An Early Look at Medicaid Expansion Waiver Implementation in Michigan and Indiana

What are the Implications for Coverage and Access under Michigan and Indiana’s Waivers?

Like other states that have expanded Medicaid, Michigan and Indiana experienced reductions in the number of uninsured residents and large gains in Medicaid enrollment. Between 2013 and 2015, the uninsured rate fell by 7.7 percentage points in Michigan, and 7.2 percentage points in Indiana, both larger than the national average decrease of 6.1 percentage points and the 6.7 percentage point decrease in all Medicaid expansion states.1 Along with reductions in the uninsured, Michigan and Indiana both experienced large increases in Medicaid enrollment, as expected by the coverage expansion. There are over 650,000 beneficiaries enrolled in Healthy Michigan as of December 2016,2 and nearly 390,000 beneficiaries enrolled in HIP 2.0 in Indiana as of October, 2016.3 Indiana and Michigan both reported that they reached or exceeded enrollment targets shortly after implementation. Michigan and Indiana each transferred about 60,000 beneficiaries from their pre-ACA expansions to waiver coverage.4 Indiana also transferred nearly 70,000 non-expansion adults, including mandatory parents, 19 and 20 year olds, and those receiving Transitional Medicaid Assistance as they transition from welfare to work, to HIP 2.0 waiver coverage.5

Both states are experiencing some issues with the streamlined enrollment processes and renewals required by the ACA, which are not unique to their waivers. In Michigan, eligibility determinations can be processed within one day; however, individuals with more complex income situations, such as self-employed or seasonal workers, can experience waits. In Indiana, those who were enrolled in the state’s pre-ACA expansion seemed to transition smoothly to HIP 2.0, but new Medicaid applicants often appeared to experience a harder time with HIP 2.0 enrollment. Many Indiana beneficiaries, advocates, and enrollment assisters reported waiting 30 to 45 days to receive an eligibility determination, and some reported waits of 8 to 10 months. In both states, renewal notices were described as confusing, leading some eligible beneficiaries to lose coverage at renewal. To help retain eligible beneficiaries in coverage, Michigan is working to implement a passive renewal process, and Indiana began its passive renewal process in June, 2015.6

Beneficiaries were able to access needed health care services with their new Medicaid coverage, although challenges remain in certain areas. Many people who gained coverage in both states previously had been uninsured or had sporadic periods of coverage, leaving them without reliable access to primary care. Others previously had employer-sponsored coverage that they found unaffordable. Participants in our focus groups reported that obtaining Medicaid gave them peace of mind along with the ability to address health problems and access needed services, including primary, preventive and specialist care, mental health services, dental care, and prescription drugs. These observations are supported by Michigan state data showing that beneficiaries could get appointments and access care.7 There were some reports of beneficiaries in both states encountering challenges accessing certain services, including dental and behavioral health, similar to other states and at least partially attributed to pent-up demand by those who were previously uninsured. These access issues were reported as more pronounced in rural areas.

What is the Effect of Premiums in Michigan and Indiana?

Michigan

Although Michigan beneficiaries cannot be disenrolled from coverage or denied services for failure to pay premiums, some have had their state income tax refunds garnished. The state began charging premiums in October, 2014. From October, 2014 through July, 2016, about 38% of beneficiaries who owed premiums had paid them, resulting in collection of 31% of premiums owed (about $4.7 million out of $15.5 million).8 A Michigan state report to CMS noted that some beneficiaries calling the help line about their quarterly health account statements reported an inability to pay amounts owed.9 As of July, 2016, over 112,000 Michigan beneficiaries owed past due premiums or copayments, but only about 44,200 (less than 40%) of these were in “consistent failure to pay” status, subjecting them to garnishment.10 Beneficiaries reach “consistent failure to pay” status when they have not paid premiums and/or copayments within three consecutive months and owe at least $50 or when they have not paid at least half of their total premiums and copayments billed in the last year. The state recovered over $207,000 from about 2,150 tax refund intercepts and an additional $380 from six lottery winners from October 2014 through October 2016.11

Beneficiary advocates and enrollment assisters in Michigan noted that money order fees could sometimes equal or exceed the amount of premiums or copayments owed. Money orders are a common form of payment for those without bank accounts or credit cards. Of those making payments in Michigan, 71% are sending payments through the mail as of July 2016.12 Unlike Indiana, credit cards are not accepted as a form of payment in Michigan, although some beneficiary advocates preferred this policy as they saw it as preventing beneficiaries from accumulating consumer debt for health care costs that they could not afford. Other payment challenges reported by Michigan beneficiaries included lack of money or competing demands due to family caregiving responsibilities, joblessness, disability, and hospitalization.13

Indiana

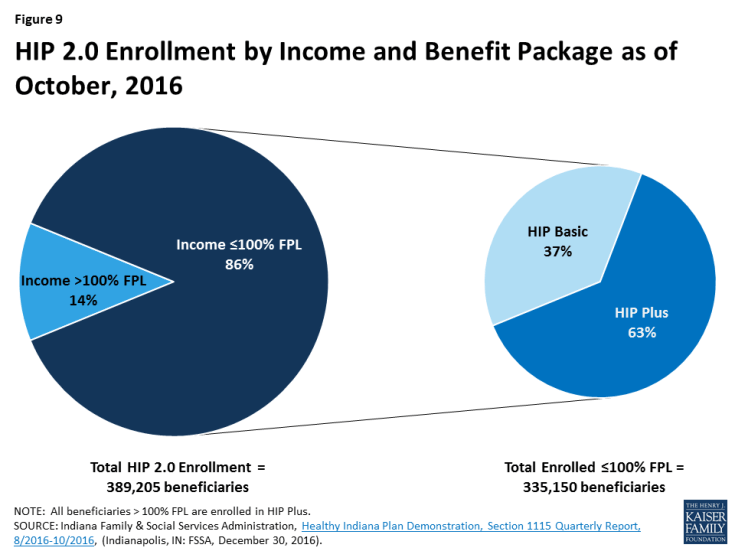

More than one-third (37%) of HIP 2.0 enrollees with incomes below poverty were not paying monthly premiums and therefore were enrolled in HIP Basic, the more limited benefit package with point-of-service copayments, as of October, 2016 (Figure 9). The consequences for failing to pay premiums vary by income in Indiana (Figure 2). The large majority (86%) of HIP 2.0 beneficiaries have incomes below poverty, and as of October, 2016, 63% of these beneficiaries were paying monthly premiums to enroll in HIP Plus, the expanded benefit package with dental and vision benefits and without point-of-service copayments.14

To date, a limited number of Indiana beneficiaries with income above poverty have been locked out of coverage for failure to pay monthly premiums. Approximately 14% of HIP 2.0 enrollees have income above poverty and therefore are subject to disenrollment and a 6-month coverage lock-out for failure to pay monthly premiums after a 60-day grace period. Between August and October, 2016, 4,621 HIP 2.0 beneficiaries were disenrolled and locked out of coverage for six months for failing to pay premiums.15 Based on the state’s enrollment data, this represents about 8.5% of beneficiaries with incomes above poverty.

“…You have to sit out for six months and pray you don’t get sick for six months.” – Indiana Medicaid Enrollee

However, individuals at all income levels in Indiana thought the lock-out applied to them. This belief was reported by beneficiaries in our focus groups as well as advocates and providers interviewed in Indiana, and may be due to the fact that under Indiana’s pre-ACA waiver (HIP 1.0), beneficiaries at all income levels were subject to disenrollment and a 12-month lock-out for failure to pay premiums.16

More than half of HIP 2.0 beneficiaries are assessed the flat minimum premium of $1.00 per month. Those with income from 0-5% FPL pay flat $1.00 monthly premiums to access HIP Plus benefits, instead of paying premiums at 2% of income. A large share of HIP 2.0 enrollees (51.5%) are reported by the state as having income between 0-5% FPL (up to about $50 per month for an individual in 2016) as of July, 2016.17 The high share of individuals in this group may be due to the administrative challenges of having to track and re-adjust premium amounts based on changes in income in a population that experiences frequent income fluctuations.

Data may be understating the number of HIP 2.0 beneficiaries receiving financial assistance to pay premiums. As of January 2016, 124 employers and 75 non-profit organization are recognized by the state as third parties making premium payments on behalf of 131 and 1,244 beneficiaries, respectively (less than 1% of beneficiaries).18 However, beneficiary advocates, health center staff, and enrollment assistors report that many more beneficiaries receive financial assistance than are reflected in the data and observed that family, friends, churches, and community-based organizations often are paying premiums for beneficiaries through informal arrangements that are not reflected in the state data. The state acknowledges that its data are limited to entities that have a formal arrangement with health plans as a third party payer. A 2015 state survey of HIP 2.0 beneficiaries found that 30% of those paying premiums to receive the enhanced HIP Plus benefit package reported receiving help with premiums as opposed to paying on their own.19 Among those who reported receiving help, 86% said they had help from a family member, and 25% said they had help from a friend (respondents could report more than one source of help).20

Indiana health centers, enrollment assisters, and beneficiary advocates reported that premiums presented affordability barriers, especially for those with the lowest income. These interviewees reported affordability issues especially for people with no or very low income and those who are homeless. Previous research has shown that premiums act as barriers to obtaining and maintaining coverage for those with low incomes.21

What is the Effect of Changes in the Effective Coverage Date in Indiana?

Under Indiana’s waiver, the requirement that individuals pay an initial premium before HIP Plus coverage is effective means that some people above poverty who are otherwise eligible for coverage do not enroll, and some applicants below poverty may experience waits of up to 60 days in effectuating coverage. Under HIP 2.0, there are two steps in the enrollment process that may postpone coverage (Figure 4). There is a period of time between the application and the conditional eligibility determination, and then an additional period from conditional eligibility to enrollment in coverage. Beneficiaries who have been determined otherwise eligible for HIP 2.0 but have not made their first premium payment are considered “conditionally eligible” for 60 days.

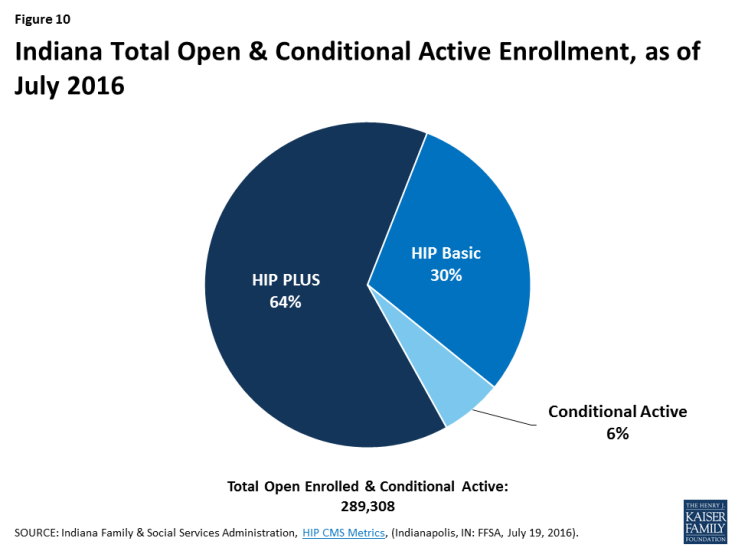

In July, 2016, 6% of those determined otherwise eligible for HIP 2.0 were considered conditionally eligible and need to pay their premium or for those at or below 100% FPL, wait for the 60-day payment period to expire to obtain coverage. The remaining individuals were enrolled in HIP Plus or HIP Basic coverage22 (Figure 10). The interim waiver evaluation prepared for the state noted that the number of conditionally eligible people may be as high as 30,000 during any given month23 and estimated that approximately two-thirds of conditionally eligible applicants eventually enroll in coverage by the end of the 60-day payment period,24 either by paying a premium to enroll, or for those from 0-100% FPL, defaulting to the Basic benefit package due to non-payment after 60 days, leaving approximately one-third eligible but unenrolled.

The “Fast Track” premium pre-payment option and expanded presumptive eligibility policies were adopted to safeguard against lengthy delays in effectuating coverage in Indiana, but beneficiaries, advocates, and enrollment assisters reported administrative complexity and confusion with these options. HIP 2.0 applicants could make the $10 Fast Track pre-payment by mail beginning in March 2015 (after they received an invoice from their selected health plan) and online by credit or debit card at the time of application beginning in June 2015.25 According to state data, 18% of total HIP 2.0 ever-enrolled members made Fast Track payments as of January 2016.26 However, some enrollment assisters and beneficiaries reported that Fast Track payments were lost or not showing up in the health plans’ IT systems leading to lags in effectuating coverage.27 Health plans do not process online Fast Track payments until the Medicaid eligibility determination is received from the state, and there have been issues with that information transfer process, generating confusion for providers, plans, and beneficiaries about coverage status. Some beneficiaries reported receiving Fast Track invoices from multiple health plans and difficulty having a payment they had made applied to their selected plan.

Between August and October, 2016, nearly 25,000 people were determined presumptively eligible for HIP 2.0,28 although some beneficiary advocates and providers reported that beneficiaries may encounter difficulty accessing care during that period. Beneficiary advocates and providers noted particular challenges with presumptively eligible beneficiaries attempting to fill prescriptions, which they attributed to IT system issues that can take 24 hours to transfer a beneficiary’s coverage status to health plans.29 To date, not all eligible providers are enrolled in the presumptive eligibility program, and not all enrolled providers are submitting presumptive eligibility applications.30 In addition, just under 42% of presumptively eligible beneficiaries were approved for full Medicaid between August and October 2016; while this rate has improved, it remains unclear whether the denials are due to procedural reasons, such as missing documentation to verify eligibility, or because the applicants are in fact ineligible.31 One study of a small sample of individuals suggests that procedural denials accounted for the large majority of those who did not move from presumptive eligibility to full coverage.32

Some HIP 2.0 beneficiaries are incurring medical bills that are eligible for Indiana’s prior claims reimbursement program. This program was implemented in August, 2015, as a condition of the waiver of three months of retroactive coverage. The prior claims payment program applies to mandatory parents, 19 and 20 year olds, and those who receive Transitional Medicaid Assistance who have incurred medical bills within the 90 days prior to their Medicaid application date. Indiana reported that over 10% of beneficiaries eligible for the prior claims payment program as of October, 2015, had incurred retroactive bills (628 out of 5,950 beneficiaries).33 Indiana proposed discontinuing the prior claims payment program, but CMS denied this request in July 2016, noting that 13.9% of beneficiaries eligible for the program incurred costs averaging $1,561 per person based on the latest data available.34 CMS will allow the state to discontinue the prior claims payment program when 5% of beneficiaries qualify.35

What are the Effects of Copayment Policies in Michigan and Indiana?

Beneficiaries in our focus groups did not understand the design of Michigan’s waiver that replaces point of service copayments with monthly payments based on past service use. Some beneficiaries in our focus groups reported that they preferred the predictability of having a set monthly payment amount, while others preferred paying the amount due at the point-of-service. The state implemented the monthly copayments in October 2014. Between October, 2014 and July, 2016, about 37% (about 180,000 out of 486,000) of those who owed co-payments had paid, resulting in collection of 36% (about $1.3 million out of $3.5 million) of co-payments owed.36 This may indicate the need for further beneficiary education about what the payments are and how they are determined.

Having a predictable and affordable monthly cost was seen by Indiana beneficiaries in our focus groups as preferable to incurring copayments for individual services, which can be burdensome for those who have multiple prescriptions or doctor visits in a month. For those with the lowest incomes who are assessed flat $1.00 monthly premiums and who have multiple medical appointments and/or prescriptions, it is often less expensive to pay the $12 annual premiums instead of point-of-service copayments in Indiana. Because point-of-service copayments are $4 for outpatient visits for non-preventive care and preferred prescription drugs and $8 for non-prescription drugs, a beneficiary with more than a couple of office visits and/or prescriptions can incur $12 or more in copayments in a month as opposed to paying $12 for an entire year of HIP Plus premiums at $1.00 per month. Advocates and enrollment assisters reported that beneficiaries appeared to be more motivated to pay monthly premiums based on the opportunity to avoid point-of-service copayments than by the ability to obtain additional benefits like vision and dental available in HIP Plus, although those services were cited as valued by beneficiaries as well.

Because it has not yet been fully implemented, it is too early to assess the impact of Indiana’s separate waiver authority to impose graduated copayments for non-emergency use of the ER. Indiana was approved to implement graduated ER copayments in February, 2016,37 and as of April, 2016, health plans were identifying beneficiaries to enroll in the ER copay demonstration.38 Between July and September 2016, about 23% of emergency room visits among all HIP 2.0 beneficiaries were deemed non-emergent by the health plans (nearly 33,000 out of just over 141,000 total ER visits).39 Even without the graduated ER copayments, Indiana reports that HIP beneficiaries historically have used the emergency room for non-emergent uses less often than traditional Medicaid beneficiaries in Indiana.40 At least one interviewee noted that there were some long-term benefits that could result from a non-emergent ER visit in terms of connecting people to coverage because some people who are eligible for HIP 2.0 enrolled in coverage via a presumptive eligibility determination in an emergency department.

What has been the effect of Health Accounts in Michigan and Indiana?

Beneficiaries, their advocates, and providers interviewed for this report in both states expressed confusion about the purpose and use of health accounts and the associated account statements. Beneficiaries described the account statements as long and complicated. Enrollment assisters and providers (especially community health centers) reported that beneficiaries had a lot of questions about their health accounts. This is consistent with findings from a state evaluation of Healthy Michigan beneficiaries showing that many did not understand how premiums and copayments are calculated, and most did not see any relationship between the account statement and their health-related behaviors including service costs.41 Michigan is revising its account statements based on stakeholder recommendations to use consistent terminology, define key terms such as health risk assessment and healthy behavior reward, refer to the dollar amount maximum instead of the 5% of income cap on out-of-pocket costs, use the term “discount” to describe healthy behavior incentives, and shorten and simplify language.42

In Indiana, beneficiaries were confused about the purpose of the POWER accounts, and many do not understand that their POWER account debit card was intended to be used at the point of service so that the provider could be reimbursed by the state. Some thought that the $2,500 deductible in the POWER account represented a cap on services, which could inhibit, rather than encourage the receipt of necessary preventive services.

Some health plan interviewees in both states reported administrative burdens associated with the health accounts. In Michigan, health plans noted high administrative costs to collect payments and differentiate payment requirements by beneficiary income. The plans also expressed interest in more flexibility around administering the accounts; for example, they would prefer to have a choice of vendor rather than being required to use the single vendor selected by the state. In addition, health plans would rather devote more resources and attention to achieving cost savings through providing care management to high utilizers instead of the state-required healthy behavior program.

In Indiana, the POWER account debit card was seen as an administrative burden by some provider interviewees. Not all providers have the technology to use it, and some that can may choose not to do so and instead use the traditional billing and reimbursement process.43 Although the POWER account debit card provides faster reimbursement, providers noted that those payments are at a discounted rate, and they would prefer to receive the full reimbursement rate even if that means waiting longer for payment. Additionally, providers explained that they may not know all of the services to be received and the associated billing codes before the appointment begins so they cannot correctly process the POWER account debit card at patient check-in.

“They send me a little credit card. . . I don’t know how that works.” – Indiana Medicaid Enrollee

“When I get those statements…I’m not really understanding what it’s all about… I mean you’re seeing all your services, but I really don’t understand the POWER account, what it’s all about and so on. It’s hard to understand.” – Indiana Medicaid Enrollee

What Effect Have Healthy Behavior Incentives had in Michigan and Indiana?

Few beneficiaries to date have completed the health risk assessment (HRA) process that is required for Michigan’s healthy behavior program, but those that do go on to select a healthy behavior to maintain or address to earn a reward. As of September, 2016, just over 16% of Healthy Michigan beneficiaries enrolled in a health plan for at least six months had completed an HRA.44 There is some concern that beneficiaries who are auto-assigned to a health plan may not be aware of or participate in the HRA process because most beneficiaries complete the initial HRA questions with the enrollment broker when they choose a plan. As of September 2016, 42% of Healthy Michigan beneficiaries were auto-assigned to a health plan.45 Between October and December 2015, none of the Healthy Michigan plans met or exceeded the state performance measure (20%) for timely completion of an HRA within 150 days of enrollment.46 However, a state survey of primary care providers found that 79% had completed at least one HRA with a patient, with most completing more than 10, and most providers thought that financial incentives for patients and practices had at least a little influence on HRA completion, although just over half thought that patients’ interest in addressing health risks had at least as much influence.47

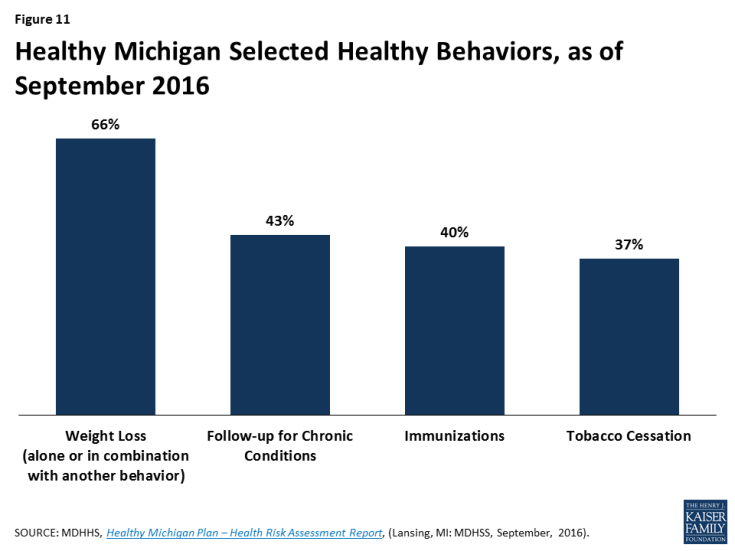

Of the over 121,000 beneficiaries who have been enrolled in a health plan for at least six months and completed an HRA in Michigan as of September, 2016, 99% agreed to address or maintain a healthy behavior, and 60% agreed to address more than one healthy behavior.48 The largest share of beneficiaries selecting a healthy behavior through September, 2016 chose weight loss (66%) either alone or in combination with another healthy behavior, followed by chronic condition follow-up (43%), immunizations (40%), and tobacco cessation (37%) (Figure 11). Compliance with healthy behavior incentives in Michigan will become more important beginning in April 2018, when failure to comply will result in enrollment in a Marketplace Qualified Health Plan with Medicaid premium assistance, instead of Medicaid managed care, for beneficiaries from 100-138% FPL under the terms of Michigan’s amended waiver.

“I mean… everybody wants to be healthy… and if you have some kind of incentive like oh, at the end… I’m getting $50, you know you can always use $50. So yeah, I think it’s a good incentive.” – Michigan Medicaid Enrollee

“I got a $50 gift card because I got my blood pressure down and my cholesterol down. And that… made everybody happy…but other than that I think it’s just about… going to see the doctor, getting your blood[work] done… It’s just like putting oil in your car, you know you’ve got to do something.” – Michigan Medicaid Enrollee

As of July, 2016, data were not yet available about health account rollover funds in Indiana. Beneficiaries need to be enrolled for a year before they are eligible to receive the HIP 2.0 healthy behavior reward.49 As a result, few Indiana beneficiaries, advocates, or providers in our focus groups and interviews were aware of how the HIP 2.0 healthy behavior incentive program works.

In both states it is unclear if a deferred benefit is an adequate incentive to participate in a healthy behavior program. As of July, 2016, nearly 86,000 Healthy Michigan beneficiaries have received gift cards, just over 39,000 have received a 50% reduction in premiums, and just under 23,000 have received a 50% reduction in copayments.50 A survey of Healthy Michigan beneficiaries found that nearly 40% “agreed that information about healthy behavior rewards helped them do something they might not have done otherwise.”51 In our focus groups, many participants had received gift cards, and one participant was aware of receiving a reduction in his cost-sharing amount. Beneficiaries noted that the more immediate receipt of the gift card, as opposed to a future reduction in cost-sharing amounts, was a greater incentive to complete the healthy behavior program requirements. While not offered by the state, some HIP 2.0 health plans offer gift cards as an incentive for complying with the plan’s own healthy behavior program, and beneficiaries in our focus groups reported liking and being motivated by those more immediate and tangible rewards. The future premium and cost-sharing reductions in Michigan and the roll-over of the POWER account funds in Indiana appeared to be less of an incentive compared to the gift card.

What effect have Other waiver Provisions had in Indiana?

“Medically frail” status in Indiana is viewed as an important beneficiary protection by beneficiary advocates and providers, but the current process may not identify all who qualify. As of July, 2016, just over 12% of beneficiaries enrolled in HIP 2.0 were identified as medically frail.52 There were some reports of lags in processing medical frailty determinations and concerns that the software does not recognize those who qualify based on substance use disorder because those services previously were not covered by Medicaid and therefore do not show up in claims history data. Beneficiary advocates and providers emphasized the importance of allowing providers to bring a beneficiary’s treatment history to the health plan’s attention, and at least one plan allows its caseworkers to identify beneficiaries as medically frail based on health issues that are not yet showing up in the claims history. Michigan currently does not vary program rules based on medical frailty status but will have to come up with a process to do so when its waiver changes for those from 100-138% FPL take effect in April, 2018.

While Indiana’s evaluation found that the availability of NEMT did not affect whether beneficiaries miss medical appointments due to a lack of transportation,53 community health centers and beneficiary advocates shared anecdotal concerns about negative impacts of Indiana’s NEMT waiver on access to care. The state’s evaluation asked beneficiaries if they had missed an appointment only if they first reported that they had scheduled an appointment; it did not ask whether beneficiaries had not scheduled a needed appointment due to a lack of transportation.54 The evaluation also found that those with income at or below 100% FPL were more likely to cite transportation as a reason for missing an appointment, compared to those with higher incomes.55 This also was true for those with higher risk scores, reflecting more severe health needs, compared to those with lower risk scores.56 Health centers and other community-based organizations reported helping beneficiaries with transportation to medical appointments by providing bus tokens and taxi vouchers.

To date, there has not been significant participation in the Gateway to Work referral program. As of January, 2016, 551 individuals had attended program orientations,57 and the state attributed low participation to the fact that the program is still relatively new. Beneficiary advocates attributed the low participation to the fact that many HIP 2.0 beneficiaries already are working (although many have jobs that do not offer health insurance), and others already participate in a similar program based on their receipt of food stamps or through the state vocational rehabilitation agency. Because the work referral program is voluntary, beneficiary advocates did not view it as a barrier to accessing Medicaid.

What Insights Have Emerged from Michigan and Indiana?

Five key insights emerge from an early look at Michigan and Indiana’s Medicaid expansion waivers.

- Medicaid expansion design, whether through traditional state plan authority or waivers, is highly dependent on the features of a state’s underlying Medicaid program. Michigan and Indiana both had implemented limited adult coverage expansions through waivers prior to the ACA, and those expansions along with the states’ pre-existing Medicaid delivery systems influenced the structure and design of their post-ACA waivers. Michigan incorporated its pre-existing capitated managed care delivery system into Healthy Michigan, while Indiana modified its pre-existing high deductible health account model under HIP 2.0. Regardless of whether a state adopts a traditional expansion or uses a waiver, expanding Medicaid can result in substantial reductions in the uninsured and increased access to needed health care.58

- Implementation of complex programs involves collaboration with a variety of stakeholders, sophisticated IT systems, and administrative costs. Both states’ waivers apply different rules based on differences in beneficiary income, health status, or other characteristics, which require time and resources to track. Challenges with information exchange between the state, health plans, and providers have created some confusion and delays in effectuating coverage in Indiana. Timely and accurate data about various beneficiary characteristics, such as income level, medical frailty, and healthy behavior status, will trigger different policies and delivery systems under the 2018 changes for those from 100-138% FPL in Michigan’s waiver, thus taking on increasing importance for the state and beneficiaries there.

- Premium costs and complex enrollment policies can deter eligible people from enrolling in coverage. Particularly for very low-income populations, even very low premiums may be unaffordable, and the cost of making payments (i.e., purchasing a money order) may add increased financial strain as well as a barrier. Policies in Indiana that tie the start of the coverage period to making a payment can be a further impediment, deterring some eligible people from enrolling. In addition, assessing the affordability of premiums in Indiana is challenging because it is difficult to track and adjust premium payment amounts for populations who experience frequent changes in income and to track how many individuals receive help with paying premiums.

- Health accounts can be confusing for beneficiaries. Beneficiaries in our focus groups as well as advocates and providers in both states did not demonstrate a clear understanding of the policies associated with these models. This feedback shows that these models are hard to understand even in Indiana, a state with long-standing experience with health accounts.

- Beneficiary and provider education and tangible incentives appear central to implementing healthy behavior incentive programs. Beneficiaries in both states indicated that gift cards that could be used immediately to purchase needed items were more appealing rewards than decreased cost-sharing amounts in the future, which is understandable, given the low incomes and precarious financial situation of many beneficiaries and the complicated formulas to calculate future cost-sharing reductions. To date, it is too early to determine if health accounts and healthy behavior incentives can change behavior, lead to more efficient use of health care services, and improve health outcomes, but these items hopefully will be assessed in the formal waiver evaluations.

At the time of our interviews for this study in summer 2016, both Michigan and Indiana were looking ahead to continued implementation of their waivers. Michigan reported plans to focus on its healthy behavior incentive program and simplify the health account statements under the waiver. At the same time, the state was working on issues that are related but not specific to the waiver, such as modernizing the eligibility determination system, streamlining the renewal process, overseeing health plan contracts, and integrating physical and behavioral health services. Michigan also was planning to prepare to implement the new waiver authorities approved by CMS that will affect beneficiaries between 100-138% FPL starting in April, 2018.

Indiana was planning additional outreach efforts targeted to eligible but uninsured residents. The state also planned to work on implementation of some waiver provisions, including the graduated copayments for non-emergency use of the ER and the POWER account roll-over healthy behavior rewards, that had not yet been fully implemented. In addition, enrollment assisters, health centers, and advocates pointed to needed improvements in the enrollment and renewal processes and noted the need for continued beneficiary education as well as IT system improvements related to the POWER accounts.

Looking ahead from a national perspective, it is not yet clear what role Section 1115 Medicaid expansion waivers will play as the new Administration and Congress move to repeal the ACA and debate possible broader changes to Medicaid financing such as a block grant or per capita cap.59 Repeal of the ACA would remove the statutory authority to cover expansion adults and the associated federal financing. However, given that some other states have expressed interest in pursuing Medicaid expansion waivers with components similar to those in Michigan and Indiana, it is important to understand the administrative framework and early implementation challenges and successes of the models being tested in Michigan and Indiana as more formal evaluations are conducted.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Michael Perry, Sean Dryden, and Naomi Mulligan Kolb with PerryUndem Research/Communication for their work managing the fieldwork logistics, conducting the interviews, and moderating the focus groups. We also extend our deep appreciation to all the participants for sharing their perspectives and experiences to inform this project.