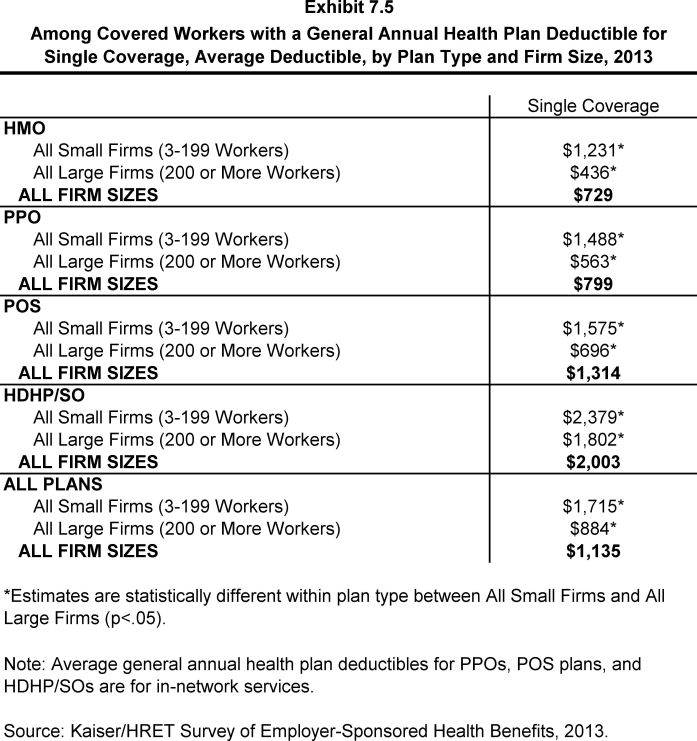

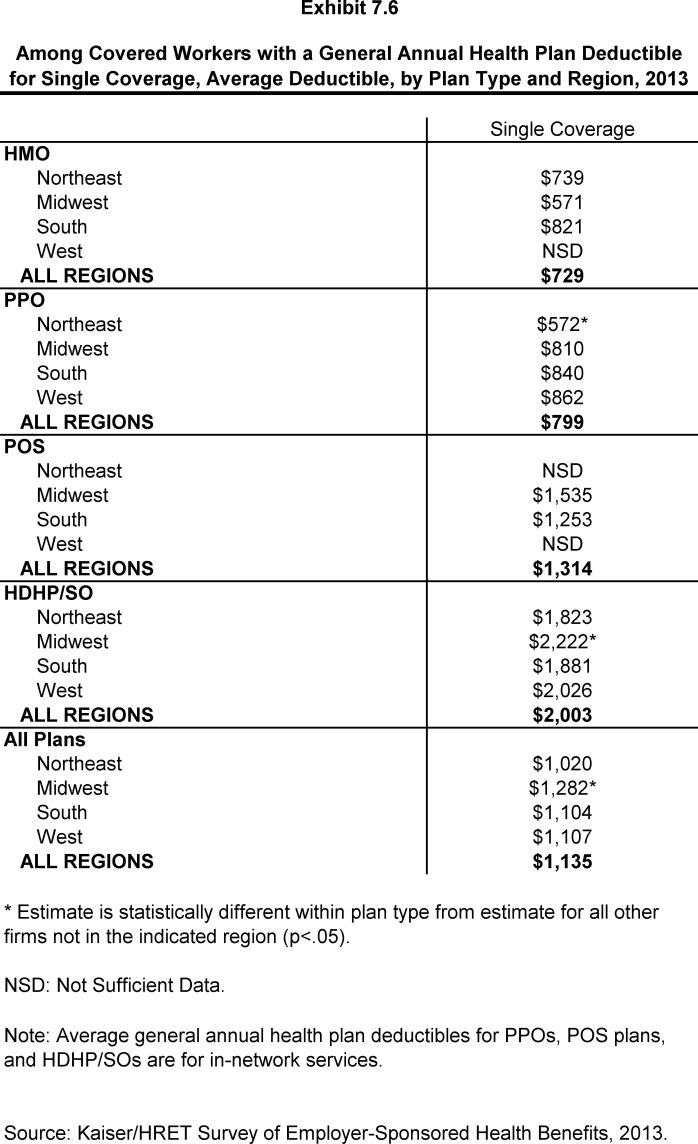

- The average annual deductible is $1,135. There are differences in the average general annual deductible by plan type. The average annual deductibles among those covered workers with a deductible for single coverage are $729 for HMOs, $799 for PPOs, $1,314 for POS plans, and $2,003 for HDHP/SOs (Exhibit 7.5). Overall, the average general annual deductible for all covered workers is $1,135.

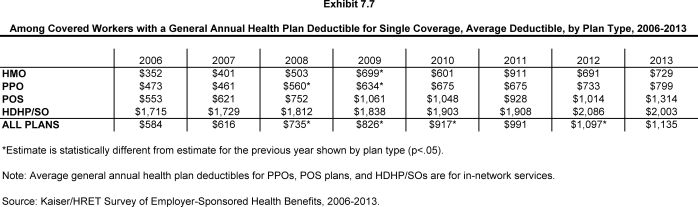

- There is no statistically significant change in deductible amounts from 2012 to 2013 for any plan type (Exhibit 7.7).

- Deductibles are generally higher for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) than for covered workers in large firms (200 or more workers) across plan types (Exhibit 7.5). For covered workers in PPOs, deductibles in small firms are more than twice as large as deductibles in large firms ($1,488 vs. $563). On average, covered workers at small firms face higher general annual deductibles than covered workers at large firms ($1,715 vs. $884) (Exhibit 7.5).

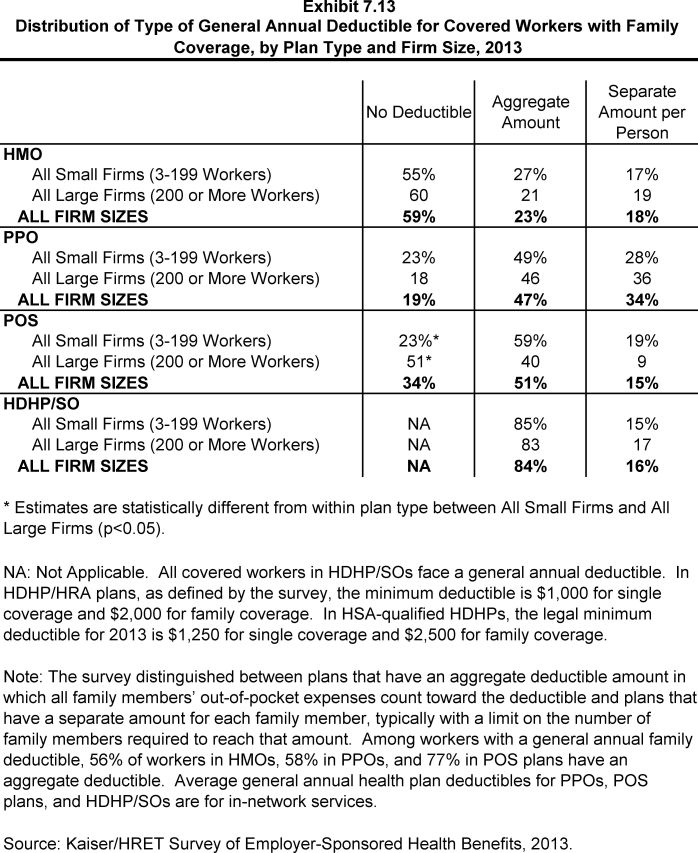

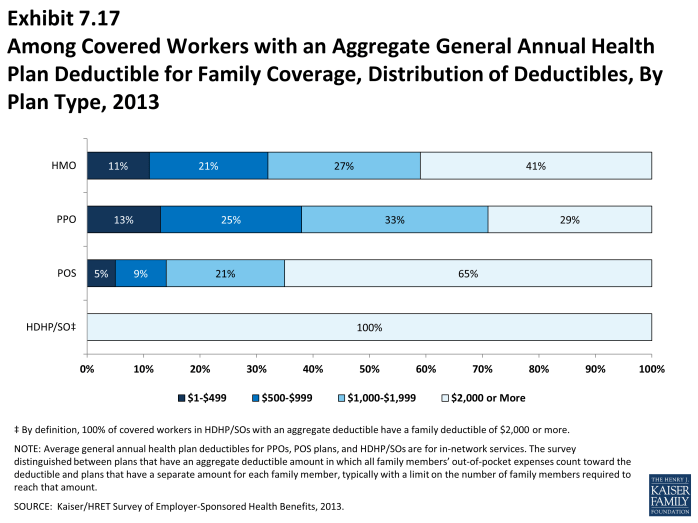

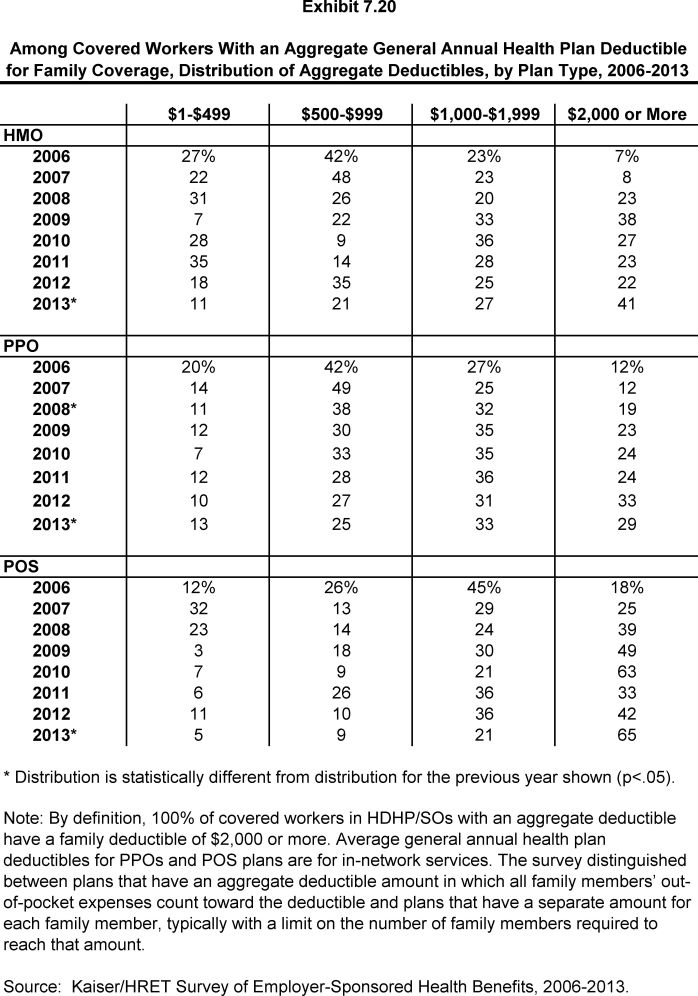

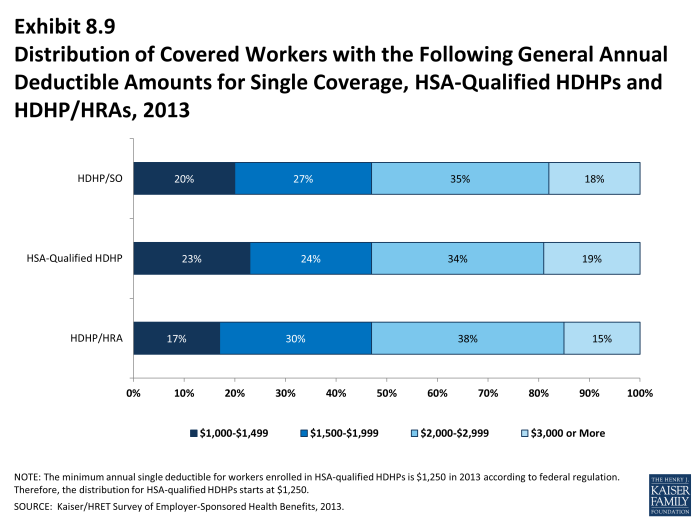

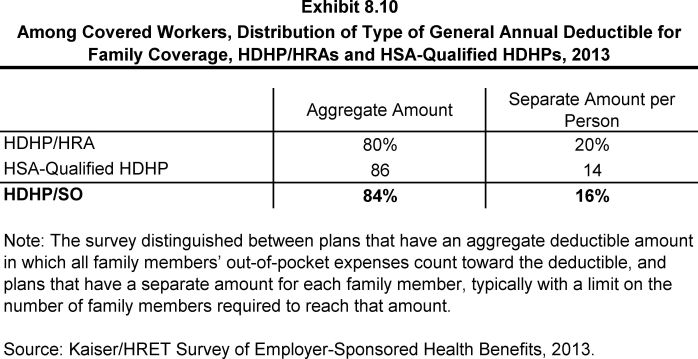

- For family coverage, the majority of workers with general annual deductibles have an aggregate deductible, meaning all family members’ out-of-pocket expenses count toward meeting the deductible amount. Among those with a general annual deductible for family coverage, the percentage of covered workers with an average aggregate general annual deductible is 56% for workers in HMOs, 58% for workers in PPOs, 77% for workers in POS plans and 84% for workers in HDHP/SOs (Exhibit 7.13).

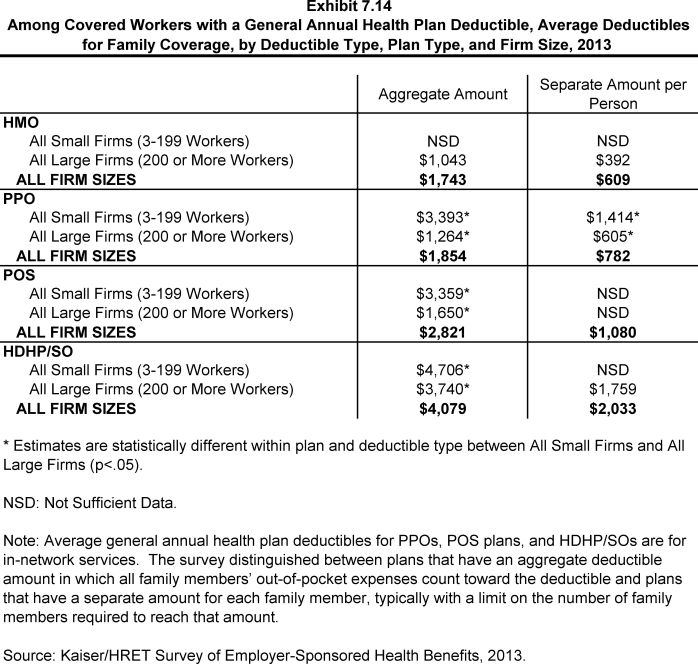

- The average amounts for workers with an aggregate deductible for family coverage are $1,743 for HMOs, $1,854 for PPOs, $2,821 for POS plans, and $4,079 for HDHP/SOs (Exhibit 7.14).

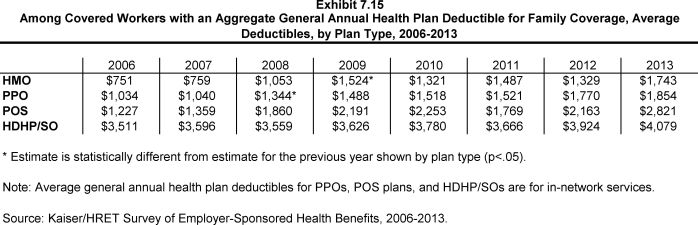

- The average aggregate deductible amounts for family coverage are similar to last year for each plan type (Exhibit 7.15).

- The other type of family deductible, a separate per-person deductible, requires each family member to meet a separate per-person deductible amount before the plan covers expenses for that member. Most plans with separate per-person family deductibles consider the deductible met for all family members if a prescribed number of family members each reach their separate deductible amounts. Plans may also require each family member to meet a separate per-person deductible until the family’s combined spending reaches a specified dollar amount.

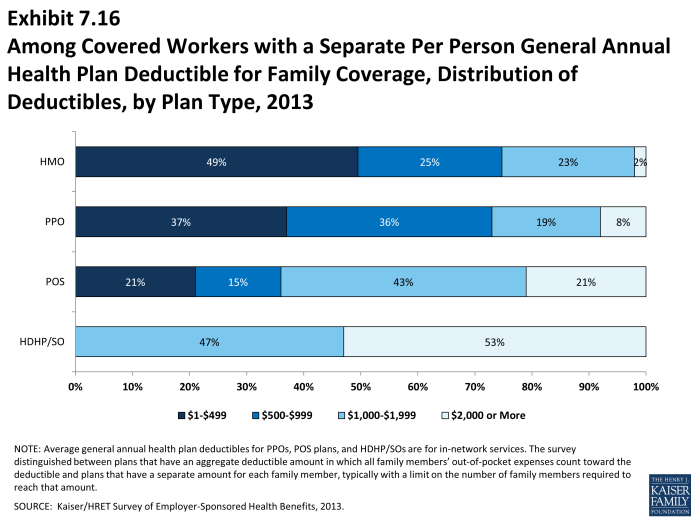

- For covered workers in health plans that have separate per-person general annual deductible amounts for family coverage, the average plan deductible amounts are $609 for HMOs, $782 for PPOs, $1,080 for POS plans, and $2,033 for HDHP/SOs (Exhibit 7.14).

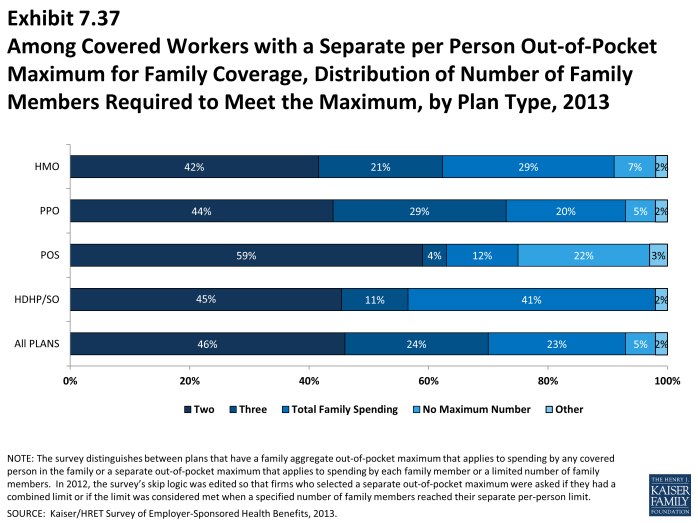

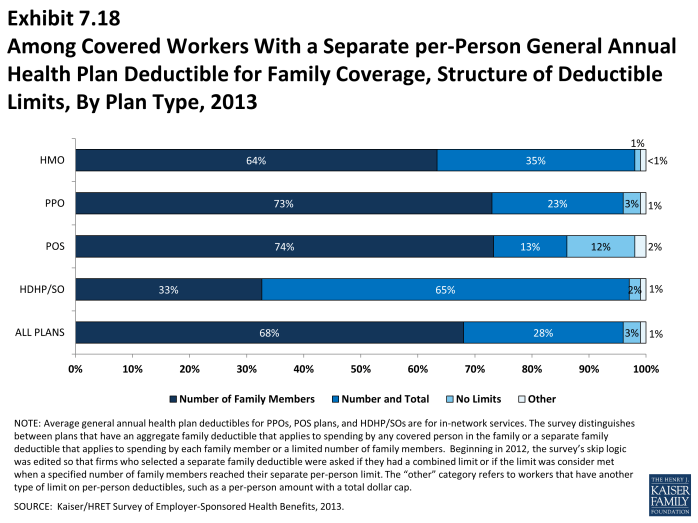

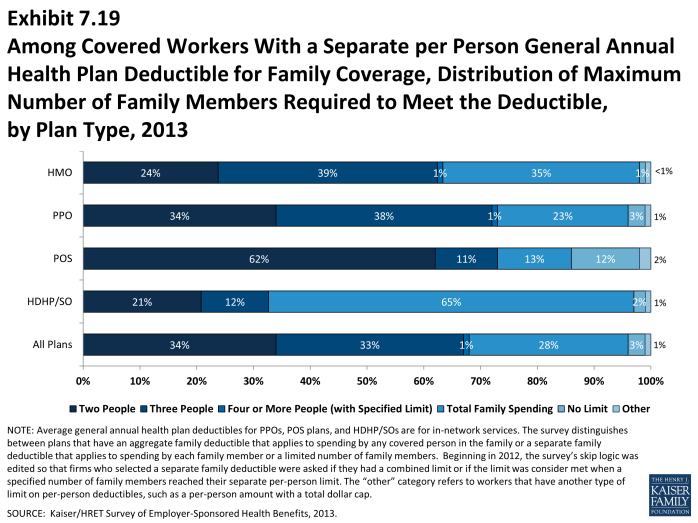

- Most covered workers in plans with a separate per-person general annual deductible for family coverage have a limit to the number of family members required to meet the separate deductible amounts (Exhibit 7.18).1 Among those workers in plans with a limit on the number of family members, the most frequent number of family members required to meet the separate deductible amounts is three for HMO and PPO plans, and two for POS plans (Exhibit 7.19).

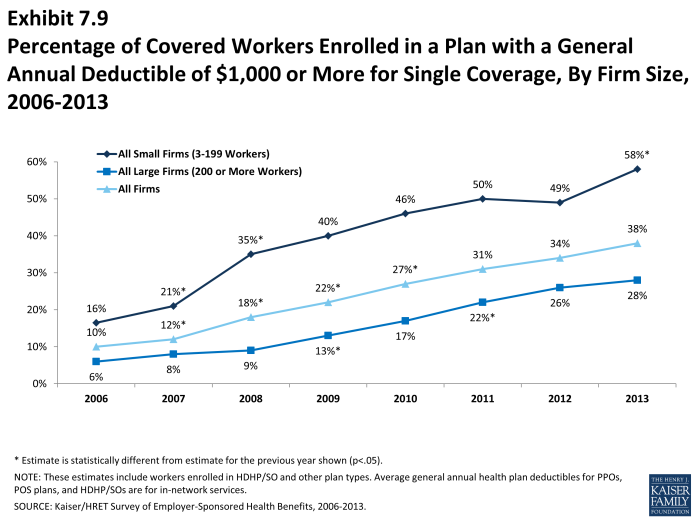

- Thirty-eight percent of covered workers are in plans with a deductible of $1000 or more for single coverage, similar to the percentage (34%) in 2012 (Exhibit 7.9).

- Over the last five years, the percentage of covered workers with a deductible of $1,000 or more for single coverage has increased from 18% to 38% (Exhibit 7.9). Workers in small firms (3-199 workers) are more likely to have a general annual deductible of $1,000 or more for single coverage than workers in large firms (200 or more workers) (58% vs. 28%) (Exhibit 7.8). The percent of covered workers at small firms (3-199 workers) who have a deductible of a $1,000 or more increased from 49% in 2012 to 58% in 2013 (Exhibit 7.9).

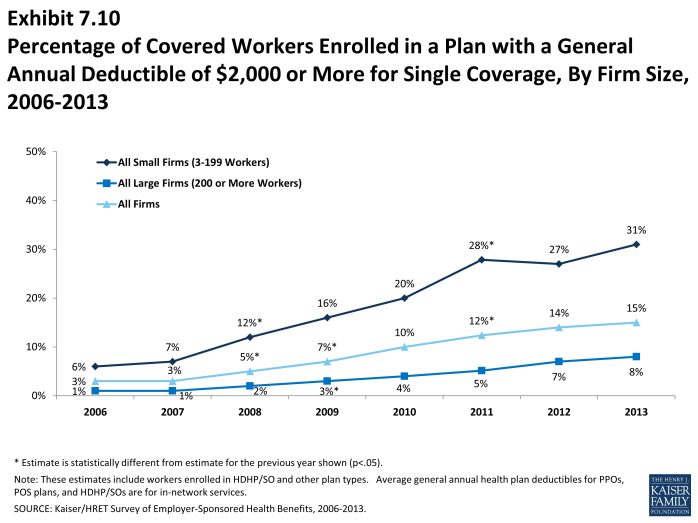

- Fifteen percent of covered workers are enrolled in a plan with a deductible of $2,000 or more. Thirty-one percent of covered workers at small firms (3-199 workers) have a general annual deductible of $2,000 or more (Exhibit 7.8).

- The majority of covered workers with a deductible are in plans where the deductible does not have to be met before certain services, such as physician office visits or prescription drugs, are covered.

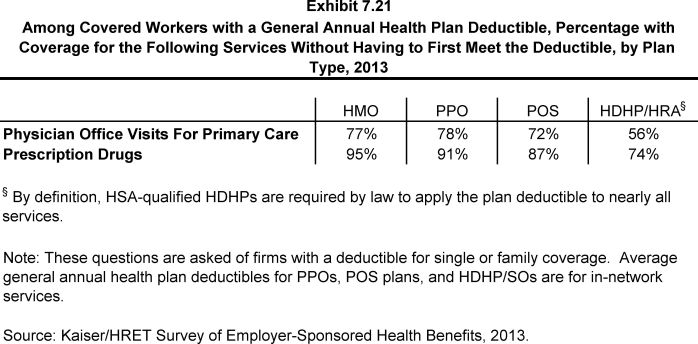

- Large majorities of covered workers (77% in HMOs, 78% in PPOs, and 72% in POS plans) with general plan deductibles are enrolled in plans where the deductible does not have to be met before physician office visits for primary care are covered (Exhibit 7.21).

- Similarly, among workers with a general annual deductible, large shares of covered workers in HMOs (95%), PPOs (91%), and POS plans (87%) are enrolled in plans where the general annual deductible does not have to be met before prescription drugs are covered (Exhibit 7.21).

Hospital and Outpatient Surgery Cost Sharing

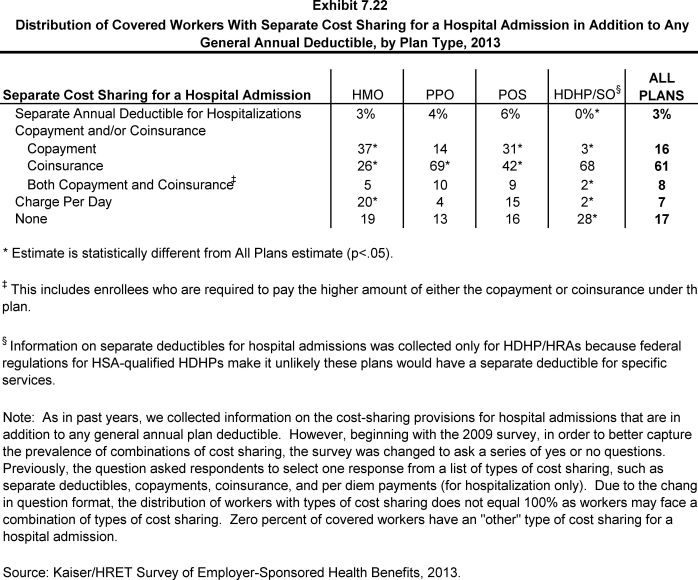

- In order to better capture the prevalence of combinations of cost sharing for inpatient hospital stays and outpatient surgery, the survey was changed to ask a series of yes or no questions beginning in 2009. The new format allowed respondents to indicate more than one type of cost sharing for these services, if applicable. Previously, the questions asked respondents to select just one response from a list of types of cost sharing, such as separate deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, and per diem payments (for hospitalization only). Due to the change in question format, the distribution of workers with types of cost sharing does not equal 100% as workers may face a combination of types of cost sharing. In addition, the average copayment and coinsurance rates for hospital admissions include workers who may have a combination of these types of cost sharing.

- Whether or not a worker has a general annual deductible, most workers face additional types of cost sharing when admitted to a hospital or having outpatient surgery (such as a copayment, coinsurance, or a per diem charge).

- For hospital admissions, 61% of covered workers have coinsurance and 16% have copayments. Lower percentages of workers have per day (per diem) payments (7%), a separate hospital deductible (3%), or both copayments and coinsurance (8%), while 17% have no additional cost sharing for hospital admissions after any general annual deductible has been met (Exhibit 7.22). For covered workers in HMO plans, copayments are more common (37%) and coinsurance (26%) is less common than in other plan types.

- The percent of covered workers in a plan which requires coinsurance for hospital admission has increased from 53% in 2010 to 61% in 2013.

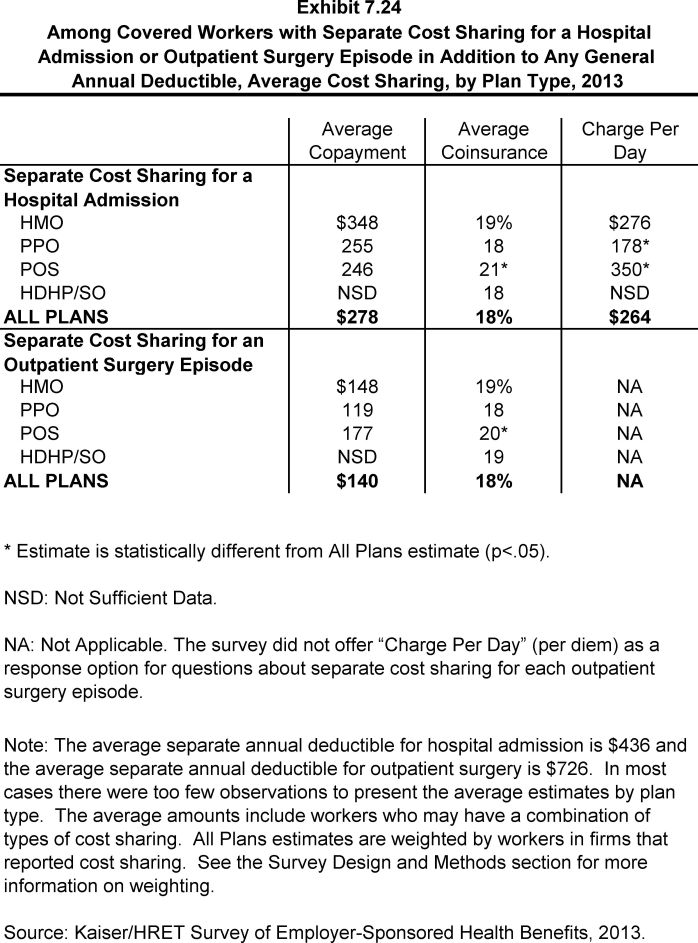

- The average coinsurance rate is 18%; the average copayment is $278 per hospital admission; the average per diem charge is $264; and the average separate annual hospital deductible is $436 (Exhibit 7.24).

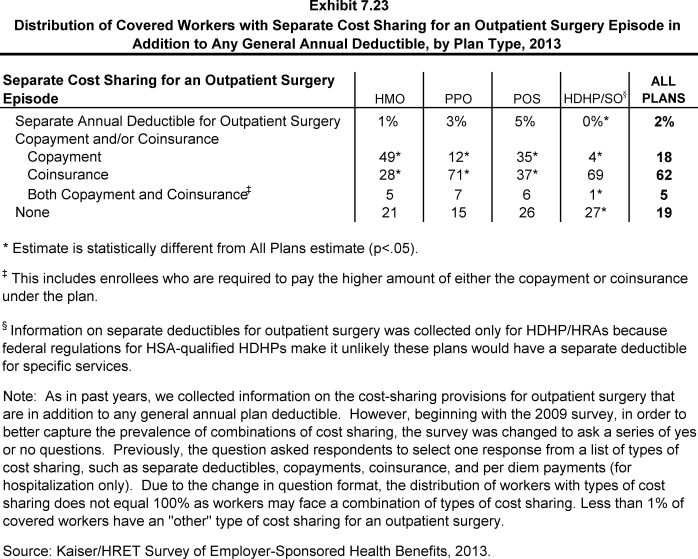

- The cost-sharing provisions for outpatient surgery are similar to those for hospital admissions, as most workers have coinsurance or copayments. Sixty-two percent of covered workers have coinsurance and 18% have copayments for an outpatient surgery episode. In addition, 2% have a separate annual deductible for outpatient surgery, and 5% have both copayments and coinsurance, while 19% have no additional cost sharing after any general annual deductible has been met (Exhibit 7.23).

- For covered workers with cost sharing, the average coinsurance is 18%, the average copayment is $140, and the average separate annual outpatient surgery deductible is $726 (Exhibit 7.24).

Cost Sharing for Physician Office Visits

- The majority of covered workers are enrolled in health plans that require cost sharing for an in-network physician office visit, in addition to any general annual deductible.2

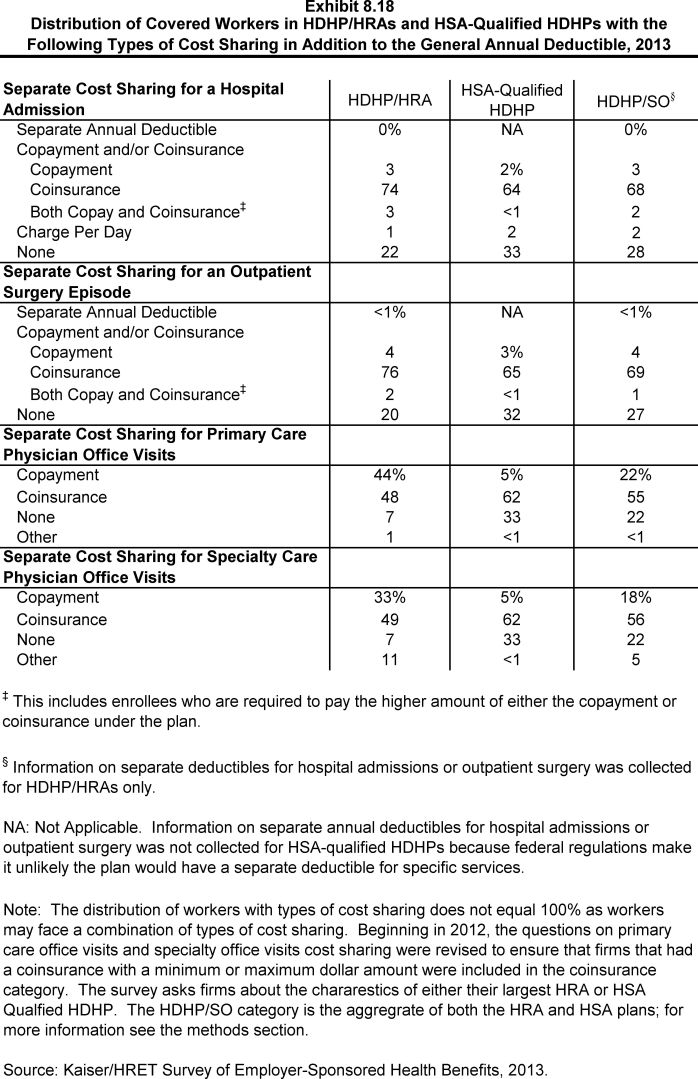

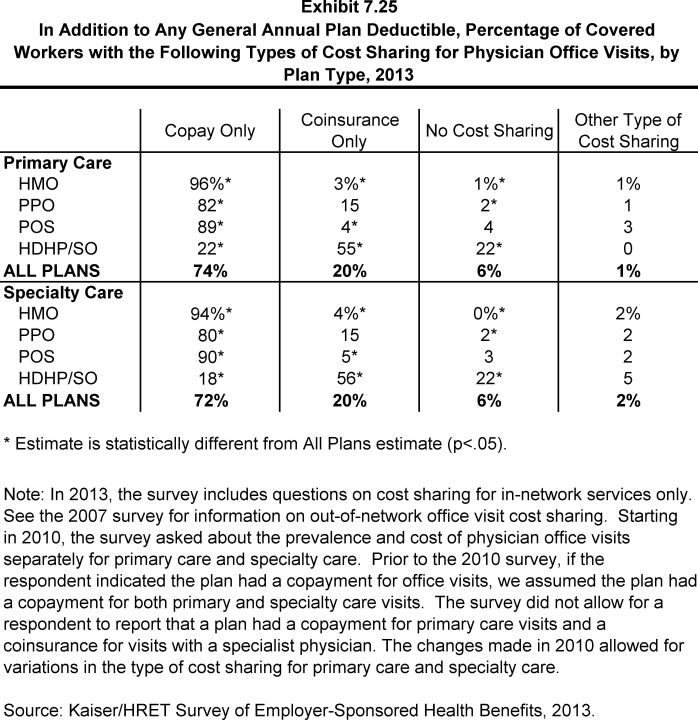

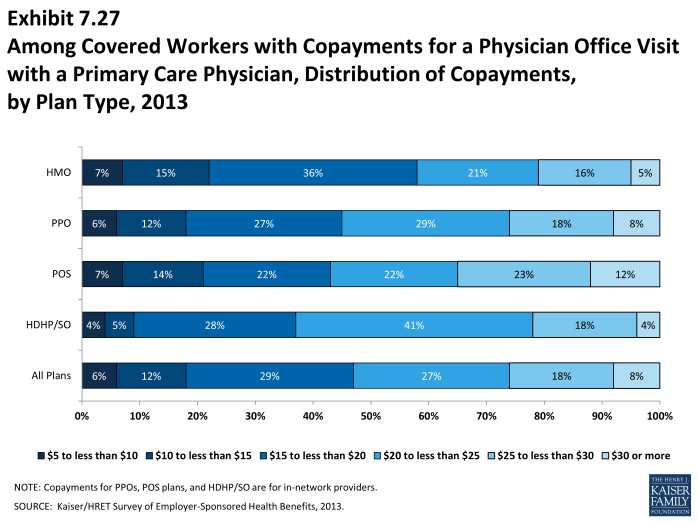

- The most common form of physician office visit cost sharing for in-network services is copayments. Seventy-four percent of covered workers have a copayment for a primary care physician office visit and 20% have coinsurance. For office visits with a specialty physician, 72% of covered workers have copayments and 20% have coinsurance. Workers in HMOs, PPOs, and POS plans are much more likely to have copayments than workers in HDHP/SOs for both primary care and specialty care physician office visits. For example, the majority of workers in HDHP/SOs have coinsurance (55%) or no cost sharing after the general annual plan deductible is met (22%) for primary care physician office visits (Exhibit 7.25).

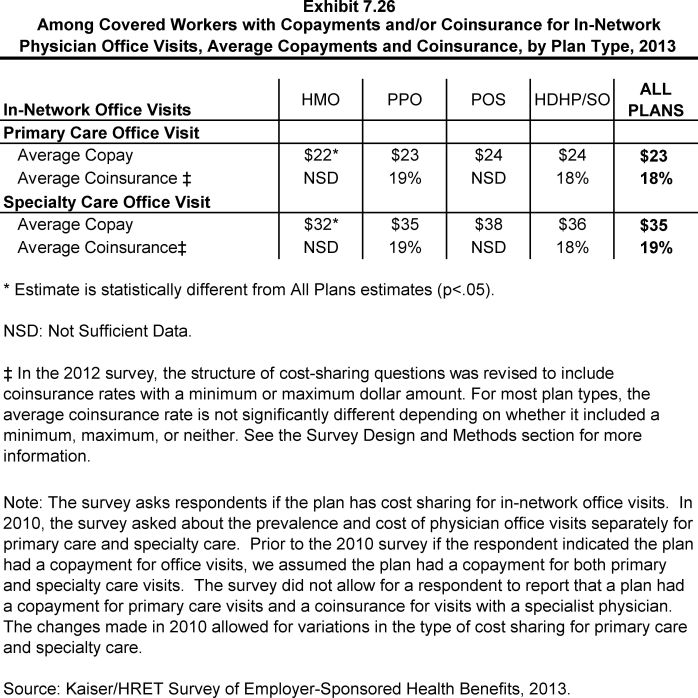

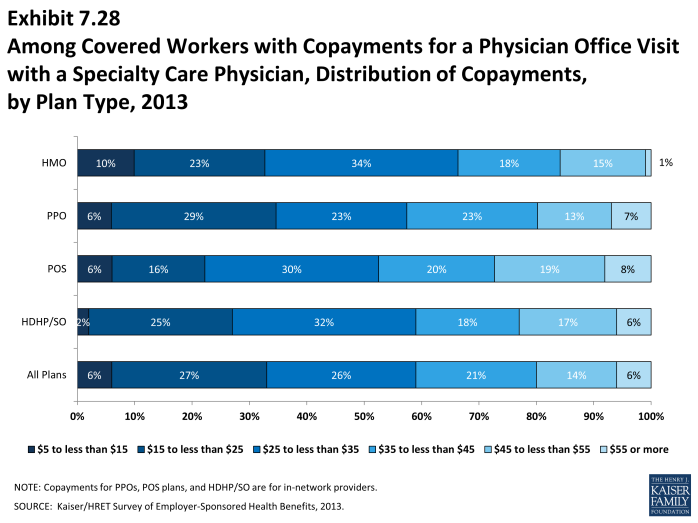

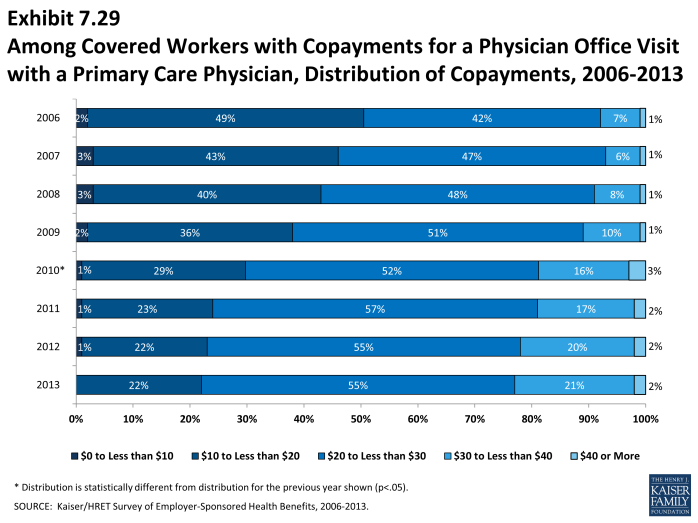

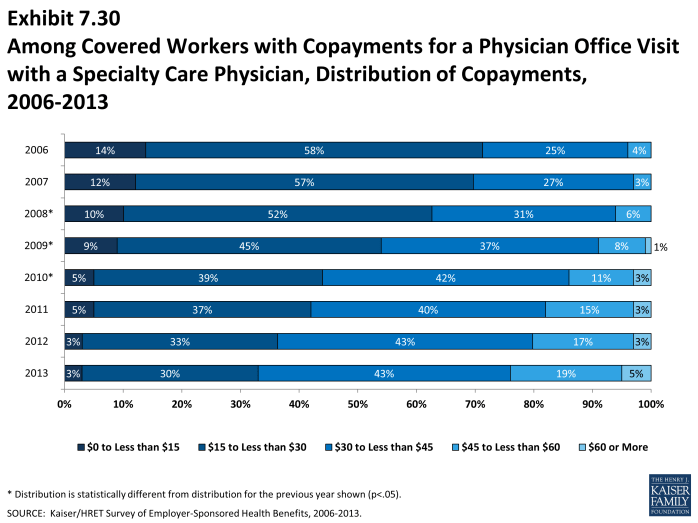

- Among covered workers with a copayment for in-network physician office visits, the average copayment is $23 for primary care and $35 for specialty physicians (Exhibit 7.26), similar to $23 and $33 reported in 2012.

- Among workers with coinsurance for in-network physician office visits, the average coinsurance rates are 18% for a visit with a primary care physician and 19% for a visit with a specialist (Exhibit 7.26).

Out-Of-Pocket Maximum Amounts

- Most covered workers are in a plan that partially or totally limits the cost sharing that a plan enrollee must pay in a year. These limits are generally referred to as out-of-pocket maximum amounts. Enrollee cost sharing, such as deductibles, office visit cost sharing, or spending on prescription drugs, may or may not apply to the out-of-pocket maximum. Therefore, the survey asks what types of out-of-pocket expenses count when determining whether a covered worker has met the plan out-of-pocket maximum. When a plan does not count certain types of spending, it effectively increases the amount a worker may pay out-of-pocket.

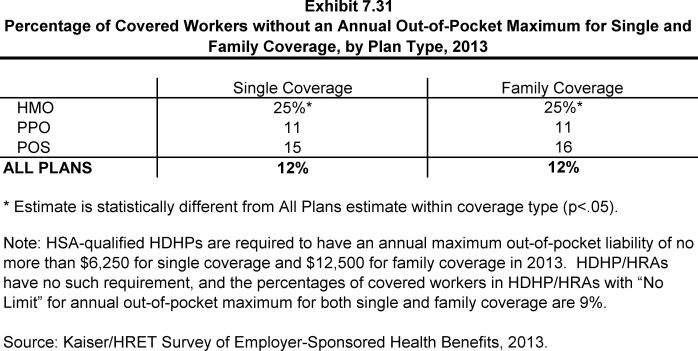

- Twelve percent of covered workers are in a plan that does not limit the amount of cost sharing enrollees have to pay for either single or family coverage (Exhibit 7.31).

- Covered workers with single or family coverage in HMOs (25%) are more likely to be enrolled in a plan that does not limit the amount of cost sharing than workers in PPOs (11%) (Exhibit 7.31).

- Covered workers without an out-of-pocket maximum, however, may not have large cost-sharing responsibilities. For example, 76% of covered workers in HMOs with no out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage have no general annual deductible, only 2% have coinsurance for a hospital admission and less than 1% have coinsurance for outpatient surgery episodes.

- HSA-qualified HDHPs are required by law to have an out-of-pocket maximum of no more than $6,250 for single coverage and $12,500 for family coverage in 2013. HDHP/HRAs have no such requirement, and among workers enrolled in these plans, 9% have no out-of-pocket maximum for single or family coverage.

- For covered workers with out-of-pocket maximums, there is wide variation in spending limits.

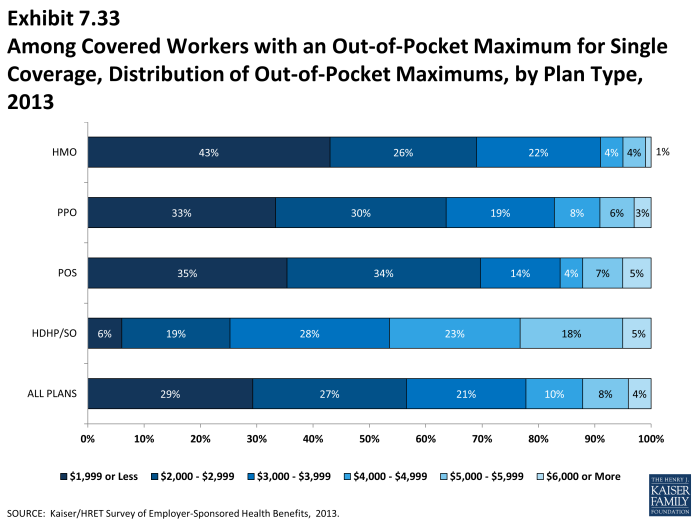

- Twenty-nine percent of covered workers with an out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage have an out-of-pocket maximum of less than $2,000, while 12% have an out-of-pocket maximum of $5,000 or more (Exhibit 7.33). Covered workers with an out-of-pocket maximum in small firms (3 to 199 workers) are more likely than such workers in larger firms to be covered by a plan with an out-of-pocket maximum of $3,000 or more (52% vs. 39%).

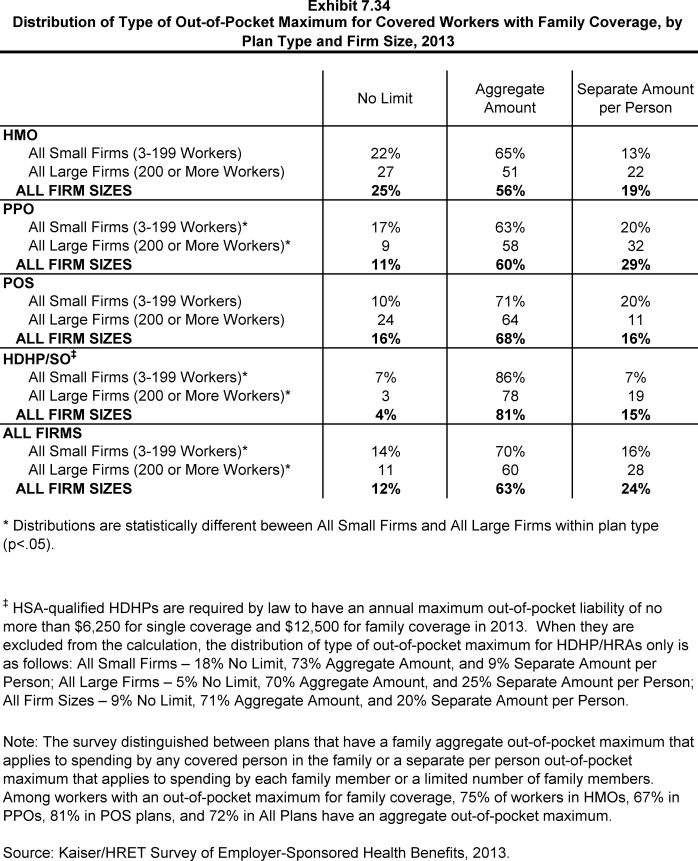

- Like deductibles, some plans have an aggregate out-of-pocket maximum amount for family coverage that applies to cost sharing for all family members, while others have a per-person out-of-pocket maximum that limits the amount of cost sharing that the family must pay on behalf of each family member. Sixty-three percent of covered workers in a plan with an out-of-pocket maximum are in a plan with an aggregate limit (Exhibit 7.34).

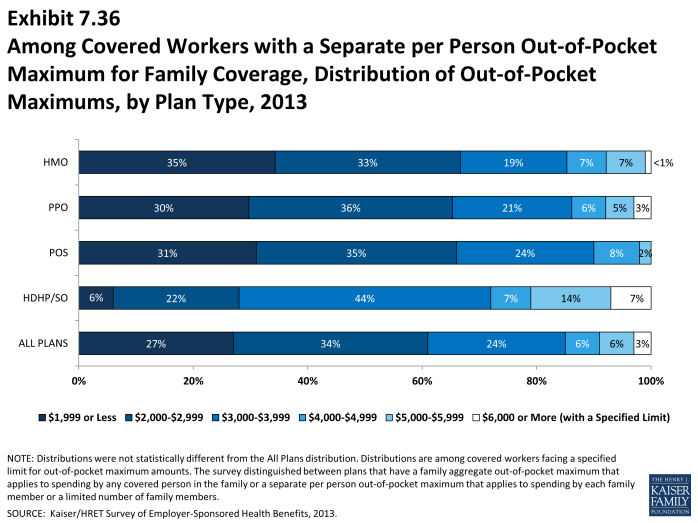

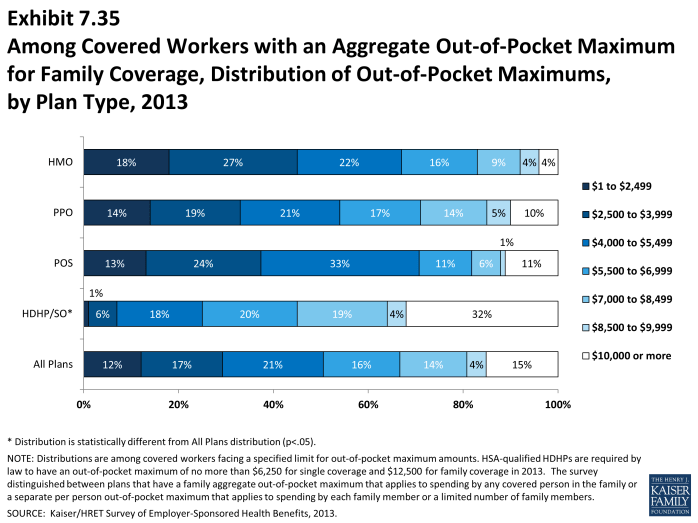

- For covered workers with an aggregate out-of-pocket maximum for family coverage, 29% have an out-of-pocket maximum of less than $4,000 and 24% have an out-of-pocket maximum of $8,000 or more (Exhibit 7.35). Among workers with separate per-person out-of-pocket limits for family coverage, 85% have out-of-pocket maximums of less than $4,000 (Exhibit 7.36).

- As noted above, covered workers with an out-of-pocket maximum may be enrolled in a plan where not all spending counts toward the out-of-pocket maximum, potentially exposing workers to higher out-of-pocket spending.

- Among workers enrolled in PPO plans with an out-of-pocket maximum for single or family coverage, 34% are in plans that do not count spending for the general annual plan deductible toward the out-of-pocket limit (Exhibit 7.32).

- It is more common for covered workers to be in plans that do not count prescription drug cost sharing toward the out-of-pocket limit. Eighty-four percent of workers enrolled in PPO plans and 71% enrolled in HMO plans with an out-of-pocket maximum for single or family coverage are in plans that do not count prescription drug spending towards the out-of-pocket maximum (Exhibit 7.32). The ACA will require that all non-grandfathered plans have an out-of-pocket maximum that counts all cost sharing towards the limit.

Section Seven: Employee Cost Sharing

exhibits

Percent of Covered Workers with No General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013

Percent of Covered Workers in a Plan which Includes a General Annual Deductible for Single Coverage, By Plan Type, 2006-2013

Percent of Covered Workers in a Plan which Includes a General Annual Deductible and Average Deductible, By Firm Characteristics, 2013

Among Covered Workers with No General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Single and Family Coverage, Percent Who Have the Following Types of Cost Sharing, by Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers with a General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Single Coverage, Average Deductible, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013

Among Covered Workers with a General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Single Coverage, Average Deductible, by Plan Type and Region, 2013

Among Covered Workers with a General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Single Coverage, Average Deductible, by Plan Type, 2006-2013

Percentage of Covered Workers Enrolled in a Plan with a High General Annual Deductible for Single Coverage, By Firm Size, 2013

Percentage of Covered Workers Enrolled in a Plan with a General Annual Deductible of $1,000 or More for Single Coverage, By Firm Size, 2006-2013

Percentage of Covered Workers Enrolled in a Plan with a General Annual Deductible of $2,000 or More for Single Coverage, By Firm Size, 2006-2013

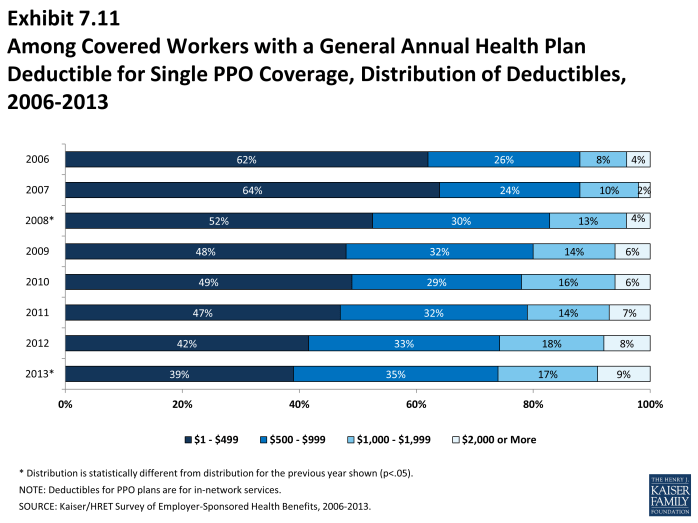

Among Covered Workers with a General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Single PPO Coverage, Distribution of Deductibles, 2006-2013

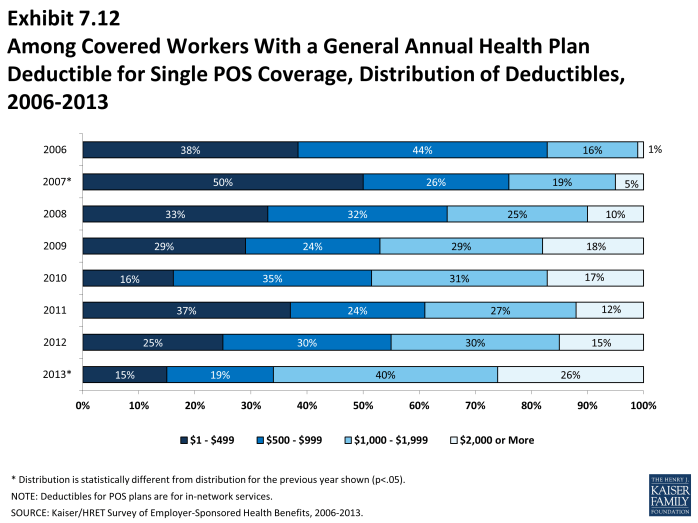

Among Covered Workers With a General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Single POS Coverage, Distribution of Deductibles, 2006-2013

Distribution of Type of General Annual Deductible for Covered Workers with Family Coverage, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013

Among Covered Workers with a General Annual Health Plan Deductible, Average Deductibles for Family Coverage, by Deductible Type, Plan Type, and Firm Size, 2013

Among Covered Workers with an Aggregate General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Family Coverage, Average Deductibles, by Plan Type, 2006-2013

Among Covered Workers with a Separate Per Person General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Family Coverage, Distribution of Deductibles, by Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers with an Aggregate General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Family Coverage, Distribution of Deductibles, By Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers With a Separate Per Person General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Family Coverage, Structure of Deductible Limits, By Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers With a Separate Per Person General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Family Coverage, Distribution of Maximum Number of Family Members Required to Meet the Deductible, by Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers With an Aggregate General Annual Health Plan Deductible for Family Coverage, Distribution of Aggregate Deductibles, by Plan Type, 2006-2013

Among Covered Workers with a General Annual Health Plan Deductible, Percentage with Coverage for the Following Services Without Having to First Meet the Deductible, by Plan Type, 2013

Distribution of Covered Workers With Separate Cost Sharing for a Hospital Admission in Addition to Any General Annual Deductible, by Plan Type, 2013

Distribution of Covered Workers with Separate Cost Sharing for an Outpatient Surgery Episode in Addition to Any General Annual Deductible, by Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers with Separate Cost Sharing for a Hospital Admission or Outpatient Surgery Episode in Addition to Any General Annual Deductible, Average Cost Sharing, by Plan Type, 2013

In Addition to Any General Annual Plan Deductible, Percentage of Covered Workers with the Following Types of Cost Sharing for Physician Office Visits, by Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers with Copayments and/or Coinsurance for In-Network Physician Office Visits, Average Copayments and Coinsurance, by Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers with Copayments for a Physician Office Visit with a Primary Care Physician, Distribution of Copayments, by Plan Type, 2013

Among Covered Workers with Copayments for a Physician Office Visit with a Specialty Care Physician, Distribution of Copayments, by Plan Type, 2013