2012 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health

Section 3: Views on U.S. Global Health Spending

Despite General Support For Current Level Of U.S. Spending On Global Health, Skepticism About Progress And Concerns About Economy Make Americans Wary Of Increasing Spending

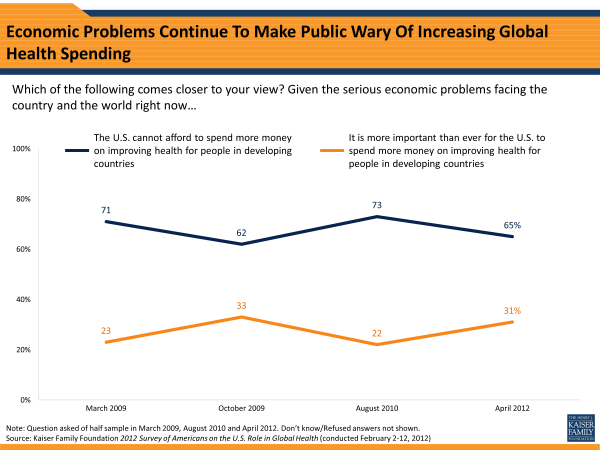

While two-thirds of Americans say that the current level of U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries is too little or about right, economic concerns continue to make the public wary of the idea of increasing spending abroad. In 2012, nearly two-thirds (65 percent) say that given the serious economic problems facing the country and the world, the U.S. cannot afford to spend more money on health in developing countries, while three in ten feel the current economic conditions make it more important than ever for the U.S. to increase such spending.

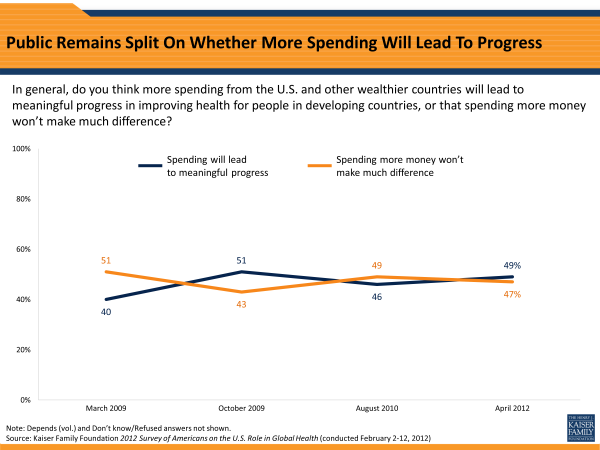

As previous Kaiser surveys have also shown, the public’s reluctance to increase U.S. spending on global health efforts may be related to the fact that Americans are divided as to whether more spending from the U.S. and other wealthier countries will lead to meaningful progress in improving health in developing countries (49 percent) or won’t make much difference (47 percent).

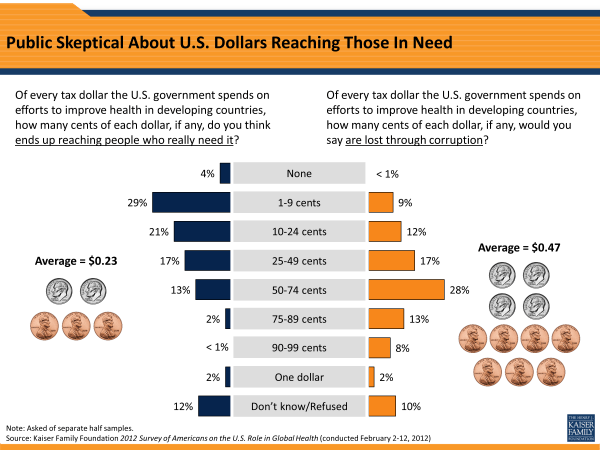

This skepticism about the ability of additional spending to lead to progress ties in with another key finding from the survey: many Americans do not believe that U.S. money is getting to where it needs to be on the ground, and most perceive that a large share of this money is being lost through corruption. On average, Americans believe just 23 cents of every tax dollar the U.S. spends on improving health in developing countries ends up reaching people who really need it. The public believes twice as much money—47 cents of every tax dollar spent on these efforts—is lost through corruption.

Trends In Attitudes Toward U.S. Spending On Health In Developing Countries

On several measures of attitudes toward U.S. spending on health in developing countries, Americans’ views appear to have gotten somewhat more generous since the summer of 2010. For example, 32 percent now say the U.S. spends too little in this area, up 9 percentage points since 2010, and 31 percent now say the economic crisis makes it more important than ever for the U.S. to spend more on health in developing countries, also up 9 percentage points. These marks do not represent new high points in support for increased spending, however, but rather a return to the levels seen in the fall of 2009.

| Figure 16: Trends in Views on U.S. Global Health Spending | |||||

| Mar 2009 | Oct 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | ||

| Amount U.S. spends to improve health in developing countries is… | |||||

| …too much | 23% | 25% | 28% | 21% | |

| …about right | 39 | 32 | 42 | 34 | |

| …too little | 26 | 34 | 23 | 32 | |

| U.S. should spend its tax dollars on improving health… | |||||

| …in the U.S. only | n/a | n/a | 48 | 42 | |

| …in the U.S. and globally | n/a | n/a | 49 | 55 | |

| Given the serious economic conditions facing the country and world… | |||||

| …U.S. cannot afford to spend more on health in developing countries | 71 | 62 | 73 | 65 | |

| …it is more important than ever for the U.S. to spend more | 23 | 33 | 22 | 31 | |

Democrats More Likely Than Republicans To Place Top Priority On Health Issues; Still, Majorities Across Parties Think Current Level Of U.S. Global Health Spending Is Too Low Or About Right

While many questions of U.S. policy, particularly those that involve spending, tend to be polarizing and characterized by large differences by political party, partisan differences in opinion on U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries appear to be more modest. For example, while those who identify as Republicans are somewhat more likely to favor a decrease in current levels of spending and Democrats are more likely to favor an increase, a healthy majority of Democrats (74 percent), independents (66 percent), and Republicans (59 percent) perceive current levels of spending to be too little or about right.

Framing the question in terms of U.S. tax dollars produces somewhat more of a division, with a majority of Democrats (60 percent) and independents (57 percent) saying tax dollars should be spent on improving health in the U.S. and globally, while Republicans are more split between spending tax dollars on improving health in the U.S. only (48 percent) or at home and abroad (47 percent). Still, these partisan differences are much smaller than the differences that surveys tend to measure on many other policy issues, such as recent debates about the domestic health reform law.

Some underlying partisan differences in perceptions of the impact of U.S. spending on health in developing countries may help explain the small but measurable differences in support for spending. For example, while a majority (57 percent) of Democrats believe that more spending from the U.S. and other wealthier countries will lead to meaningful progress in improving health, a similar share of Republicans (58 percent) feel that more spending won’t make much difference. And across the board, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to feel that spending money on health in developing countries brings benefits to the U.S., including protecting the health of Americans, improving the U.S. image in the world, helping U.S. national security, and helping the U.S. economy by creating new markets for U.S. goods.

When asked about various priorities for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries, majorities across all parties say each of the 13 priorities asked about in the survey is important. However, there are certain areas that Democrats are more likely than Republicans to rank as “top priorities.” The biggest partisan differences are in the share placing a top priority on reducing hunger and malnutrition (76 percent of Democrats vs. 39 percent of Republicans), improving access to family planning and reproductive health services (40 percent vs. 16 percent), preventing and treating heart disease and other chronic diseases (35 percent vs. 12 percent), and improving access to clean water (76 percent vs. 58 percent).

| Figure 17: Views on U.S. Global Health Spending by Political Party ID | |||||

| Total | Dems | Inds | Reps | D-R | |

| Amount U.S. spends to improve health in developing countries is… | |||||

| …too much | 21% | 15% | 22% | 28% | -13 |

| …about right | 34 | 34 | 32 | 40 | -6 |

| …too little | 32 | 40 | 34 | 19 | +21 |

| TOTAL TOO LITTLE OR ABOUT RIGHT | 66 | 74 | 66 | 59 | +15 |

| U.S. should spend its tax dollars on improving health… | |||||

| …in the U.S. only | 42 | 38 | 42 | 48 | -10 |

| …in the U.S. and globally | 55 | 60 | 57 | 47 | +13 |

| More spending from the U.S. and other countries… | |||||

| …will lead to meaningful progress in improving health | 49 | 57 | 50 | 37 | +20 |

| …won’t make much difference | 47 | 38 | 48 | 58 | -20 |

| Percent who say spending money on health in developing countries… | |||||

| Helps protect the health of Americans | 70 | 82 | 66 | 62 | +20 |

| Helps the U.S. economy | 42 | 50 | 42 | 35 | +15 |

| Helps U.S. national security | 45 | 51 | 43 | 39 | +12 |

| Helps improve the U.S. image in the world | 58 | 63 | 59 | 52 | +11 |

| Percent who say each of the following should be “one of the top priorities” for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries: | |||||

| Reducing hunger and malnutrition | 58 | 76 | 54 | 39 | +37 |

| Improving access to family planning and reproductive health services | 33 | 40 | 35 | 16 | +24 |

| Preventing and treating heart disease and other chronic diseases | 26 | 35 | 26 | 12 | +23 |

| Improving access to clean water | 67 | 76 | 65 | 58 | +18 |

| Efforts to improve training and expand the supply of medical professionals | 40 | 47 | 40 | 31 | +16 |

| Preventing and treating malaria | 34 | 39 | 34 | 23 | +16 |

| Eradicating polio | 28 | 34 | 26 | 18 | +16 |

| Children’s health, including vaccinations | 58 | 64 | 59 | 50 | +14 |

| Preventing and treating HIV/AIDS | 43 | 47 | 45 | 37 | +10 |

| Efforts to reduce the number of women who die during childbirth | 37 | 38 | 38 | 31 | +7 |

| Building and improving hospitals and other health care facilities | 39 | 40 | 39 | 34 | +6 |

| Combating global pandemic diseases like swine flu | 38 | 44 | 36 | 39 | +5 |

| Preventing and treating tuberculosis | 32 | 31 | 31 | 30 | +1 |

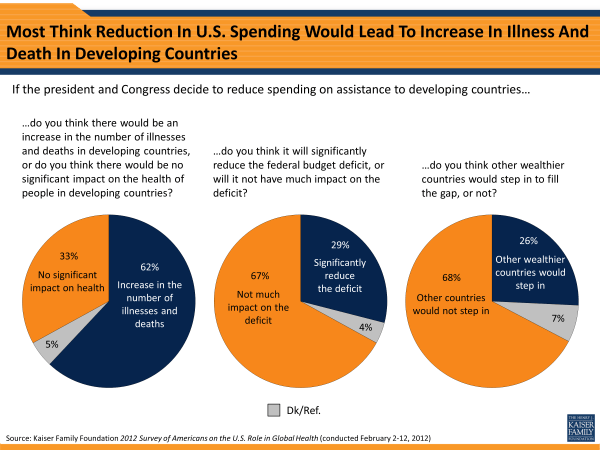

Most Think A Decrease In U.S. Funding Would Result In More Illness And Death, And Few Think Others Would Step In To Fill Gap

At the same time that they are skeptical about more spending leading to progress, a majority of the public (62 percent) agrees that if the president and Congress decide to reduce spending on assistance to developing countries, there would be an increase in the number of illnesses and deaths, while a third (33 percent) think such a decrease would not have a significant impact on the health of people in these countries. Further, two-thirds (67 percent) feel that a decrease in spending on assistance to developing countries would not have much impact on the federal budget deficit, while three in ten (29 percent) believe the deficit would be significantly reduced.

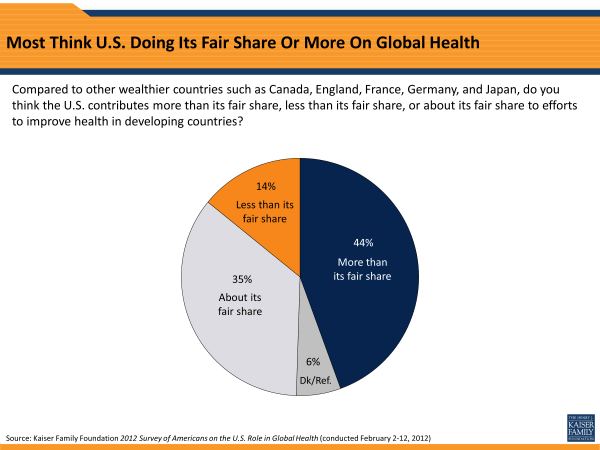

Only about a quarter (26 percent) of the public believes that if the U.S. were to decrease spending on assistance to developing countries, other wealthier countries would step in to fill the gap. In fact, the largest share of Americans—44 percent—believe that compared to other wealthier countries, the U.S. already contributes more than its fair share to efforts to improve health in developing countries. Another third (35 percent) believe the U.S. share is about right, while just 14 percent feel the U.S. currently contributes less than its fair share. 1

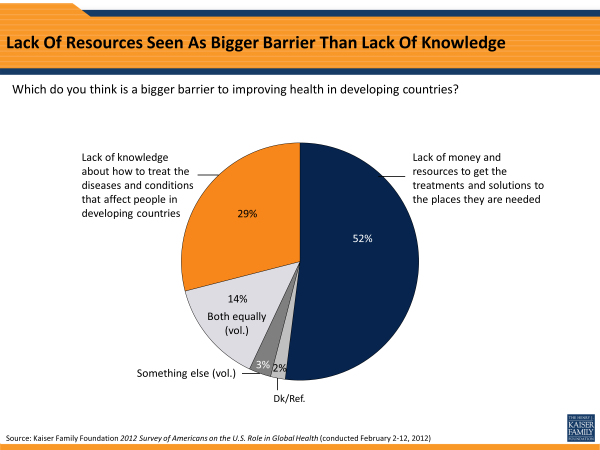

More generally, Americans seem to recognize that lack of resources is a major roadblock to making progress on health. When asked which is the bigger barrier to improving health in developing countries, more than half (52 percent) choose lack of money and resources, while three in ten (29 percent) choose lack of knowledge about how to treat the diseases and conditions affecting people in these countries.