A Primer on Medicare: Key Facts About the Medicare Program and the People it Covers

How do Medicare beneficiaries fare with respect to access to care?

The enactment of Medicare improved access to care for millions of elderly Americans.

Prior to the enactment of Medicare in 1965, less than half of all elderly people had insurance to help pay for hospital and other medical services.1 Many were unable to obtain health insurance either because they could not afford the premiums or because they were denied coverage based on their age or pre-existing health conditions. Medicare significantly improved access to care for elderly Americans and is now a vital source of financial and health security for nearly all Americans age 65 and older, as well as millions of people with permanent disabilities.

Beneficiaries generally enjoy broad access to physicians, hospitals, and other providers, and report relatively low rates of problems across a number of access measures. Yet, access problems are reported somewhat more frequently among certain subgroups, including younger adults with disabilities, low-income beneficiaries, and those in relatively poorer health.

- Usual source of care: The vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries (96%) report that they have a usual source of care for when they are sick or seeking medical advice.2 This key indicator of access to care is particularly important for Medicare beneficiaries because they tend to have more chronic conditions and medical needs than others. In fact, Medicare beneficiaries are more likely than younger adults with private insurance to report having a usual source of care.3

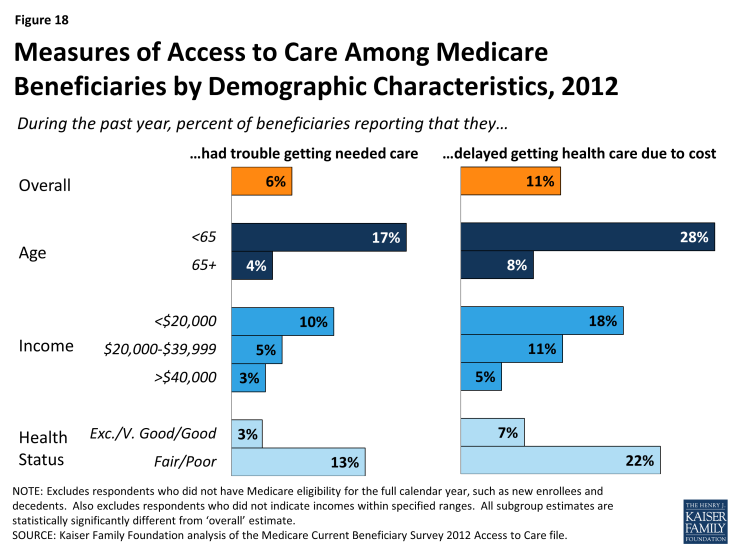

- Access to care: A relatively small share of Medicare beneficiaries (6%) report that they had trouble accessing needed medical care (Figure 18). A somewhat larger share (11%) report delaying care due to cost burdens. Certain subgroups of Medicare beneficiaries report access problems more frequently than others, particularly those who often need more health care services. For instance, Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 (most of whom qualify for Medicare because of a long-term disability) report experiencing trouble accessing care at more than four times the rate of their older counterparts (17% versus 4%). The share of Medicare beneficiaries who report that they delayed care due to cost is three times as high for people with incomes below $20,000 compared to those with income of $40,000 or more. Also, Medicare beneficiaries who report that they are in fair or poor health are considerably more likely to encounter problems getting needed care or delaying care due to cost, relative to those reporting comparatively better health.

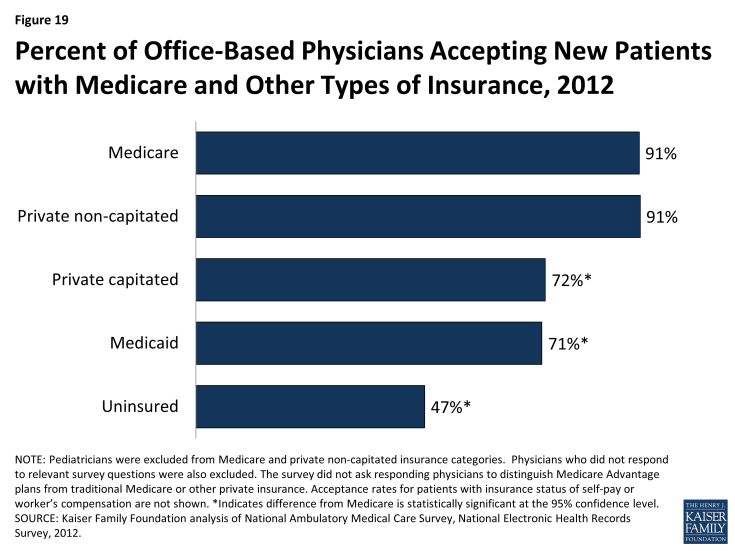

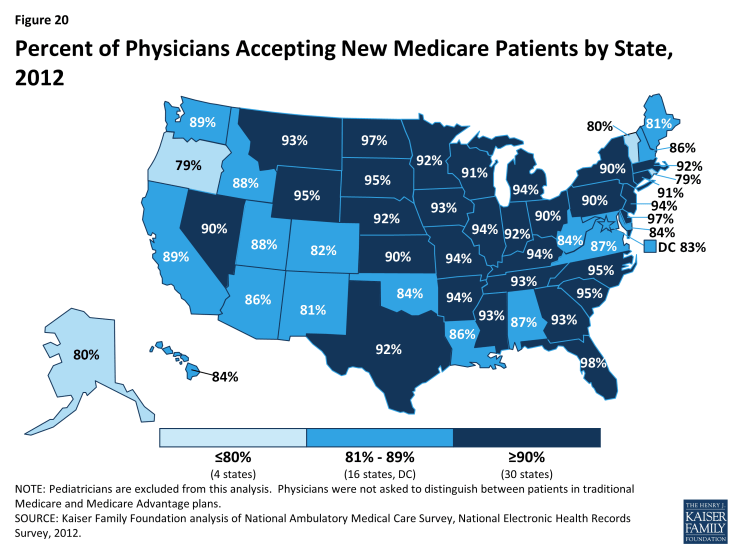

- Physician acceptance of new Medicare patients: The majority of office-based physicians (91%) report that they accept new Medicare patients into their practice (Figure 19).4 This acceptance rate for new Medicare patients is the same as the rate for new patients with private non-capitated insurance, such as a preferred provider organization, and is higher than for new patients with private capitated insurance (72%), Medicaid (71%), or no insurance (47%). Across the country, there is some variation in acceptance rates, but in each state, the majority of physicians accept new Medicare patients (Figure 20).

- Finding a new physician: Medicare seniors are as likely to report problems finding a new physician as people aged 50 to 64 with private insurance.5 Nonetheless, for both groups of individuals, problems finding a new doctor are more frequently reported when looking for a primary care physician compared with a specialist. Among the small share of Medicare seniors (7%) who said that they looked for a new primary care physician in 2013, 28 percent reported a problem finding one—equating to about 2 percent of all seniors in Medicare.

- High physician participation rates mean predictable expenses for most Medicare patients: The vast majority of physicians and other health professionals (96%) who bill Medicare are “participating providers,” which means that they agree to accept Medicare’s fee-schedule rates and will not “balance bill” their Medicare patients (charge higher fees for Medicare-covered services). As a result, most beneficiaries encounter predictable expenses when seeing their physician. A small share of physicians (less than 4%) who bill Medicare do not have these agreements and may balance bill up to a specified maximum for Medicare covered services.

- A very small share of physicians “opt out” of Medicare: Less than 1 percent of physicians has elected to “opt out” of Medicare and instead contract privately with all of their Medicare patients. These opt-out providers may charge Medicare patients any fee they choose. Psychiatrists represent a disproportionate share (42%) of these physicians, which raises concerns about access to psychiatrists for beneficiaries who cannot afford high out-of-pocket costs.